A typical working day for Myrtle Broome

Author: Susan Biddle.

This post describes a typical working day for Myrtle Broome and the methods she and Amice Calverley used to record the relief scenes and inscriptions of the Temple of Seti I at Abydos.

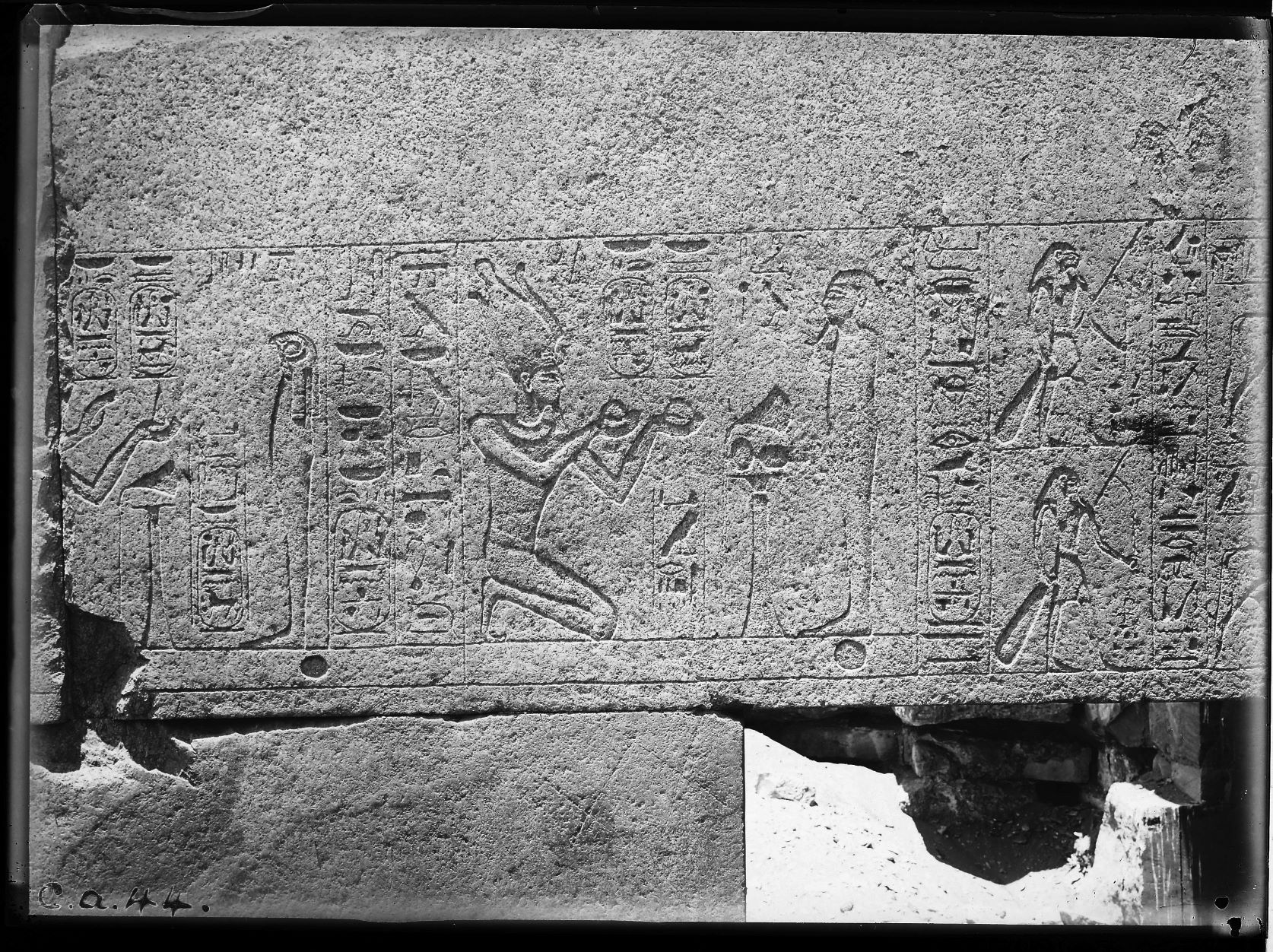

In 1925–1926 the Egypt Exploration Society commissioned the professional architectural photographer Herbert Felton to photograph the relief scenes of the Temple of Seti I at Abydos.

AB.NEG.25.044

Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society

The following year Raymond Faulkner started to record the inscriptions. It was soon clear that the photographs needed to be supplemented with line-plates and Amice Calverley was recruited in 1928 to copy scenes by hand. The quality of her drawings contrasted with the purely schematic record of the inscriptions, and when John D. Rockefeller Jr. offered funding, including for coloured plates, the project was transformed into a magnificent record of both scenes and inscriptions. The original estimate the project anticipated ten years’ work and a cost (for the expeditions and a “thorough, scholarly and artistic” publication) of US$105,000 –approximately US$1.7 million in 2022!

Amice Calverley explained the approach in the introduction to the first volume of The Temple of King Sethos I at Abydos: “The photographs prepared by Mr Felton during the first two seasons’ work have naturally influenced the technique finally adopted by ourselves. In those early negatives the problem of lighting under difficult conditions and in constricted spaces had not been dealt with adequately, and much of the delicate detail of the sculptures was lost. It was mainly for this reason that pencil drawings were decided upon. The photographs were first enlarged to scale, and were then traced by hand over a specially constructed tracing-board, which consisted of a box furnished with a ground-glass top and containing powerful electric lamps. […] The tracings were subsequently taken to Egypt, where the drawings were finished in front of the originals. Finally experts were called in to check the inscriptions. […] In order to exhibit the character and fine quality of the reliefs, the line-drawings have been supplemented by photographs and coloured plates”.

This short summary does not do justice to the meticulous attention to detail which their work required. Myrtle told her father: “I have never seen so much delicate detail in any place before, it needs most accurate & careful copying. Each tiny hieroglyph is in itself a perfect picture, the wee ducks all have their wing feathers marked & the owls have their faces most carefully carved & the men & gods are wonderfully represented & their bead necklaces & pleated linen robes drive one to distraction. & as for the wigs & head-dresses!!”

Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society

Some of the details required very fine brushes – several of Myrtle’s letters include requests for her father to buy her sable water colour brushes of the smallest sizes, and miniature brushes with shorter than usual hairs. She explained that “the detail we have to put in is so tiny that one needs the wee’st brushes made. & one needs some with the usual length hair & some short”. Soon after the brushes arrived, she reported that she was “very glad of the tiny ones especially, they are useful for painting the little beads in the necklaces”.

They also made scale drawings of the reliefs on site in the temple, before filling in the details by tracing direct from the negatives of photographs of the reliefs. Sometimes they used a “camera lucida” as an alternative to photography. George Nuttall, Professor of Biology at Cambridge, had visited Amice at Abydos in 1929 and recommended this device to her. He explained that “the camera lucida is mounted on an extensible metal tubular shaft which can be inclined at any angle and is fixed basally by a screw attachment to table or drawing board. By placing various lenses in front of the prism according to working distance and whether enlargement or reduction is desired, the work is greatly facilitated and more accurate. It is really very simple and efficient”.

Calverley MSS I.7, letter 3, p. 2

Griffith Institute Archive

The daily working routine was similar throughout Myrtle’s eight seasons at Abydos, but varied according to the temperature. At the beginning and end of each season, when it could be well over 100° F (= c. 40° C) in the shade by mid-day, Myrtle, Amice, and any other European members of the team would get up about 5.15 a.m. and work in the Temple of Seti I from 6.15 a.m. until mid-day, with a drink and biscuits at 10 a.m. since they had only a light breakfast. They returned to the house for lunch and rested during the early afternoon when it was too hot to work as “the heat makes the pencils smudgy”. They would then do another hour and a half’s work later in the afternoon before sunset. They sometimes worked at night relying on electric light provided by the generator; Myrtle explained to her mother that “we have a projector which throws the image from the negative onto a drawing board, we trace the outline & so get the whole picture correctly spaced out very quickly”. On these occasions supper was brought to them at the temple. Myrtle described one evening when they “sat among the mighty columns and [ate] omelettes, bread & butter & chocolate mould, our white-robed servants waiting on us like attendant priests. It was a weird scene”. On another occasion when they worked late, they picnicked on cold chicken pie and fruit salad on the roof of the temple “as there was a cool breeze & a glorious slender new moon, pale green in colour, floating in an opal sky”.

By mid-December it was cool enough to be able to work in the early afternoon too. They could start a little later in the morning, and their lunch was brought to them in the temple. In the early seasons, after lunch they went for a short walk or sun-bathed on a convenient sand hill. By the third season, they were more adventurous, and played ping-pong in the temple on two large drawing boards. Myrtle explained that this “takes the stiffness out of our backs after bending over our drawing boards, & is great fun”, but acknowledged that it was “rather a strange way of worshipping the gods”.

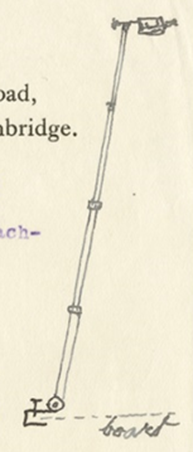

By January the sun did not reach the temple until the afternoon and a north wind could make the mornings particularly cold. In December 1935 Myrtle deliberately arranged her work so that at the coldest part of the year she was working on a painting which required her to curl herself up in a little box-like space which they called the “dog kennel”. There was room to sit but not to stand, and elbow room was very limited, but it was “a nice snug place out of the wind”. When recording the reliefs high on the walls, she worked perched on a scaffold “which feels very wobbly but has a good wide platform [with] room enough for a trestle, a chair & wooden box”. In hot weather Myrtle would keep a bowl of water on her scaffold in which to cool her hands.

Photograph by Myrtle Broome

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

It was not until 1934 that Myrtle took out from England an easel so that she could work standing up. The easel turned out to have multiple uses – she used it as a coat hanger, a hat rack, and a towel rail, and also draped cloths over it to keep the sun off her back.

The men carried the drawing boards and materials between the house and temple, set up and moved the scaffolds, and guarded the equipment from the tourist visitors to the temple, for whom the guards had little time. On Fridays the servants and guards had an hour off to go to the mosque. During Ramadan, the men’s hours were adjusted to as to give them either the morning or afternoon off, since they were tired and sleepy.

The essential facilities were available at the temple: “a little tent [was] fixed up with a sand closet & wash bowl”; this was known to the servants and guards as the “house of good behaviour”, which Myrtle thought “the most poetic description of an unromantic necessity” she had ever heard. In the last season, bees built a nest over the door and “buzz round our heads when we go in & out & we have to be careful we do not sit on one”.

At the end of the working day, they had tea either at the temple or on their return to the house. Once back in the house they had hot baths before their evening meal. Myrtle told her mother “a large copper bowl big enough to sit or kneel in is placed in [my] room, also a large can of hot water and ditto of cold, so [I am] able to get a really good sponge down”. She washed her underclothes at the same time – they were dry before bedtime. She found a little eau de Cologne on her sponge in her bath restorative: “it makes you feel so fresh & helps to take the tired feeling away. It is a little luxury one appreciates very much out here”.

Several evenings during the week, Amice and Myrtle held a “doctor’s parade” for the local villagers; most ailments were “quickly dealt with, a bottle of Lysol water & a handful of Epsom Salts”, but others were more serious. Amice became known to the Egyptian women as the “Mother of Purges”.

Tuesday was the local market day, and Myrtle and Amice’s day off, when they enjoyed a lie-in with breakfast at 8 a.m. They still had to fit in various chores, such as washing and mending – the heavy washing was done by local Egyptian women, but they washed their more delicate garments themselves. Most of the servants and guards were paid weekly, and this was done on Tuesdays. Myrtle usually wrote her letters home on Tuesdays and Fridays, and she might also do preparatory work for further drawings. Tuesday was also their day for shopping in the market, visiting friends, day-trips, picnics in the desert with visitors, and sketching for pleasure.

Sources:

Letters 32, 33, 34, 35A, 36, 37, 38, 39, 47, 53, 55A, 57, 58, 75, 79, 81, 101, 103, 105, 110, 119, 130, 134, 150, 152, 173, 211, 260, 298, 306, 317, 325, 357, 359, 387, 393, 396.

Calverley MSS I.7 (Nuttall Correspondence), Letter 3.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Myrtle’s letters, and on the Calverley collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Egypt Exploration Society, for copies of their photographs of the 1925–1926 season at Abydos and paintings of the relief from the Temple of Seti I, and for access to their Amice Calverley Archive

- the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, for the online copy of The Temple of King Sethos I at Abydos

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for copies of photographs from their Myrtle Broome Collection