Animals – 4: Snakes

Author: Susan Biddle.

This post is one of a series looking at the animals that Myrtle Broome encountered during her eight seasons working in Egypt (1929–1937). This instalment focuses on snakes.

Snakes rarely intruded into the dig house or the Temple of Seti I at Abydos. In January 1930 Myrtle reassured her mother that “it is quite safe to wear [rubber] shoes now as all the snakes have gone to sleep in their holes for the winter. (I have only seen one since I have been here)”. She and Amice Calverley were cautious of snakes during the hot weather, Myrtle telling her mother in November 1936: “we have not been for any walks yet, it is too hot during day light, & as we have seen snake tracks in the sand we do not care to venture out after sunset. Later when the cool winds come the snakes will all hole up for the winter”.

The snakes that did appear near the dig house or in the temple were swiftly despatched, particularly the poisonous horned vipers or Cerastes. In May 1930, Myrtle explained to her mother that Ahmud Waled, one of the Egyptian servants, had “killed a cerastes (horned viper) outside our house, it caused quite an excitement”. In November the following year, Myrtle reported that “we had great excitements in the temple yesterday, one of the guards came in with a snake that he had killed in the road outside, it was the sort called the horned viper (it occurs often in the hieroglyphs) & was over a yard long, had a broad head with two little horns above its wicked-looking eyes, & a long thickish body ending in a thin tail … It is a very poisonous variety & it is exceptional for one to come out of its hole this time of the year. It was fortunate the guard saw it in time to kill it. Of course he was full of pride at his achievement”. Reporting the same incident to Alan H. Gardiner, editor of The Temple of King Sethos I at Abydos on which Amice and Myrtle were working, Amice told him that this snake was the largest she had ever seen, “over 37 inches long … & with the most horrible head on it!”. Amice dried the snake’s skin and told Gardiner: “you may be glad that you weren’t here during the process for truly it was a b—- proceeding!”.

Letter 147, page 1

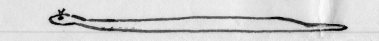

The following January, Myrtle told her mother: “one of our old guards caught another horned viper … & brought it to us alive in his handkerchief. It was only a small one about 20 inches long, its fangs were as large as cat’s teeth & set right in front of its mouth, & it could open its jaws at an angle like this [sketch]. It was very brave of the old man to catch it alive as it is the most venomous of all snakes. Of course in the winter they are very torpid & cannot move quickly”.

Letter 161, page 3

Myrtle’s sketch showing how wide the horned viper could open its jaws, and its fangs

Letter 161, page 3

The camp was designed to deter the entry of snakes. After the horned viper was found outside the house in May 1930, Myrtle reported back home that Nannie, the Syrian housekeeper, “has had the gateway into the garden walled up so we have to step over it to come in & out. This is to prevent snakes getting into the house as they are evidently waking up from their winter sleep”. In early November 1935 a snake did venture inside the walls, Myrtle telling her mother that the first night the Sudanese guard were at the camp, “they found a viper in their room curled up in the sand”. She immediately ordered a brick floor to be laid in the room, explaining to her mother that “snakes will seldom enter where they cannot make a hole to hide in”.

Two weeks later she reported that “Mahmud killed another horned viper beside our wood pile. It was about 18 inches long”. As Myrtle told her mother, this snake inadvertently caused some alarm. Undeterred by her earlier experience of drying a snake skin, Amice wanted to skin this one too, and “its corpse was laid out on a stone slab just by our entrance”, where “it gave Sheikh Jed el-Karim [Myrtle’s Arabic teacher] such a fright when he came for the lesson yesterday”.

Myrtle was not unappreciative of the beauty of snakes. In November 1929 she told her mother that the servants had killed “a lovely little snake outside the house”, which she and Amice had “put … in a bottle of spirits & hope to get … identified some day”. When the guard brought the horned viper alive in his handkerchief to show them in January 1932, Myrtle and Amice were very relieved when he killed it quickly with a heavy block of limestone, but she nonetheless told her mother: “it was wonderful to see the thing alive & how it moved & how it tried to attack when he put it on the sand”.

Myrtle also made several visits to the tomb of Sheikh Ali, who she explained to her mother was “a very holy man & a member of the sect of snake charmers”. The Sheikh’s descendants were also snake charmers and “have a large walled enclosure by the Tomb where the snakes live”. Myrtle told her mother that “if a mother wishes her son to be immune from snake bite, she takes him to the Sheikh in charge of the place (who is great grandson of the original Sheikh Ali) & he places a big snake round the boy’s neck, & writes him a charm, & after that no snake will ever harm him. Also, if a snake is found in any person’s house, he sends for the Sheikh, who comes & takes the snake away, he calls to it & the snake will follow him”.

Myrtle made her first trip to Sheikh Ali in March1931. On that occasion the Sheikh wrote her a special charm to protect her from snakes, for which she paid him 10 P.T. Unfortunately, she could not see the snakes as the man in charge of them was in Girga and had taken the key with him. However the Sheikh undertook to bring a big snake to Arabah for her to see in a few days’ time. Later that week the Sheikh appeared as promised “with a big cobra, he had it wrapped up in a shawl. He put it down & it reared & put its hood up. It realised it was in a strange place & it slithered up to its master as though seeking protection. He picked it up & I took a photo of him holding it against him, & then another photo of it on the ground with its hood up”.

Myrtle visited Sheikh Ali again in March 1932, when she took him his photograph and some flowers from the garden as an offering for the shrine, and paid him P.T. 20 for a charm which she gave to Sardic’s new gamoose (water buffalo) “to protect it from snakes, scorpions, vipers etc.”. She explained to her mother that people made pilgrimages to the shrine from all over Egypt, and those who could afford it brought an offering, typically food which the Sheikh then used to provide meals for the very poor who came to him. In March 1936 she described to her father another visit to “my old friend Sheikh Ali of the tribe of snake charmers”, this time accompanied by all the servants and some of their relations, all of whom “asked the sheikh to write them charms, some for themselves, or families or even for their animals. Singab [who hired his camel to Myrtle for these trips] of course had one for his lady camel & our water carrier asked for one for his buffalo to ensure a continual flow of milk”.

They occasionally encountered snakes when trekking in the desert. In March 1931 Myrtle spent a day’s holiday riding a camel into the desert, escorted by the head servant Sardic and two more of the men, Ahmud and Mahommed. After a picnic lunch, Myrtle, Sardic, and Ahmud explored one of the wadis to the south of Abydos. The top of the wadi became very steep and narrow, and Myrtle was searching for footholds when “Sardic became very interested in a small cave just beside [a crack leading up the rock]. He said to me, ‘it would be best to go back now, for this is the house of a very big fierce snake. There was his track on the sand of the floor of the cave, so I thought it wisest to follow Sardic’s advice”.

When she made a three-day trek into the desert during her holiday in April 1934, Myrtle originally intended to camp up one of the wadis. However she rethought her plan when the sheikh of a nearby village advised her that “there were a great many scorpions & snakes among the rocks there”. Instead she took up the sheikh’s invitation to sleep on a divan from the village meeting room on the raised veranda of the meeting house, and was plagued instead only by other “visitors” despite substituting her own blankets and cushion for the original cushions and coverings. The following day Myrtle met three members of the Sudanese camel patrol who, when consulted, “advised [her] as to a good camping place free from scorpions & snakes”. Camping that night in the desert, she was untroubled by any animal visitors.

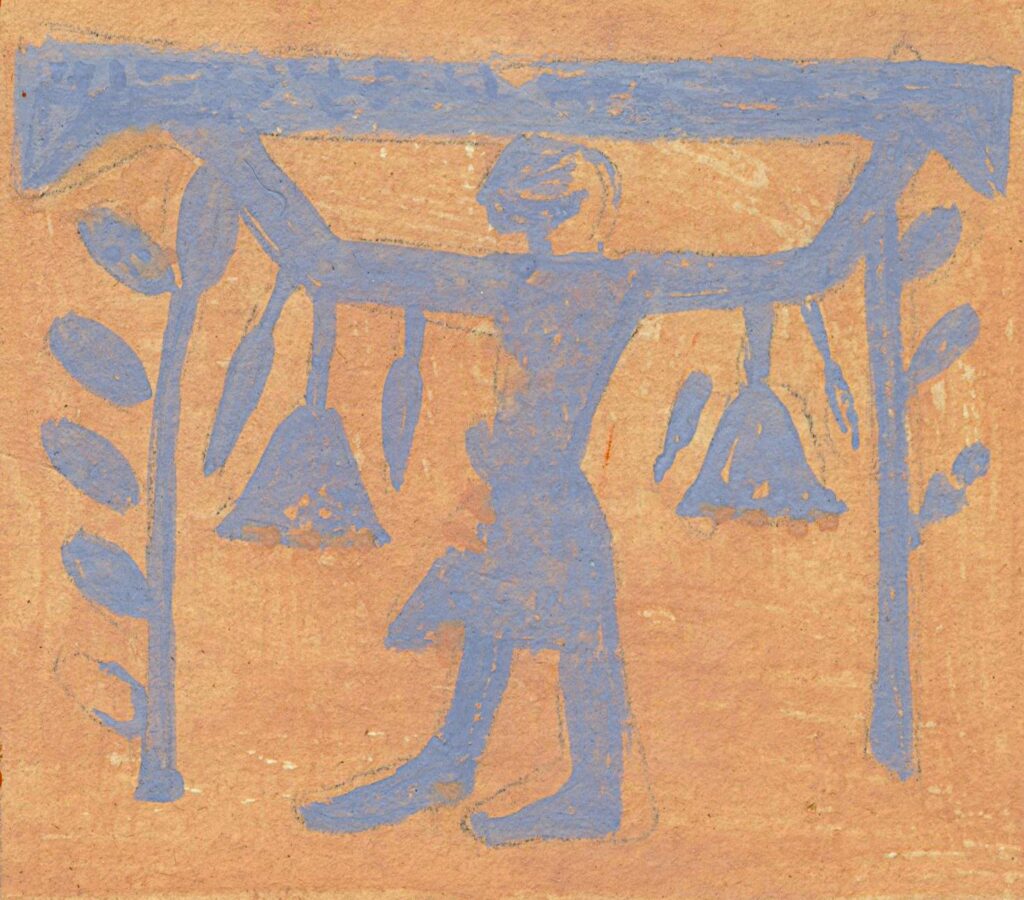

Myrtle and Amice also drew and painted numerous snakes in the course of recording the reliefs in the Temple of Seti I at Abydos. In December 1930, Amice told Alan H. Gardiner: “I’ve been seeing so many snakes of late that I almost pray for St Antony – the tops of shrines are no joke when it comes to painting”. Amice was presumably referring to the legend that, when Franciscan friars built a new church at Siolim in Goa in 1600, a huge serpent terrified the masons and friars so much they almost abandoned the project in favour of another site. However the Franciscan friars prayed to St Anthony and placed his statue in the church, and the following day the snake was found dead, hanging from a cord in the saint’s hand: an event commemorated in a statue in the church showing St Anthony holding a serpent tied with a cord.

Clen Madeira, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

On 1 January 1933 Amice similarly told Gardiner that there was so much detail in the paintings in the small rooms of the temple that progress was slow, complaining that “the shrine in my picture had no less than 117 snakes which is most unkind to the poor painter!”.

(Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society)

Sources:

Letters: 42, 53, 86, 122, 125, 147, 161, 178, 284, 285, 347, 351, 374, 383.

Gardiner MSS 43 – Calverley Correspondence, Letters 131, 140.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection and the Abydos Enterprise correspondence within the Gardiner collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Egypt Exploration Society, for the painting of the relief from the Temple of Seti I