Animals – 6: Chickens

Author: Susan Biddle.

This post is one of a series about the animals Myrtle Broome encountered during her eight seasons in Abydos (1929–1937). This instalment looks at chickens and the long Egyptian tradition of incubators.

Both chickens and eggs were an important part of the diet of the team working at Abydos. In January 1930 Myrtle told her mother that they had “splendid egg dishes” and that “when we have chickens, we usually have them stuffed with rice & raisins. You have no idea how good this is. Sometimes the liver is boiled and chopped up with the rice (or it may be giblets)”. They also ate stewed chicken, seasoned with bay leaves or rosemary.

For their six-day trip across the Eastern Desert to the Red Sea coast in February 1935, Amice and Myrtle’s provisions included “a roast chicken, bully beef, 20 hard boiled eggs, biscuits & bread & jam & a rice & date pudding”. Apart from the fresh fish they expected to buy when on the coast, they anticipated to rely entirely on their own resources. For supper the first night, camping in the desert, they enjoyed the cold roast chicken and rice pudding by star light. The following morning, “Sardic[their head servant, who accompanied them] made hot tea for breakfast, & we ate our hard boiled eggs & bread (no butter)”; lunch that day comprised more eggs and bread, plus dates and oranges. The following day they reached the coast and picnicked “among sand dunes where we ate hard boiled eggs & oranges”.

When they left Abydos at the end of their final season to drive back home via the Red Sea coast, their provisions for the first part of the long journey were similar. Myrtle told her mother that “our baker woman is coming tomorrow to make a big baking of bread for us to take with us, & Nannie[their Syrian housekeeper] is boiling lots of eggs”. When they detoured for a couple of days to visit the Roman settlement at Mons Claudianus, they once more breakfasted on tea, eggs, and bread, this time supplemented with cheese, oranges, and apples.

They kept chickens at the dig house so they could provide themselves with all these eggs and chickens. Just before Christmas in the first season, Myrtle reported to her mother that “Ahmud Ibrahim, the chief guard of this district, has presented us with a fine turkey for our Xmas dinner. He (the turkey) is now gobbling in our little farm yard, & lording it over the chickens”. In April 1933, when unexpected visitors arrived and accepted an invitation to dinner, Nannie “had a chicken killed & produced a very nice meal”.

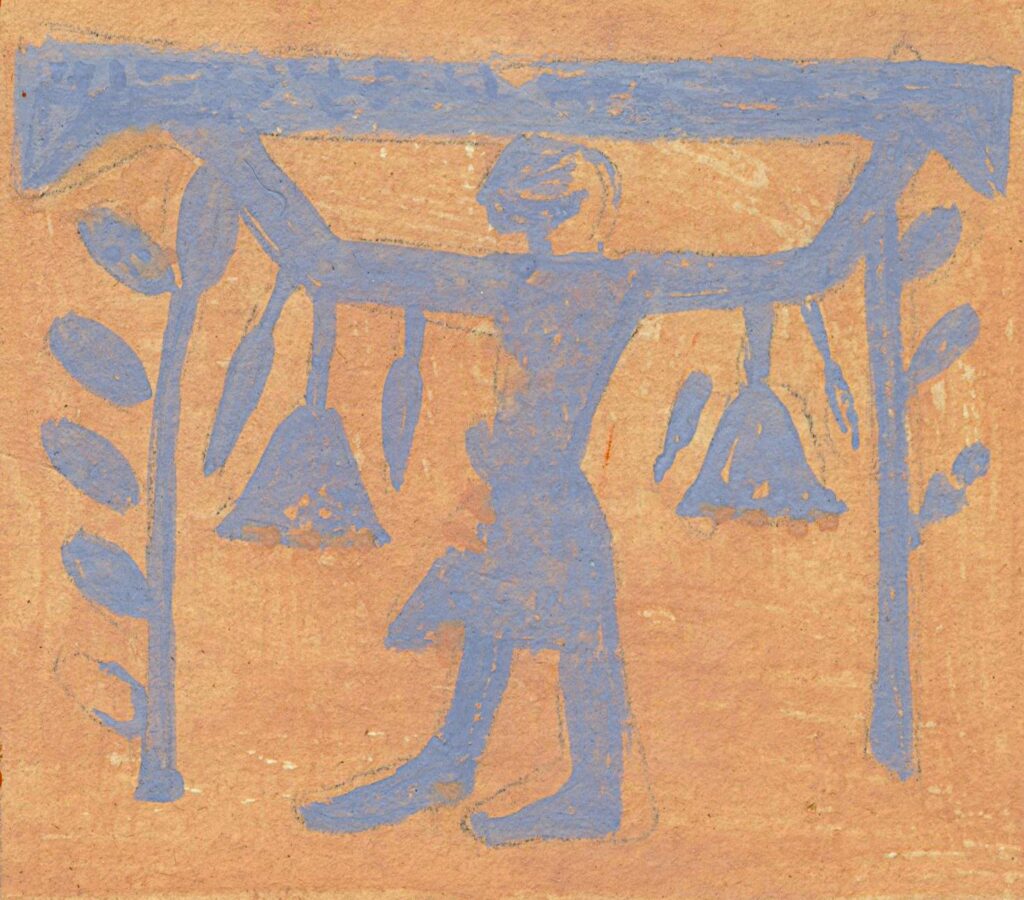

In February 1931 they added to their flock. With two visiting friends of Amice, they drove “to Berdice [Bardis?] where there is one of the ancient incubators still in use”. Myrtle told to her mother that “the industry is carried on by Copts, & the same family has been doing it for generations. They get to know by instinct exactly the correct heat. The incubator is a mud house. There is a long passage down the centre [and] there are little rooms on each side”, and included a sketch of the arrangement in her letter:

Myrtle explained that “the top part is the window & the lower is where the fire is. There is a brick floor dividing them. The eggs are placed in the lower part where the fire is, for so many days, & then transferred to the upper where they are turned so often. The hatched chicks run about in the passage between. There were hundreds of baby chicks running about when we went in”.

She was right that egg incubators have a long tradition in Egypt. Aristotle in the fourth century BCE, and Pliny the Elder in the first century BCE, both wrote that in Egypt eggs are hatched spontaneously in the ground, by being buried in dung heaps. In fact, the dung was the fuel for the incubators. In the first century BCE Diodorus Siculus in Book I of his Library of History indicated that in Egypt “the men who have charge of poultry and geese, in addition to producing them in the natural way known to all mankind, raise them by their own hands, by virtue of a skill peculiar to them, in numbers beyond telling”.

The design of the incubators, and the practices of those working in them, have been remarkably consistent for centuries. In the early 14th century, Simon Fitzsimmons, an Irish friar on pilgrimage to Jerusalem, described an incubator in Cairo: “there is a long narrow house in which chickens are generated by fire from hen eggs, without cocks and hens, and in such numbers that they cannot be numbered”. He explained how “innumerable eggs” were placed in ovens for 22 or 23 days, at which point “all these eggs emit chickens in such numbers, that they are sold not by number, but by measure like wheat”. He was more interested in the egg incubators than the pyramids, which he dismissed in a line and a half.

Oxford, Bodleian Library MS. Bodl. 972, fol. 4r

© Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

At the end of the 15th century, another pilgrim, the young German traveller Arnold von Harff, visited Cairo. He explained in his travelogue how eggs were placed in round cups in little holes in stoves, which were then packed round with dung and a slow fire lit underneath “so that the fire, the hot dung, and the hot air of the country, working together, turn the eggs into chickens in three weeks”. Like Fitzsimons, von Harff saw a merchant selling hens “in a measure, pressing them in with both hands, as if he were selling wheat”.

In 1687, the French traveller Jean de Thévenot described how at an incubator in Cairo eggs were put in twelve mud-brick ovens arranged in two storeys each comprising three ovens, the ovens being separated by a corridor through which passed the workers, who were all Copts, and those who – like Myrtle and her friends 250 years later – came to view the incubators. These ovens were gently heated for ten days, using hot ashes and camel dung, after which the eggs were placed on tow or flock on the floor of the ovens for twelve days before hatching. Again, so many chicks were produced that they were sold by the bushel. De Thévenot said that these incubators operated for about four months from February each year, during which time more than 300,000 eggs were processed, though not all hatched successfully.

Relation d’un voyage fait au Levant (1664), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (Thévenot) and Wellcome Collection, Creative Commons by 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons (Réaumur)

In 1750, the French entomologist René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur also thought that “Egypt ought to be prouder of [these ovens] than of her pyramids” and gave a detailed account of various incubators described by earlier authors, which again are all similar to that visited by Myrtle. He explained how the Egyptians assessed whether the oven temperature required adjustment by putting the eggs gently against their eyelids.

In 2009, the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations published a technical report on traditional hatcheries in Egypt. There were then still at least 22 traditional ones in the Sohag governorate where Baliana and Bardis are located. Just as in 1750, the operation was seasonal, with the peak capacity (and higher hatching success rates) from January to April. Myrte’s visit in February was therefore at the busiest time of the year. Most hatcheries were still dome-shaped structures of sun-dried mudbrick which assisted temperature regulation, on foundations of brick. Like the example Myrtle visited, the hatcheries were divided longitudinally with a central passage where the hatched birds dried and fluffed out, and each contained eggs and birds at different stages of production. Hatchery workers still judged when an egg had reached the proper temperature by placing it against their eye sockets, just as de Réaumur had described 250 years earlier.

The men running the incubator showed Myrtle, Amice, and their visitors around and they “bought 17 chicks for 2/- & took them home in a basket. Some are for Nannie to raise, & the others for Sardic’s two little girls. They seem very strong & healthy”. The chicks subsequently provided entertainment to the dig house team, as well as eggs. Eight days later Myrtle reported to her mother that “our baby chicks are thriving wonderfully. Our men have made them a playground outside the kitchen quarters. I took them out some digestive biscuit crumbs to-day & they came & pecked out of my hand crowding on it & pushing each other off. When nearly all the crumbs were gone, one enterprising chick began scratching like a grown up hen. I am afraid it produced nothing, but it did feel funny”. Three weeks later she gave her mother an update: “our baby chicks are getting on splendidly. We sometimes give them jumping exercise by holding a piece of bread just out of reach so that they have to give a very big hop to peck it. They have great games with it, & seem to enjoy the fun. They are developing wings & tails, & the cocks are sprouting combs”. In her next letter she told her mother that “our baby chicks still cause us a lot of amusement. They are getting so big that they can get out of their pen. Sardic talks of making a walled enclosure for them”.

It was lucky they did increase their flock, since they consumed a fair number of chickens. By the sixth season the team had expanded, and Amice was concerned that she had “underestimated the cost of the larger staff, especially the food supplies. She had reckoned that six people would eat twice as much as three”, but found that “the two Austrians eat as much as the four English & they don’t reckon a meal as a meal at all, unless they have huge helpings of meat. When we have chickens, Erica & Otto have one between them. We four others share the remaining chicken”.

The camp chickens perhaps provided a further unexpected benefit for one of the team, Charles Little, who worked at Abydos as an artist between March and May 1930 and again in the 1932–1934 seasons. In February 1937 Amice received a letter from him reporting that “he is married & settled in England. He has a job as handy man on a chicken farm & his wife is secretary to the manager”.

Sources:

Letters: 53, 69, 88, 99, 118, 121, 122, 128, 129, 188, 195, 230, 279, 321, 370, 371, 372, 397, 399, 409.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection and the Abydos Enterprise correspondence within the Gardiner collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- Traverso, V. “A hatching system devised 2,000 years ago is still in use in rural Egypt”, Atlas Obscura (29 March 2019)

- Corti, E. and Vogelaar, E., The Oldest Hatcheries are still in use (2012)

- Resor, C., “Age-Old Cultural Circuit of Egyptian Chicken Hatcheries”, Teaching with Themes

- Hoade, E., Western Pilgrims: the itineraries of Fr. Simon Fitzsimons (1322-23), a certain Englishman (1344-45), Thomas Brygg (1392), and notes on other authors and pilgrims (1952, reprinted 1970)

- Letts, M. (ed.), The Pilgrimage of Arnold von Harff, Knight from Cologne through Italy, Syria, Egypt, Arabia, Ethiopia, Nubia, Palestine, Turkey, France, and Spain, which he accomplished in the years 1496 to 1499 (1946)

- Thévenot, J. de, The travels of Monsieur de Thevenot into the Levant (1687) [Book II, Chapter XI]

- Réaumur, R.-A. F. de, The Art of Hatching and Bringing Up Domestick Fowls of All Kinds, at Any Time of the Year (1750)

- Abd-Elkahim, M. A., Thieme, O., Schwabenauer, K., and Ahmed, Z. S., Mapping traditional poultry hatcheries in Egypt AHBL – Promoting strategies for prevention and control of HPAI (2008)