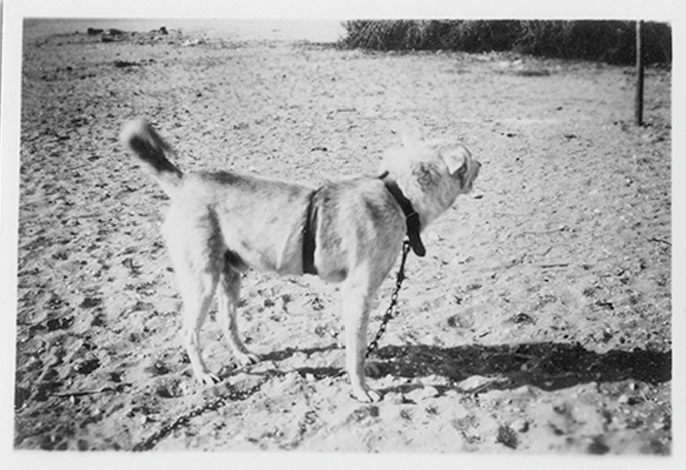

Animals – 1: Camp dogs – 1

Author: Susan Biddle.

Myrtle Broome’s interest in animals, and love of dogs in particular, is clear in many of her letters. This post is one of a series looking at the animals she encountered, and is the first of two focusing on the dogs which guarded the dig house and the Temple of Seti I at Abydos.

Over the eight seasons when Myrtle Broome worked at Abydos, the dig house was guarded by three dogs. The first was called Wip-wat. He guarded the house against intruders, both human and animal. In January 1930 Myrtle told her mother that in recent nights they had been “rather disturbed by jackals, they are getting very hungry & bold. They can smell our chickens & prowl round the house: of course our dog barks frantically”.

Wip-wat was always pleased to see them when they arrived each year. At the start of the 1930–1931 season, both Myrtle and Amice reported that Wip-wat looked “fat & well”. The following year Myrtle told her mother: “our dog was delighted to see us & greeted us with much bouncing & loud wuff wuffs. He is in splendid condition”. Similarly, when they arrived in camp in November 1932, she reported that “our dog waved his tail & pranced with delight”.

Wip-wat had to be kept chained at the house, otherwise he would run back to the village, but was let free when possible. He often accompanied the team on their outings, which he enjoyed as much as they did. In January 1931 Myrtle went for a camel ride north into the desert one evening and told her mother: “our dog came with me & had a gorgeous time chasing a wolf that was on its way to the cultivation for its evening meal. He didn’t succeed in catching it, but came back looking very pleased with himself”. The following month, Amice and Myrtle took two visitors – geologists surveying the Nile valley for data for a pre-Neolithic history – for a picnic up one of the nearby wadis with a sand slope. Myrtle rode a camel; the rest of the party including the servants all rode donkeys, and they were again accompanied by Wip-wat. When they got to the sand dunes at the base of the wadi cliff, Wip-wat “went mad with excitement, he’d never been on fine sand like that before, he raced about, rolled in it & tried to bite it, he galloped up the steep sides of the dunes, charged through the crest in a flurry of sand & scampered down the other side”. The party, together with the dog, climbed up to the high desert and along to the top of the sand slope. Here Myrtle told her mother that Wip-wat “had an extra burst of exuberance, & as we were standing on the top ride of the slope he suddenly charged me from behind, I sat down with a flop right on top of him”. Dog-lover that she was, she was unfazed by the experience, and simply laughed.

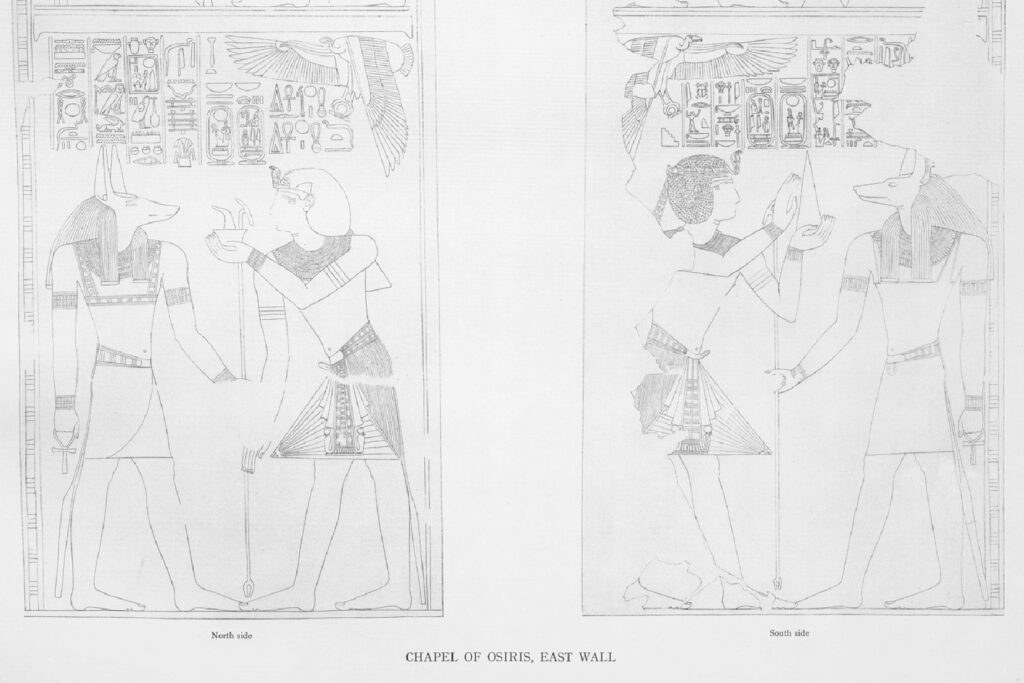

Myrtle often commented how well-behaved Wip-wat was. At the wadi picnic in February 1931 he “sat with us & behaved beautifully, sitting expectant & accepting nicely when he was offered a piece, although he simply dithered with excitement when he thought a bit was coming his way”. In April that year Wip-wat joined them at work in the Temple of Seti I one day and “behaved very well”; Myrtle told her mother that they “were able to compare him with his namesake the dog-headed god on the walls. They are very much alike”.

Details from The Temple of King Sethos I at Abydos, vol. I (1933), plate 3

Courtesy of the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures of the University of Chicago

They took good care of the dog, treating his various ailments with prompt attention. In December 1932 Myrtle reported back home: “our dog has hurt his foot & it feels hard & swollen, so he is being poulticed. He is as good as gold & does not make a bit of fuss when the scalding hot bread goes on”. They tied up the dressing in one of Myrtle’s old stockings, just as they did with their human patients; she indicated that Wip-wat “looks so pathetic sitting with his paw held up”.

However, in November 1933, Myrtle had very sad news for her mother: “our darling dog has been poisoned, the police were throwing poisoned meat in the market place, & he happened to be loose & had run to see us in the temple & then joined the other dogs & got a piece. This indiscriminate poisoning of dogs is awful”.

Captioned by Myrtle: “Anticipation. Iswid has a tit-bit & Wip-wat waits his turn”.

Myrtle Broome (1931)

Letter 123

© Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

Wip-wat was not the only dog guarding the site – the temple guards were accompanied by their own dogs who were an essential part of the security arrangements. In December 1929 the dog belonging to one of the guards, Mahomed, was similarly poisoned by accident and died before they could do anything for it. Myrtle told her parents: “the poor old man nearly wept, he said he would not have been more distressed if it had been one of his children … we are very sad for Mahomed. It was a well trained watch dog, no-one but its master or any of his family dared to touch it”. The loss of the dog raised practical problems as it had “guarded the engine room every night. Now since the dog is dead & a trained dog is not easy to get, the old man will have to sleep near the engine room, & we have to provide him with a shelter. It is rather a problem. He must be near enough to be roused if anyone attempted to enter, but not too near for his little fire to be a danger on account of the petrol”.

Myrtle ensured that the ailments of the temple guards’ dogs were treated. In February 1935 she noticed that a particularly fierce dog belonging to one of the guards was limping, with a swollen front paw. When the guard explained that his dog had been bitten by another dog, she told him to heat water and apply hot cloths, which he did. Myrtle told her mother that the dog must have connected the relief this treatment gave him with Myrtle, “for next morning I stopped to see how it was & the man said it was much better. I bent down to look, & I am bothered if the dog didn’t sit down and offer me his paw. It was much better & he could put it to the ground. The next day I took him a piece of bread & patted him after he had eaten it, & now he will let me touch him any time, if his master is present or not. All the men are very surprised”. Later that month she reported that she always gave the dog a bit of bread when she passed him, so the dog “has now decided that all Europeans are friendly to dogs & waves his tail to all of us, guests included. Before, he allowed us to pass without barking, but he looked us over with a calculating eye & if we had a guest with us he became a raging fury. His master is very amused”. Two months later she updated her mother, writing that “the guard’s dog looks for his piece of bread every day when I return from work. It has got to be quite a ceremony, I think old Mahommed sometimes invites some of his pals along to see it”. The practice continued the following season; in November 1935 Myrtle told her mother that “the guard’s dog was wild with delight when he saw me again. He leapt up at me & put his paws on my shoulders. Fortunately I had a piece of nice new bread ready for him. Old Mahomed is very proud of him; when he sees me coming, he says to the dog, ‘Rise up oh my brother, the lady comes’”. In December she offered the dog a treat along with his usual bit of bread: a piece of cheese from her lunch that had got very hard; she told her mother: “I am quite sure it was a new flavour for him, he looked so surprised when he got his teeth into it, but licked up all the crumbs out of my hand so I suppose he approved”.

By the following year the guard was training two new young dogs who also had to share in the bread ceremony. In November 1936 Myrtle explained to her mother that these young dogs “know us & do not bark when we pass but they are too snappy to feed by hand. We toss them their portion, but the gentle red dog always accepts his bit most daintily”. In early December, when they went to feed the guard’s dogs as usual on their way home at the end of the day, they “found a fourth dog or rather bitch waiting with them, so we had to give her a share”. At this point Mrytle felt enough was enough, telling her mother that “we shall have to stipulate that we cannot have any more pensioners, otherwise I do not know where it will end. We shall find the dogs of [the guard’s] relations & friends tied up alongside his in a long row stretching from the house to the temple”. However, in February 1937, this guard was pensioned off “as he was long past the age that the government permits a guard to remain in service”, so he had returned to his family home in the village together with his dogs. Myrtle told her mother that they missed the dogs very much, but the guard “brings them to visit us every Sunday and Thursday, these being the days we have meat for lunch & we can save nice scraps for them. They go mad with excitement when they see us & nearly pull the old man over in their eagerness to greet us”. The new guard was a relation of one of their servants and was accompanied by his own dog, which Myrtle said was “quite friendly to us. He was very shy at first but is used to us going by every day now”. However the dog was “very fond of his master & howls dismally if he is not there”.

Myrtle Broome (date unknown)

© Bushey Museum & Art Gallery

Sources:

Letters: 46, 53, 96, 105, 117, 123, 133, 146, 195, 201, 243, 320, 324, 347, 358, 383, 387, 395.

Gardiner MSS 43 – Calverley Correspondence, Letter 141.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection and the Abydos Enterprise correspondence within the Gardiner collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for Myrtle Broome’s painting

- the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures of the University of Chicago, for the online copy of The Temple of King Sethos I at Abydos