Eyes and Teeth

Author: Susan Biddle.

This post looks at the different solutions the team at Abydos adopted for dealing with dental crises, and at some of the eye problems experienced by members of the team and the locals.

The first member of the team to have a dental problem was the cook. While Amice Calverley and Myrtle Broome attended a festival at Qena on Wednesday 15 January 1930, the cook “celebrated our absence from home … by calling in the local barber to pull out a double tooth that had been aching”. Unfortunately “the result was the tooth was broken off short & the poor man was nearly crazy with pain”. Amice sent him off to the American Mission Hospital in Asyut first thing the following day with Sardic to look after him. The pair returned on Friday morning, “the cook proudly displaying three awful fangs”, and Myrtle told her mother that “they both seem to have quite enjoyed the experience”. The cost of the cook’s hospital treatment was paid for by the expedition.

Courtesy of Union Presbyterian Seminary Library Digital Collections

When Amice lost a “stopping” (filling) from a “double tooth” (molar) on Sunday of the same week, she was not tempted to trust to the local barber’s treatment. Instead she took a week’s leave early and went to Alexandria for dental treatment. She returned to camp ten days later, but the very next day “after lunch, she had another rather important stopping come out of a tooth”, so had to return to Cairo on that evening’s train to go to the dentist yet again. Amice does not seem to have had much luck with her teeth. In March 1930 she missed the visit to the temple by the Queen of the Belgians because she had had to visit the dentist again when he meant “to finish her properly this time”.

The following season it was eyes, rather than teeth, which were the problem, with many of the local people suffering ophthalmia – conjunctivitis or inflammation of the eye and eyelid which may be caused by viruses, bacteria, fungi, parasites, irritants, or allergies. If untreated, it can cause loss of vision, particularly in new-borns. In March 1931, Myrtle told her mother that “there have been a lot of people lately with ophthalmia, most of them hopeless cases. They don’t realize it is serious until the sight is destroyed, & then of course nothing can be done”. A week later she wrote, even more worryingly, that “there are a lot of cases of ophthalmia among the babies. Amice is going to report it to the authorities of this province as it is so very infectious & with all these flies about will become an epidemic in no time”. She explained that “the people’s superstitions make it very difficult to deal with them, of course our supply of bandages is limited so when it is a fairly long case we use two bandages & tell the women to wash one in soap & water every day, but they will not use soap in connection with any form of illness. They consider it highly dangerous, directly any one is ill or hurt they throw away any soap they may have & will not allow any of the people to use any at all. They say if soap is near a sick person he is sure to die – & if his clothes are washed with soap he is as good as buried … And they encourage the flies in the children’s eyes because they say they protect them from the evil eye”.

More cheerfully, the following month Myrtle was able to report that the three-year-old daughter of Mahmud, one of servants, had been successfully treated for ophthalmia, and her eyes were quite all right again. Myrtle had given Mahmud’s wife an old frock she had brought to wear in the evenings – “a sort of fawn with roses & pink crepe-de-chine let in to the skirt” – to make a dress for her daughter. The little girl had come in wearing it that evening “as proud as punch”.

The next year, in January 1932, it was Amice who had trouble with her eyes. Myrtle attributed this to Amice’s work with Linda Holey, who had been recruited that season to photograph the temple reliefs. Amice had been helping Linda with the reflecting mirrors needed to light the photographs “& the changing from the shaded light in the temple to brilliant sunshine reflected from a mirror surface was very bad for her, she could not get her focus right again for some time”. Amice herself thought it was an after effect of flu, combined with over-work. When the problem persisted for two days, she consulted an oculist, Dr Max Meyerhof, who said it was “a form of strain caused by too much work – more due to brain & nervous system than eyes” and prescribed a week’s rest if the problem recurred.

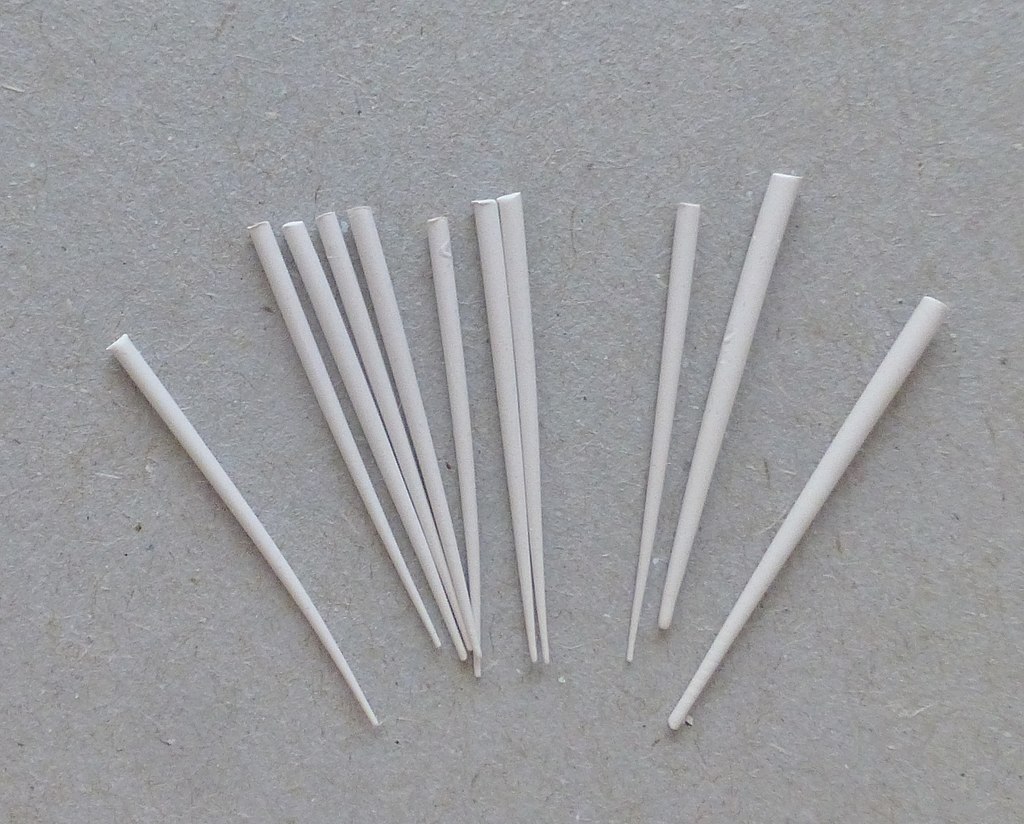

In the 1934–1935 season there were problems with both teeth and eyes again. In November Amice lost another filling and, rather than go to Cairo, she “wrote to a dentist in Cairo to ask if he could send something for a temporary stopping” and asked Myrtle to play dentist. Myrtle told her mother that the dentist “sent a little stick of white gutta percha which we had to warm & push into the hollow tooth. So far it has been quite successful”.

Photography by Alutal, CC BY-SA 4.0

Gutta percha is still used in root canal dentistry today. The camp was equipped with some dental tools though these were also used for other purposes – in December 1931 “an alteration had to be made to one of the lens fittings on the camera which required a very delicate screwdriver. Of course we hadn’t one small enough, so Amice used a dental tool!! We find a use for everything here”.

In January 1935 Sardic, the head servant, had trouble with his eyes, so Amice took him to Cairo to see Dr Meyerhof. Amice had taken Sardic to consult the same specialist some years before when he had advised “there was a very slow growth forming (trachoma) & it was best to leave until it reached a certain stage & then he could remove it”. Amice took advantage of the visit to Cairo to get her tooth re-filled, “the gutta percha has filled the breach nobly – but she thinks it’s wiser to have it seen to the first opportunity”. Sardic remained in the Cairo hospital for a fortnight after an operation to his eyes and then returned to Abydos. He was sorely missed – in February Amice told Dr Alan H. Gardiner, the editor of the first three volumes of The Temple of Sethos I at Abydos: “you will realise what doing without Sardek is! He being our mainstay for so many things – we can’t tackle night photography until he is back & fit for it – none of us can turn the crank to start the engine let alone put up the big scaffolds needed – I do hope for his own as well as our sake that he recovers soon”. On his return, Sardic’s eyes seemed much better for a while, but they then became inflamed and painful again. Amice took him to the eye hospital in Sohag, where he stayed a week as his eyes “need proper dressing several times a day. The eyelashes are inclined to grow in under the eyelids & this causes inflammation”. Amice gave a copy of volume I of The Temple of Sethos to Dr Meyerhof as a thank you for the operation on Sardic’s eyes, and was reimbursed the £4 cost of this by the Egypt Exploration Society.

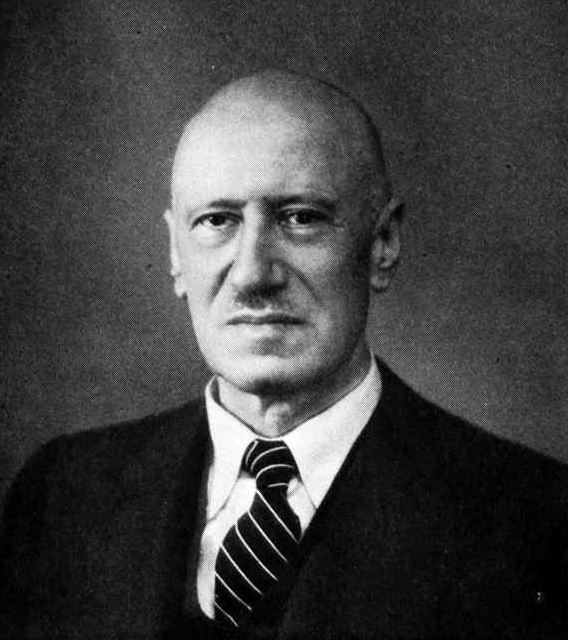

Max Meyerhof was born and educated in Germany, where he studied medicine and specialised in ophthalmology. For health reasons he spent the winter of 1900–1901 in Egypt with his cousin Otto Meyerhof (Nobel prize winner for medicine in 1922); another cousin of his was the Egyptologist Wilhelm Spiegelberg. In 1903 he took charge of a clinic for eye-disease in Cairo, where he developed a thriving medical practice and researched infectious ophthalmias. He was a founder member of the Ophthalmological Society of Egypt and also studied medieval Arab ophthalmology. During the First World War he worked as an army surgeon in Germany, but in 1922 was granted a special permit to return to Cairo to resume his medical and scientific work. In the inter-war period his research extended to the whole history of Arab medicine and science, on which he published extensively. He treated many of his poorer patients without fees and saved many from blindness. When Hitler came to power, he resigned his German nationality and became an Egyptian national in 1935/36. Clearly both Amice in 1932 and Sardic in 1935 were in experienced hands.

Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

At the end of the seventh season, in April 1936, Myrtle had her own eye problem: she mislaid her spectacles. On arrival in Cairo on the first leg of her return journey to England, she wrote to her mother: “I find I must have either lost my glasses or left them in camp”, and asked her to look out her prescription “& send it to Father’s spectacles man to make me another pair, same as before”. She had an emergency pair, “but they are the first I ever had with ear pieces & gold rims like Father’s, & are not quite the proper focus”. The years of close work may have affected her sight – in July 1939 in answer to an enquiry from Dr Gardiner, Myrtle told him her eyes were “better for the rest, but I have to be careful with them, I have to use fairly strong glasses for fine drawing, but for reading & ordinary work my sight is quite good”.

Sources:

Letters: 54, 55A, 59, 74, 129, 131, 133, 151, 157, 164, 301, 311, 313, 319, 378.

Gardiner MSS 43 – Calverley Correspondence, Letters 91, 138, 139.

Gardiner MSS 43 – Broome Correspondence, Letter 186.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and the Abydos Enterprise correspondence within the Gardiner collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Egypt Exploration Society, for access to their Amice Calverley Archive

- the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago, for the online copy of The Temple of King Sethos I at Abydos, Volume I and biographical details for Wilhelm Spiegelberg

- the Artefacts of Excavation project, for biographical details for Dr Alan H. Gardiner

- Joseph Schacht, for information about Max Meyerhof, in his article: Schacht, J., “Max Meyerhof”, Osiris 9 (1950): 7–32 [http://www.jstor.org/stable/301841]

- the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, for the obituary article about Dr Meyerhof