Learning Arabic – 4

Author: Susan Biddle.

This is one of a series about Myrtle Broome’s experience of learning Arabic. This post is the second of two looking at Sheikh Sarbit, the first of her two Arabic teachers. It focusses on her dealings with him and his family outside lessons, as well as the practical application of the Arabic he had taught her.

When Myrtle returned to Abydos for her fourth season in December 1932, she found that Sheikh Sarbit had married over the summer. His bride remained in his home village near Sohag, 40 miles from Abydos, since there was no suitable house for her in Beni Monsur where the schoolteacher lodged with the headman of the village.

In January 1933 Myrtle bought a box of sweets for the schoolmaster to take back to his wife for the feast at the end of Ramadan, but found that this caused unexpected embarrassment. She explained to her mother that she gave the sweets to him at the last lesson before he returned home, “& could not think why he looked very confused & didn’t say a word, I wondered if I could have made a mistake in pronouncing the word for wife & said something awful instead. I felt very embarrassed & tried to carry on the conversation by asking what time he started his journey & then he recovered & talked as usual & when he went he took the box of sweets & said ‘I am very grateful all the same’”. All was revealed later that evening when Sardic, the head servant, told Myrtle that the schoolmaster had said to him: “I do hope the lady is not offended with me, I was so stupid when she gave me the present for my wife but I was so shy I could not say a word”. Myrtle and Nannie, the housekeeper, were much amused “at the idea of the poor schoolmaster being overcome with shyness at the mention of his wife. He evidently is not at all used to being married yet”. Myrtle hoped that “he will be more broken in to matrimony by the end of the fortnight’s holiday”.

Myrtle, with her Arts and Crafts background, was very interested in the local weaving traditions, and in January 1934 she and Amice visited silk and cotton weavers in Girga.

Photograph by Myrtle Broome (1929 or 1934?)

Bushey Museum & Art Gallery

Myrtle knew that Sheikh Sarbit came from a district famous for its weavers and showed him her purchases, whereupon he told her that “in Akhmim [near his village] they use all pure silk & do still finer work than the Girga weavers”. She intended to ask him if he would come with Amice and her to Akhmim to show them the weaving.

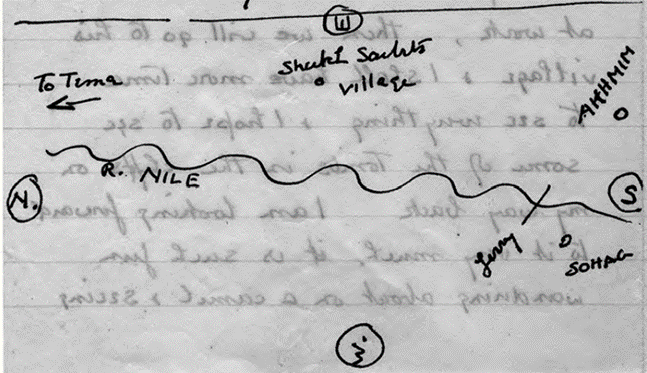

The proposed visit took place the following month; Amice and Myrtle went by car to Akhmim, where they were met by Sheikh Sarbit who took them to see both cotton and silk weavers. They were delighted with the silk weaver’s work and thought his prices very reasonable, so placed lots of orders for a total of about £10. Sheikh Sarbit wrote out their order on the back of one of Myrtle’s visiting cards (obtained the previous year for the more mundane purpose of giving to Cairo bank managers) and she was “sure [he] was bursting with pride at having introduced such customers to his friend the weaver”. Amice then returned to Sohag to lunch with their friends the Oultons, as she had hurt her leg and did not feel up to a long donkey ride. Myrtle, however, set off on “a superb donkey, jet black with a green plush saddle”, with Sheikh Sarbit, his uncle, and a few hangers-on, for the schoolteacher’s home village 9 or 10 miles away.

Letter 282, page 4

When she arrived at his house, she “rode through his front door & dismounted in a sort of courtyard” before being “escorted up a flight of brick stairs to the first floor where the harem reception room was, here the young wife was presented to me. She was lovely, more like a Spanish girl than the usual Arab type. … She has the perfect oval face with a lovely curve from the cheek to the chin & fine dark eyes & a light coffee coloured complexion & tiny hands & feet. She is as usual her husband’s first cousin”. Myrtle thought she was probably about 17 or 18, and that she and the schoolteacher “make a charming couple. She was dressed in blue flowered silk with a head veil of embroidered silk in a pale shade of blue … She had gold coins to weight her long plaits of hair & a fine gold necklace of coins & gold bracelets & heavy silver anklets – the jewellery was her husband’s bridal gift to her”. Other members of the family were also presented to her, and she enjoyed a light lunch of fruit, nuts, and a plate of cakes made by Sheikh Sarbit’s wife.

Following that visit, Myrtle asked Sheikh Sarbit for the names of his various relatives whom she had met and wrote these down so she could send them greetings when she wrote to him from England. However when she asked his wife’s name, “he would not let me write it among his male relations, it had to be written on a separate piece of paper, & he explained that it was for me specially”. Myrtle was intrigued by this, but sensitive to Sheikh Sarbit’s feelings, telling her mother: “It is curious that the name should be so guarded, as the wife was unveiled before the male members of his family, but of course no unrelated man was present. Possibly the idea is that as anyone can read men’s names it is not polite for a woman’s name to be written among them in case a strange man read it. It is a little difficult to understand their explanations & I do not like to ask questions as Sheikh Sarbit is so very shy & he might find it embarrassing to answer”.

Sadly, a month later, in March 1934, Myrtle was “bereft of my nice schoolmaster. Sheikh Sarbit has been removed to a village near his home”. She was “very glad for his sake, as he was very lonely & unhappy so far away from his own people, but of course I miss him very much”. They remained in touch, at least for a while.

In April 1934 Myrtle spent a short holiday in Sohag, staying with the British sub-consular agent Charles Oulton and his wife and using their home as a base for day trips by camel. She planned to visit a cave with hieroglyphs two days’ camel ride from Sheikh Sarbit’s village and wrote to him asking if he could recommend a guide and whether she could hire two camels from his village for baggage (she would hire riding camels in Baliana). When she arrived in Sohag, “who should be waiting at the station to meet me but Sheikh Sarbit – (wearing the scarf I had given him). He had come all the way from el-Sawamah Sharq [his home village] to say ‘how do you do’ & ask if he could serve me in any way”. They arranged that he would meet her in Akhmim the following day so she could visit the silk weavers again, and then visit his village. She followed this programme and was again received in the harem by Sheikh Sarbit’s wife, mother, and other ladies of the family. After lunch, which she ate “in solitary state with the Sheikh’s wife to wait on me”, Sheikh Sarbit’s wife “showed me all her dresses & ornaments & took a great interest in all I was wearing”. Several other members of the family also came to greet Myrtle, and she took the opportunity to acquire some local information to assist her in planning a longer desert trek. Sheikh Sarbit and his uncle then accompanied her when she visited some tombs in the nearby cliffs, about an hour’s camel ride away. It was “a great scramble” up to the tombs, “rougher than the last lap up Snowden”, and she “was absolutely blown by the time we reached the tombs in spite of frequent rests on the way up”. Sheikh Sarbit was usually rather reserved, though he was often amused by the stories she wrote him in Arabic: “he does not think it is polite to indulge in a good laugh in front of me”, though he was sometimes overcome by helpless giggles. Consequently, when they scrambled down from the tombs, she was amused “to see Sheikh Sarbit shed his dignity & go bounding down like a small boy released from school”.

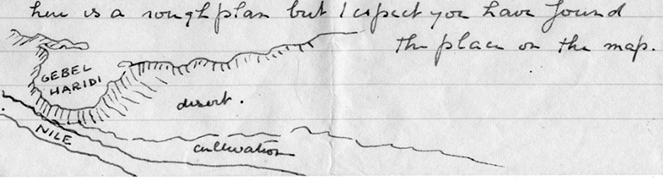

A few days later she made a longer trip, again by camel, from Sohag to Gebel Haridi, which she found “very beautiful, an immense rock of weathered limestone”. Here she visited a famous sheikh’s tomb “up a wild rock-strewn wady, it was a long climb, but the scenery was magnificent”, and some ancient stone quarries which “went a long way back into the cliff & from the entrance one could look right across the width of Egypt to the fringe of the Western Desert”. The following day she returned “along the strip of desert that lies between the cliffs of the high desert & the cultivation”.

When she stopped for a picnic lunch, the sheikh of a local village offered her coffee “which was delicious” and provided “a regular banquet” for the men accompanying her. She told her mother that she hoped she “made all the proper replies to the ceremonious greetings & compliments”.

That night Myrtle, Sardic, and her Sudanese guard camped in the desert within sight of el-Sawamah Sharq, Sheikh Sarbit’s home village. Soon after she had retired to sleep, Myrtle was roused by Sardic with the news that “Sheikh Sarbit had ridden out to enquire if there was anything he could do for me. I sent a message to thank him & say I had everything I required & that I was too tired to see him that night, but hoped to say goodbye to him before I departed in the morning”. Sheikh Sarbit had brought with him “a lovely old Persian rug, some cushions & a quilt” and, while Myrtle went back to sleep, the men sat together chatting into the night, the Sudanese guard being “a lovely sight rolled up in a pale blue quilt”. As Myrtle observed, “even in the desert one cannot quite escape Arab hospitality”.

The following morning, as Myrtle finished washing, “Sheikh Sarbit & his uncle arrived on donkeys to wish me good morning – there was nothing else I could do but receive them in my nightie & dressing gown!! But fortunately I had on one of my nice long pink silk nighties & my Cretan dressing gown, so probably my visitors thought I was wearing my robes of state in their honour”. While the visitors greeted the men, she seized the opportunity to dress and “then joined the party round the camp fire & sat on a cushion on the Persian rug & eatsic two freshly boiled eggs that Sheikh Sarbit had brought specially for my breakfast”. After breakfast they went to visit a Roman-era Coptic church nearby, where she “had to take coffee with the priest & there was a regular sort of reception in the little courtyard & many invitations to visit other places in the neighbourhood”. She was grateful that “Sheikh Sarbit protected me from too much importunity on the part of aspiring hosts”. Later that day, she finally made it to the tomb caves decorated with reliefs, inscriptions, and paintings, which had been the original objective of her trip. Myrtle told her mother that she had very much enjoyed her trek; “it was very good for me to have to depend entirely on my knowledge of Arabic for three whole days, for in that time I did not meet a single person who could speak anything else & I really got on quite well”. She had much to be grateful for to Sheikh Sarbit.

At his request, Myrtle continued to write to Sheikh Sarbit during the summer, although another schoolteacher, Sheikh Jed el Karim, took over her lessons. The last mention of Sheikh Sarbit in her letters is in November 1934, when Myrtle told her mother that his replacement as headmaster had been found by the omdah [village headman] to be “not very satisfactory” – clearly it was not only Myrtle who missed him.

Sources:

Letters: 197, 205, 207, 209, 264, 270, 272, 275, 278, 282, 283, 284, 285, 287, 296.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for Myrtle Broome’s photographs