Learning Arabic – 6

Author: Susan Biddle.

This is one of a series about Myrtle Broome’s experience of learning Arabic. This post is the second of two looking at Sheikh Jed el Karim, the second of her Arabic teachers, and focuses on the imaginative ways Myrtle improved her Arabic and her other dealings with Sheikh Jed el Karim.

Myrtle started formal Arabic reading and writing lessons with the local school master, Sheikh Sarbit, in November 1931, beginning with the alphabet, progressing through the three and four syllable words in the school reading book to “real sentences”, and then to dictation and reading aloud. She moved on to translating proverbs and short stories, as well as writing formal or functional letters, and then to the complexities of Arabic verbs and cursive rather than printed Arabic. During the 1933–1934 season, when Sheikh Sarbit was absent for various reasons, she continued her lessons with his second in command, Sheikh Jed el Karim, who took over completely when Sheikh Sarbit was posted to a school in another village.

As Myrtle’s knowledge of Arabic improved, she developed various methods for extending her vocabulary. In mid-November 1934 she told her mother: “I learn up the words I did not know in my previous lesson, & make two lists, one in Arabic & one in English, each numbered alike. [Sheikh Jed el Karim] has the Arabic & I have the English list & he asks me the words by numbers, I look up the number on my list & repeat the word I have written against it, in Arabic”. She thought that he enjoyed hearing her lists of words. Within three weeks she had evolved a more challenging test for herself, telling her mother: “I now make up a sentence in Arabic using each word to make sure I understand the exact meaning”. As a result she quickly “discovered further complications in the verb, there is a form that denotes a permanent action & another for a temporary one”. When she wanted to say “I saw a splendid relief carved on one of the stones that are raised above the wall of the temple” and “the lamp would give a better light if it were raised up a little”, she was told she must use different forms of the verb “raise up” “since the lamp could be moved, whereas the stone stayed in position”. She asked her mother: “can you imagine anything more complicated than Arabic?”. By mid-February 1935 her system had evolved still further – Myrtle would “ask [Sheikh Jed el Karim] to give me a verb, & then I write it out in the various tenses & moods”. She noticed that “he gets a little worried sometimes & has to think hard, but as for me, my head goes like a whirlwind”.

Her lessons with Sheikh Jed el Karim were not confined to grammatical technicalities and vocabulary lists. After her trip to the Kharga and Dakhla Oases in March 1935, Myrtle wrote to thank all those who had helped her, and “had a lesson from Sheik Jed el Karim on the correct way to do it in Arabic” including appropriate “flowery phrases”. Another lesson in December that year was similarly devoted to writing a letter to the daughter of the local marmur [magistrate], who had recently visited the team working at the Temple of Seti I, to thank her for bringing them a box of delicious home-made feast cakes of walnut shortbread.

Myrtle Broome (1930 or 1935?)

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

On her return from the oases, Myrtle also spent several lessons writing an account of her trip. She did not prepare this in advance, but would “describe it as best I can to the Sheikh & he tells me the correct way of expressing it in the classical Arabic, & then I write it down”. Myrtle noted the progress she had made – she “could not have attempted this a year ago but now find it an excellent plan, as it makes me talk & try to express my ideas without referring to my book. The schoolmaster is delighted with this new way & gets quite excited about my adventures”.

Myrtle appreciated the subtleties offered by Arabic. Wanting to say that she spent two nights staying with the Gedida head man in the Dakhla Oasis, she “used the Arabic for slept ie ‘I slept there two nights’. This did not satisfy [Sheikh Jed el Karim], I might have slept anywhere – in a chair or on the floor”. Instead she was told that she should say “I visited the omdah of Gedida and housed there two nights” as “to be housed for the night means I was provided with all the proper furniture for sleeping in a house”. She thought this “really more sensible than our way”. She certainly had been well-housed at Gedida – she had explained her mother that “the part of the house where I was entertained was a separate wing specially for the entertainment of visitors, it had two large sleeping rooms, a reception room, dining room, serving room & kitchen & a wide veranda all round. All beautifully clean & orderly but very simply furnished”. A simple “slept” would not have done it justice.

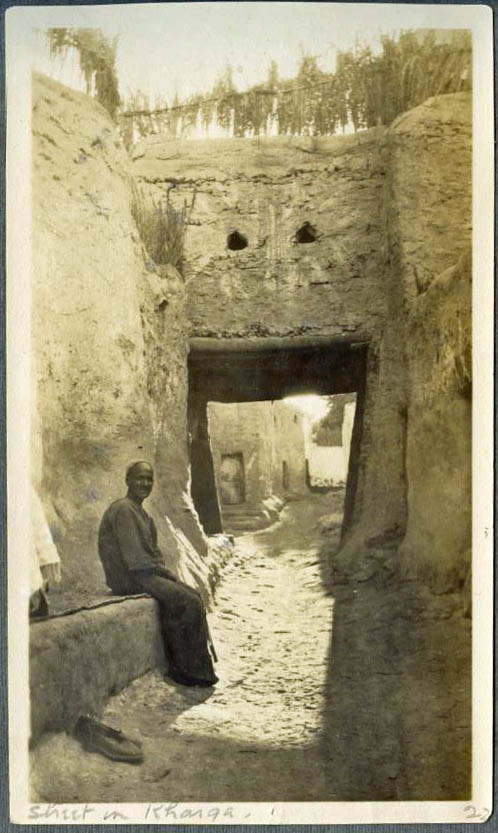

Similarly, Myrtle “had made a long clumsy sentence about the village having a lot of narrow streets. The Sheikh expressed it thus, ‘I visited the village. I found it pierced by narrow streets in all directions’”. Myrtle told her mother that this “describes it exactly, but I should never have thought of employing that word for anything but piercing paper or wood etc”.

Myrtle Broome (1930?)

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

At the end of the 1934–1935 season, Myrtle went to Jerusalem to do some work for James Starkey and took the opportunity to do a little exploring of sites around the city. For her Arabic lessons at the start of the following season, she again wrote an account of these excursions. She told her mother that Sheikh Jed el Karim “is very interested in the description of the famous Mosque of Omar & was quite excited when I said I had seen the rock where the Prophet ascended to Heaven. Of course I show him the picture cards I bought in Jerusalem”.

The Art Institute of Chicago

Photography Gallery Fund

Writing this account occupied several weeks of lessons and sometimes presented challenges. In her 10 December lesson, Myrtle “had a great problem … trying to explain to Sheikh Jed el Karim how the Dead Sea lies below the level of the Mediterranean”. She “managed it with the help of diagrams & he quickly grasped my meaning”. She was still working on her description of the Dead Sea at her next lesson, three days later. On this occasion the Sheikh “was very amused at the description of the people bathing in the Dead Sea. I told him they had to wash in fresh water afterwards to get rid of the salt. He said ‘if there was fresh water to wash in, why did they want to go in the salt water?’ He seemed to think it a strange form of entertainment”.

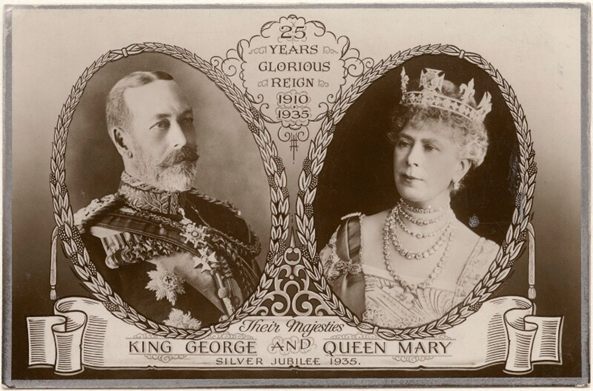

As with Sheikh Sarbit, Myrtle discussed more than lessons with Sheikh Jed el Karim. In February 1935 she told him about the Tower of London and was glad to receive pictures of “Beefeaters” (Yeoman Warders) from her mother as “he will be delighted with the pictures of the solders on guard there”. In April that year she gave him two picture postcards in a series to mark King George V’s Silver Jubilee to show to the school children. Next month she asked her mother to save any good pictures of the Jubilee for her so she could send these to him as “he was so pleased with the postcards”. Perhaps this was one of those postcards:

After Unknown photographer, bromide postcard print, 1935

National Portrait Gallery, Photographs Collection (x196857)

Given by Terence Pepper, 2014

Creative Commons licence

In November 1935 Myrtle “showed Sheikh Jed el Karim the picture of the royal bride” that her mother had sent her, in which “he was very interested”. The Sheikh may, of course, have been simply being polite! This was presumably a picture of the wedding of HRH Duke of Gloucester, the third son of King George V and Queen Mary, to Alice Montagu-Douglas Scot on 6 November 1935 in the private chapel of Buckingham Palace. Perhaps it was this postcard:

By Vandyk, published by J. Beagles & Co., bromide postcard print, 6 November 1935

National Portrait Gallery, Photographs Collection (x197272)

Given by Terence Pepper, 2014

Creative Commons licence

The Sheikh gave Myrtle a rather more useful present. At the start of the 1935–1936 season Myrtle had bemoaned the camp’s lack of a cat to her father. At the end of the previous season, Myrtle had told her mother: “I had a rat in my room last week & had a disturbed night. It is amazing how much noise a rat can make running about”. Abdullah, the youngest servant, had set a trap to catch the rat the next day and “triumphantly produced the corpse hanging by its tail” when Myrtle returned from work in the temple, but one can understand why they wanted a cat to deter rats. A couple of days after writing to her father, Myrtle explained to her mother: “I had a nice surprise yesterday. Sheikh Jed el Karim arrived with a basket in front of him on his donkey & he told me there was a present for me inside it. When I opened it there was a dear little tabby kitten … He had brought it from the village where his school is”. Although trembling with freight after its hour-long donkey ride, the kitten didn’t scratch Myrtle when she lifted it out and cuddled it, and it quickly made itself at home. Two days’ later she reported that the kitten “sits on my lap & purrs and makes puddings. Otto [Daum, another artist member of the team] says he is playing the piano, he behaves beautifully at meal times, drinks up his soup & then sites quite quietly under the table”. By early December, the kitten – named Mugallem, meaning “striped one” – was “very fit & thinks petting is much more important than eating, he is never still one moment”.

Myrtle’s ability to speak Arabic enabled her to connect with people in a way which was not open to those whose Arabic was limited to essential practicalities. There were still sometimes difficulties. When the wife and daughter of the local marmur came to tea in January 1936, Myrtle told her mother that she and Amice “did our best to talk to them in Arabic but we found it rather difficult as we so seldom have to converse on female topics that we found our vocabularies rather limited”. Lack of any nautical vocabulary did not seem to present a problem when two months later, during a brief holiday on the Red Sea coast, Myrtle and Amice were invited to join a Royal Naval Reserve commander in a sailing trip to take soundings as part of his work charting coral reefs. The commander “was sailing the boat with the aid of an old Arab boatman”, but “the commander’s Arabic was very limited; he could only give the necessary sailing directions & could not understand the old Arab’s dialect”. However Myrtle and Amice could understand the boatman, and “the Com. was amazed when we began chatting with the old boy & got him yarning & telling tales of sharks & he showed us two scars on his legs when a shark had got him once, you can imagine what fun we had”. Without the help of Sheikh Jed el Karim, and his predecessor Sheikh Sarbit, Myrtle’s experiences in Egypt – and her letters home – would have been far less rich and rewarding; she and her readers have much for which to thank both Sheikhs.

Letters: 299, 305, 323, 329, 331, 332, 334, 337, 341, 346, 347, 348, 350, 351, 355, 357, 358, 363, 367, 373, 383.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for Myrtle Broome’s paintings and photographs

- the National Portrait Gallery, London, for postcards of George V’s Silver Jubilee and the wedding of HRH the Duke of Gloucester and Princess Alice

- the Art Institute of Chicago, for the image of the Mosque of Omar

- the Artefacts of Excavation project, for biographical details for James Starkey

- Historic Royal Palaces, for information about the Yeoman Warders (or “Beefeaters”) at the Tower of London