Animals – 9: Camels – 2: Preparations for the first camel trek

Author: Susan Biddle.

Myrtle Broome’s love of animals shines through many of her letters. This post is one of a series looking at the animals she encountered, and is the first of two describing the first long trek she and Amice Calverley made into the desert after learning to ride camels. This instalment describes the preparations for that trek; the next will cover the trek itself.

An experienced horsewoman, after making just two camel rides, Myrtle was keen to make her first proper desert trek. Accordingly, she and Amice Calverley planned to visit the Kharga Oasis by camel for their leave in February 1930. On 10 January she explained to her mother that the route was via an ancient camel track across the desert and “it takes a good camel rider 3 days & two nights; it is over 100 miles, & desert all the way”. At that time Kharga was seldom visited by tourists because of the difficulty of getting there. It could be reached only by a day’s journey on a train and trolley, which ran once a week on a single line laid about 20 years earlier starting south of Baliana, or by camel.

Unknown photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

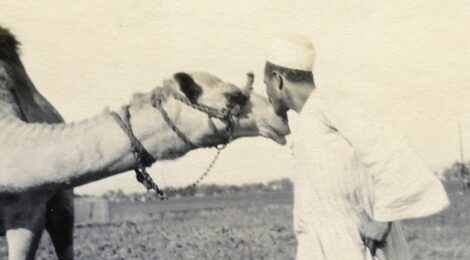

Several Bedouin in the village near the dig house had made the journey by camel many times, and two agreed to act as guides. Two of their servants would accompany them as well. Myrtle reported back home that they would “need 10 camels as one has to carry all the water required for the journey & a good allowance over in case of any delay”. She and Amice would take one tiny tent in which to dress and undress, but would sleep in the open in sleeping bags and blankets on the sand; they would stay near the camels and men because of the threat from wolves and hyenas. Sardic, the head servant, was “very thrilled at the idea. He is a real Bedawi, he belongs to a tribe of camel men & tent makers & … the desert is in his blood & I believe he loves camels more than his own children”.

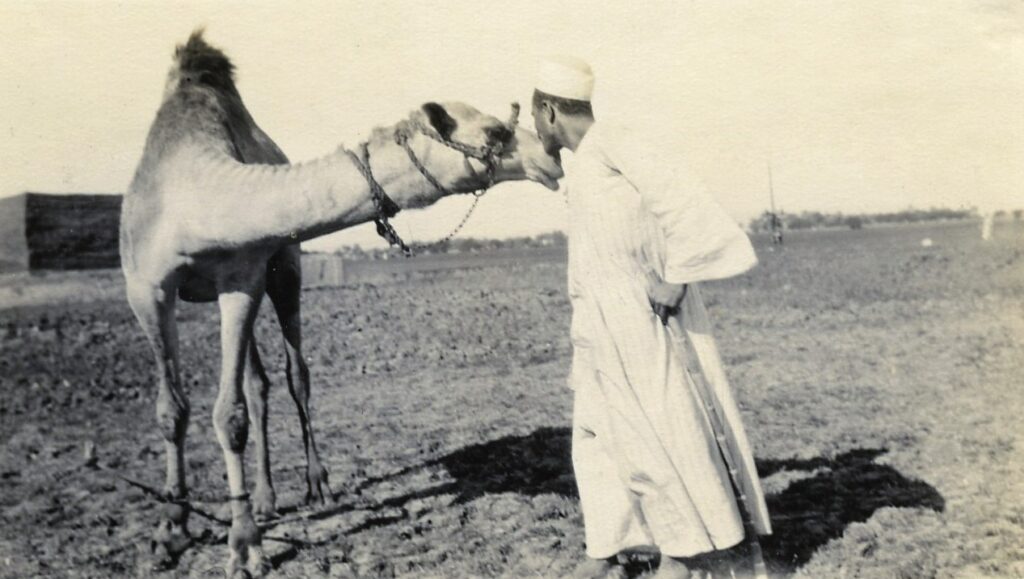

Photography by Myrtle Broome (1929)

Bushey Museum & Art Gallery

By early February they were researching the logistics of the trip in more detail. Myrle explained to her mother: “we have to find out if we can hire camels who are trained to drink once in three days or so. Ordinary village camels who are used to being watered every day are no use for this trip”. They were going to make enquiry of the men who made the journey to transport green dates, whom Sardic was to bring to see them. Meanwhile the inspector of police had offered to lend them proper riding saddles belonging to the police force. She and Amice were getting very excited at the idea, but Myrtle reassured her mother that “of course we shall not attempt it unless we are quite sure we can obtain everything suitable”.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

Three days later she was able to report that they had arranged to hire seven desert-going camels along with their camel men. She said the men “do look a band of glorious ruffians fit for some of the 40 thieves, but they are really perfectly respectable & well-intentioned individuals”, who were delighted to be engaged for the trip. Hassan, the date merchant who went to Kharga every date season, had agreed to act as their guide, and the inspector of police was also going to lend them special skins to carry their water supply. Amice would take her revolver, and Sardic and the other men would carry rifles. Myrtle could hardly believe it was true and thought that “it sounds like some of the tales we read”.

Others were less enthusiastic. Myrtle acknowledged that the local Marmur [magistrate] was “very troubled about us, he says we shall die of tiredness, our backs will be broken in two, & there is nothing to see but sand & rocks”. He suggested instead that they “have a nice comfortable motor car & go to a place where there is pretty scenery, educated people & good shops”, but they just laughed at the idea. Hermann Junker, the head of the German Institute, and Dr Baraize, the French Inspector of Monuments, both did their best to dissuade Amice when she was in Cairo, telling her that “it was a most dangerous undertaking to travel across a waterless country with only a native guide & servants. They told her all the awful things that might happen & she came back from her visit feeling very depressed about it”. However Amice and Myrtle discussed it together and then consulted Sardic, who said: “oh yes, certainly such things might easily happen if suitable camels were not taken or if certain precautions were not arranged properly but he would see we had proper camels & everything required”. Myrtle and Amice weighed up the advice of “a Frenchman & a German, both excellent men, knowing the country for many years, but also having decided ideas about a woman’s limitations; on the other side a Bedawin Arab, a trusted servant & willing & eager to take all the risks with us, & with a firm belief that the English ladies could do anything they attempted, & we finally decided to take an Arab’s word & go”. Their guide later told them that, so far as he knew, they were the first Europeans to take the old camel trail for 25 years.

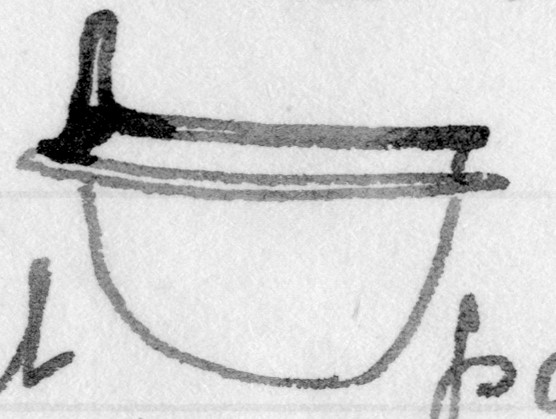

The next difficulty was the police inspector reneging on his offer to lend them riding saddles, ostensibly because there had been trouble in a nearby village which might require significant police presence. However Myrtle told her parents: “we have good reason to believe this failure on the Marmur’s part was a ruse to stop us. He thought we would not go without the proper saddles, & he knew there were no others to be had. The excuse about the turbulent village was mostly bunkum as camels wouldn’t be used in a local rising”. If so, his ruse failed – undeterred, Myrtle and Amice invited the local camel man to visit them with his camel and pack saddle, to see whether this could be adapted for comfortable riding. In her next letter, Myrtle described how the pack saddles would be modified, explaining that “the ordinary pack saddles are like this:

Two poles covered with grass matting, with padding underneath to fit the hump. The loads are slung on the poles, you can imagine it is not exactly easy or comfortable to sit on for long”. However, the local carpenter had “fixed poles up in front like the proper riding saddles, like this:”

Myrtle and Amice would then strap thick pillows on the seat and, Myrtle thought, “with the pole to steady us when the camel sets down & gets up we ought to be quite comfortable”.

Amice invited a friend to join them, a Miss Alexander whom Mrytle found “charming, a young forty, very jolly, a writer, making a leisurely journey round the world”. Miss Alexander was “delighted to have such an unusual opportunity” and had taken several camel rides in Cairo to prepare herself for the journey.

They would not go hungry. Amice, Myrtle, and Miss Alexander would take “food for six days, three roast chickens, 6 tins beef, 1 salmon, 40 loaves, jam, biscuits, Bovril, tins of fruit etc”, with the men taking their own food. The Marmur had also gone back on his offer of water skins, but they bought two new skins for the men’s water and would take their own in petrol tins. They also took a small stock of medicine “& a little brandy in case of accidents”.

All seemed set fair but then, the afternoon before departure, their guide “sent word to say he had a belly ache & could not come”. Myrtle commented cynically that “probably the belly ache was also provided by the Marmur”. Again, if this was a ruse, it failed. Mrytle told her parents that “Sardic knew of another guide from a further village, so we sent to him & the sporting old boy said he would come, & promised to meet us at the entrance to the wady soon after dawn the next day”.

At 6 a.m. on Sunday 9 February 1930 the “cavalcade had assembled. There were 7 camels & 7 men. We carried our own personal effects, rugs etc & a sack of camel food on our camels, & the four others took water & provisions, our little tent & the rest of the camel food, & the men took turns to ride”. By 7 a.m. they were on their way. All their camels “wore neat little cotton bags tied on to their bridles, [which] contained little texts from the Koran that Sheikh Abdu Wahid [who sang the Koran to them in the Temple of Seti I at Abydos] had written specially to protect us all on this journey”.

For the first four miles, the rest of their servants, their guards, and friends of the camel men escorted the party. At the wadi entrance, the party was met by the replacement guide and his camel, “a supercilious lady who proved an amusing, though rather troublesome member of this expedition, as she was a dreadful flirt, & two of our gentlemen camels fell in love with her”. At the top of the wadi they said goodbye to their escort “with many blessings & good wishes for our safety & set out on the great adventure”.

Sources:

Letters: 53, 60, 61, 62, 64.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for Myrtle Broome’s photograph of Sardic with a camel

- the Trustees of the British Museum, for the image of the riding saddle

- the Artefacts of Excavation project, for information on Hermann Junker