Learning Arabic – 5

Author: Susan Biddle.

This is one of a series about Myrtle Broome’s experience of learning Arabic. This post is the first of two looking at Sheikh Jed el Karim, the second of her Arabic teachers, and the prestige associated with being her teacher.

Myrtle first met her second teacher, Sheikh Jed el Karim, at the start of the fourth season in December 1932, when her first teacher Sheikh Sarbit “made a state call with his two under masters”, one of whom was Sheikh Jed el Karim. At Christmas he came with Sheikh Sarbit to the “fantasia” staged by the Egyptian members of the Abydos team for the entertainment of the whole team, their Christmas guests, and the villagers. Both sheikhs came dressed “in their best robes”, and were honoured by being given chairs, unlike the other Egyptians who squatted on the sand. Both teachers also attended Myrtle’s Arabic lesson on 2 January 1933, to wish her a Happy New Year, and the rivalry between the two teachers quickly became apparent. Myrtle told her mother that Sheikh Jed el Karim “sat on the divan while Sheikh Sarbit and I wrestled with dictation. Fortunately I did rather well & my efforts were passed over to the other master, it was a whole page of an exercise book closely written & he settled down to a careful examination of it”. A little later Myrtle’s reading aloud was interrupted when Sheikh Jed el Karim “announced with great glee that he had discovered a spelling mistake that Sheikh Sarbit had passed over – & then of course there was a solemn correcting of it. I don’t know exactly what Sheikh Sarbit said to the other teacher but I noticed he took the book away from him”.

At the start of the following season, Sheikh Jed el Karim took over Myrtle’s lessons while Sheikh Sarbit was ill in hospital. Myrtle explained back home that she “got on very well with Sheikh Jed el Karim & he was delighted to have the opportunity”; he was very interested in the story she was writing for her Arabic exercise “& reads it out with great gusto”. A week later, Myrtle told her mother that her new teacher was “on his mettle” to prove his ability; he was “the one that found a mistake that Sheikh Sarbit had passed over, so he pounces at once if I make the slightest slip”. When she made “a very silly mistake” putting a masculine verb with a feminine noun, “he was horrified & it was amusing to see his efforts to reprove in a respectful manner”.

As soon as he was out of hospital, Sheikh Sarbit resumed the lessons, although Sheikh Jed el Karim was “very reluctant to relinquish his duties”. Both sheikhs attended the lessons on several occasions, but Sheikh Sarbit was quick to reassert his authority over his under-master, being “very critical over some of the corrections” made by Sheikh Jed el Karim.

Although both teachers appreciated the humour in many of the stories Myrtle translated into Arabic, Sheikh Jed el Karim seems to have been less serious and quicker to see a joke than Sheikh Sarbit. In December 1933 Myrtle wrote a story based on an incident in George Bernard Shaw’s play Caesar and Cleopatra. In Shaw’s version, the queen asks her harpist slave’s music teacher to teach her to play the harp, so she could entertain Caesar. In a reversal of the usual system of punishing the pupil, Cleopatra tells the teacher that if she makes any mistakes after two weeks’ lessons, she will have him beaten. The play had been produced by the Old Vic company at the Old Vic and Sadler’s Wells Theater in September-October 1932 – perhaps Myrtle and her parents had seen one of these performances the previous year, with Peggy Ashcroft playing Cleopatra and Harold Chapin as the musician. They certainly attended other plays by George Bernard Shaw; in February 1930 Myrtle had been glad to know both parents had enjoyed their trip to London to see Shaw’s new play – this was perhaps The Apple Cart, which was first performed in 1929 and was on at what was then the Queen’s Theatre in Shaftsbury Avenue from September 1929 until May 1930.

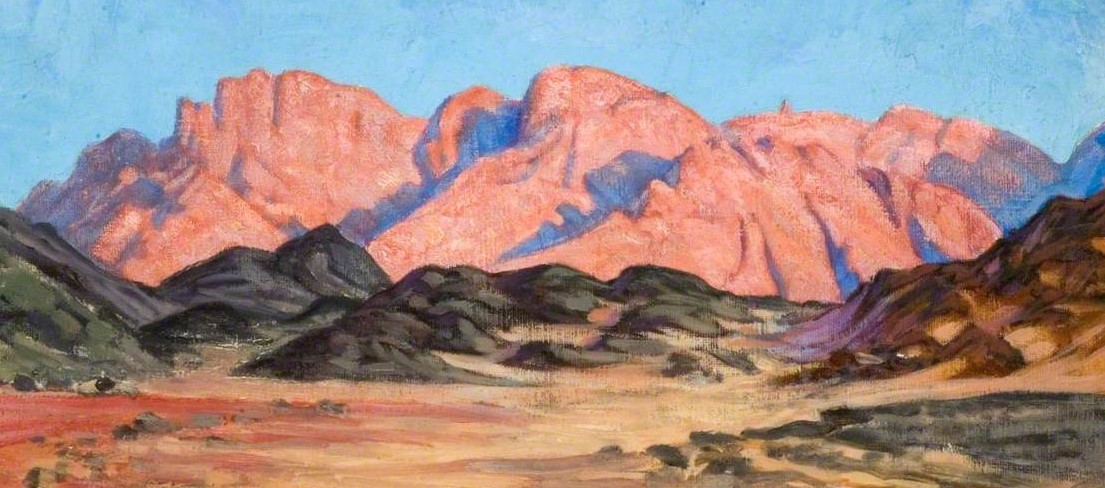

Myrtle Broome

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Myrtle “made this up into quite a good Arabic story with a few frills & when the two school masters turned up as usual, I produced it. Sheikh Sarbit set to work to correct it, reading it out sentence by sentence. By & by I saw a very puzzled look come over his face & he went back & read it over again to see if he had mistaken anything. Sheikh Jed el Karim who was listening saw the humour of it at once & burst out laughing. Then Sheikh Sarbit also saw the point of the story & laughed too. They were very tickled at the idea of the master being beaten for the pupils’ faults”.

That month Sheikh Jed el Karim brought a party of masters from a neighbouring village to see the team’s work at the Temple of Seti I, and was impressed by Myrtle’s diligence when he discovered her studying her Arabic lesson book during her lunch break. Myrtle thought that “he was very puffed up with pride at having a friendly conversation with me in front of all the visiting masters”.

Myrtle was careful to treat both sheikhs fairly. Each year Mrs Broome sent Myrtle several calendars from England to decorate the dig-house, and at New Year 1934 Myrtle gave one to each sheikh. She told her mother: “they know the English numbers & I carefully filled in the names of the months in Arabic for them & explained the meaning of the word Greetings on the covers. I chose the two that were alike in design, only one was blue & silver & the other was red & silver”.

In January 1934 the local school closed for the Ramadan holiday and Sheikh Sarbit returned to his own village for ten days. Sheikh Jed el Karim was again quick to take the chance to continue Myrtle’s lessons during his absence. That year Myrtle added Sheikh Jed el Karim to the locals whom she and Amice Calverley visited at the feast at the end of Ramadan, “as I felt it would not be polite to pass him by since he has been coming here to give me lessons this year. He was very thrilled with the honour as it was the first time Europeans had been in his house”. Sheikh Jed el Karim had married the previous autumn and he “presented his bride to us … also an elder lady who is the wife of his uncle & is living in his house as companion for the young wife. This lady was enraptured with the visit, & when Sheikh Jed el Karim brought the tray with the coffee, she insisted on taking it out of his hands to have the honour of serving us. They had quite a tussle over it. Finally he let her have the tray but himself presented us with a cup each from it, which was a very neat way out of the difficulty”. Clearly her teacher was also a diplomat.

Two months later Sheikh Sarbit was posted to another school at a village nearer his home, and Myrtle told her mother: “I am continuing my lessons with Sheikh Jed el Karim who is only too glad to step into Sheikh Sarbit’s shoes. He is also an excellent teacher”. According to Myrtle, Sheikh Jed el Karim was “a very merry man. He has a round face, rather dark complexion & very black twinkling eyes & a perpetual smile”. He reminded Myrtle “of a robin, he is so quick & perky in all his movements, quite the opposite to Sheikh Sarbit who is more of the languid type”. His teaching style was also different. Myrtle explained to her father that Sheikh Jed el Karim “takes a tremendous interest in my efforts & beams with delight when I make a correct reply, he has not got Sheikh Sarbit’s aloof manner but he is a very good teacher & is just as quick at pouncing on mistakes but he does it in a way as though he were calling my attention to something I had overlooked accidentally. Sheikh Sarbit managed to convey whole volumes of reproof when he simply said ‘this is not correct’. & if I happened to repeat the same mistake his look made me feel like disappearing under the table”.

In her next letter she added that “the enthusiasm of Sheikh Jed el Karim is boundless. I made a few remarks about derived conjugations [verbs formed from the addition of prefixes and suffixes] last week & met with an immediate response. I am going to be swamped & drowned in verbs. He is going to occupy his spare time in writing out examples, he spread out both arms to show me the length of paper he would have to use. I am feeling a little alarmed, he is evidently not used to have a pupil express curiosity in these matters”. Sheikh Jed el Karim was as good as his word and at the next lesson “came armed with a huge sheet of paper covered with verbs that he had written out for me. I had a great time deciphering it. He says quite cheerfully they are just a few for me to start with, & he will do me lots more”. She explained to her mother that “strange things come under verbs. A kitchen is a verb because it is a form of the verb to cook, & the cook & his cooking are also included in verbs. One has to change any preconceived ideas of grammar that one may have had”. At the end of the 1933–1934 season, she thought that “Sheikh Jed el Karim is quite sad that lessons are nearly over … he is so very enthusiastic & bubbling over with information”.

When she returned to Abydos for the next season, in November 1934, she continued her lessons with Sheikh Jed el Karim, who “was delighted to find I had not forgotten my Arabic & says I have made a great improvement during the summer”. During the summer he had been promoted to “head master in a new school in the next village, half an hour’s donkey ride from Arabah el-Madfunah”, and he came by donkey on his way home to give her lessons. That Christmas Sheikh Jed el Karim was again invited to attend the Abydos “fantasia”. Myrtle asked him to sit beside her, so he could “explain some of the parts of the performance that I could not follow easily. He was very much entertained by everything & felt very honoured at being allowed to sit with the Europeans” rather than with the other Egyptians.

Although Myrtle thought Sheikh Jed el Karim was not such an advanced grammarian as Sheikh Sarbit, he was nonetheless an enthusiast for grammatical technicalities. She told her mother that in one lesson “I came across a verb in my dictation that was very involved. I had looked it up in the classical dictionary & from the context I came to the conclusion it was a form that denoted sequence. The sentence was, ‘the sparks (flew one after the other)’; the words in brackets were expressed in one word. I then traced the verb back to its original simple form of three letters. The Sheikh was astonished & delighted, he loves a grammatical discussion”. She had to confess, however, that she “[could] not follow him very far when he gets astride his hobby horse”.

When Dr Hermann Junker visited in January 1935, he was very interested in Myrtle’s Arabic and keen to talk to Sheikh Jed el Karim, so Myrtle invited the sheikh “to come specially, & of course he was highly honoured. Dr Junker asked about all the special greetings that are customary in this district, & found out lots that we had never heard of. Sheikh Jed el Karim is going to write them out for me with all the proper replies so I shall have the correct things to say on every occasion”. Myrtle was always keen to put what she learnt into practice. In her letter the following week, she told her mother they had taken visitors for a picnic in a local wadi, when they slid down the sandslope and “were much entertained by the games our menplayed in the sand. They made holes & buried each other & the one who could remain covered the longest won. I caused much delight by saying the greeting one gives when visiting a house of mourning, which is ‘This happens to everyone, it is the state of the world’. I had just learnt it from Sheikh Jed el Karim so it came in very opportunely”.

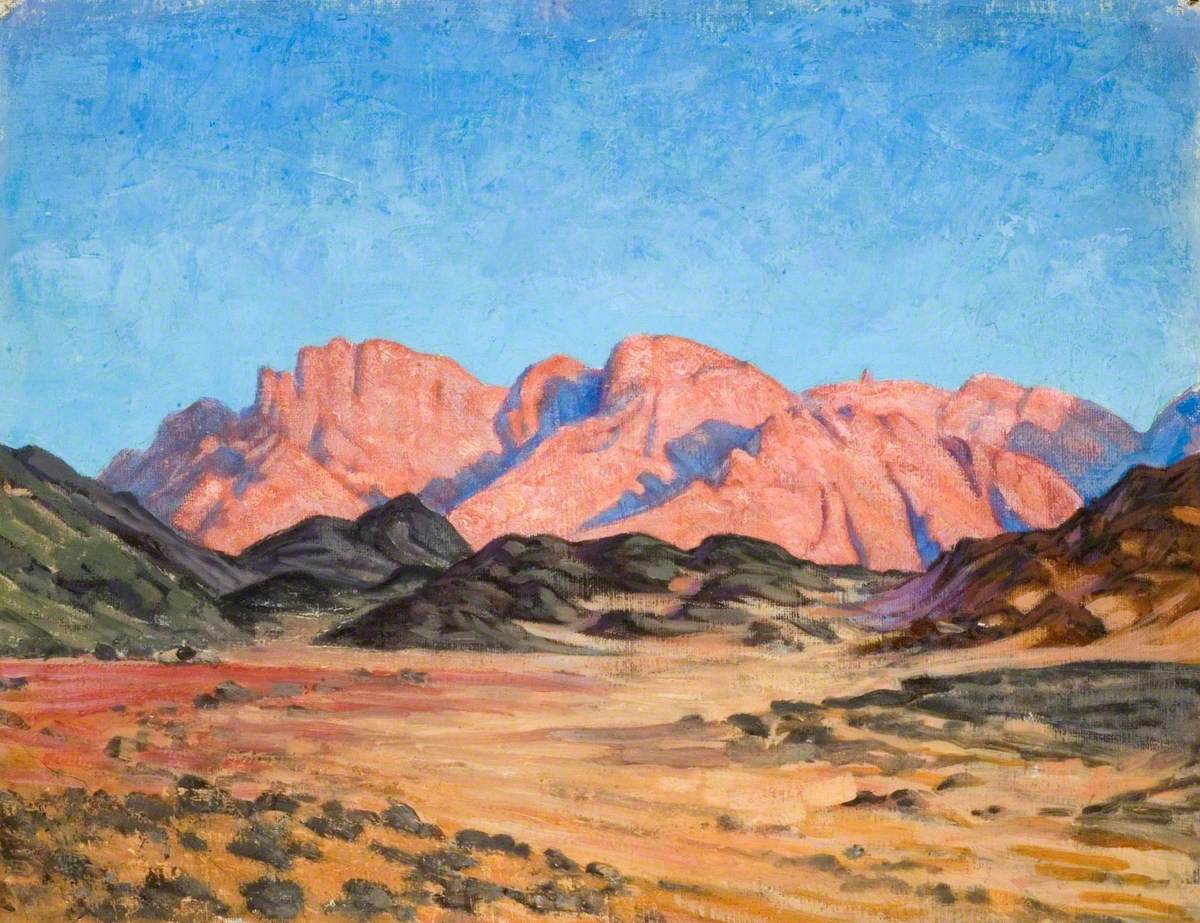

Myrtle Broome

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Paying for her lessons was always a “delicate task”, but Sheikh Jed el Karim “wasn’t quite so difficult to manage as the head-master [Sheikh Sarbit]”. Myrtle told her mother: “He said ‘to be assured of my pleasure was reward enough’, so when I said his acceptance of a gift would double my pleasure, he took the envelope with the 40 piastres & said he was very grateful & there was no more fuss”.

Sources:

Letters: 56, 61, 196, 201, 203, 242, 244, 245,248, 249, 253, 254, 256, 257, 259, 261, 262, 275, 276, 277, 278, 287, 296, 310, 314, 316, 317

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for Myrtle Broome’s paintings

- the Artefacts of Excavation project, for biographical details for Dr Hermann Junker