Flying – 1

Author: Susan Biddle.

During the 1930s air travel moved from being the preserve of pioneering aviators and the rich to scheduled air services within the reach of a wider, though still well-off, public. This post is the first of a series of three looking at Myrtle Broome’s encounters with air travel and, eventually, her own flying experiences. This post focuses on the period from 1929 to 1931, including a record-breaking flight to South Africa.

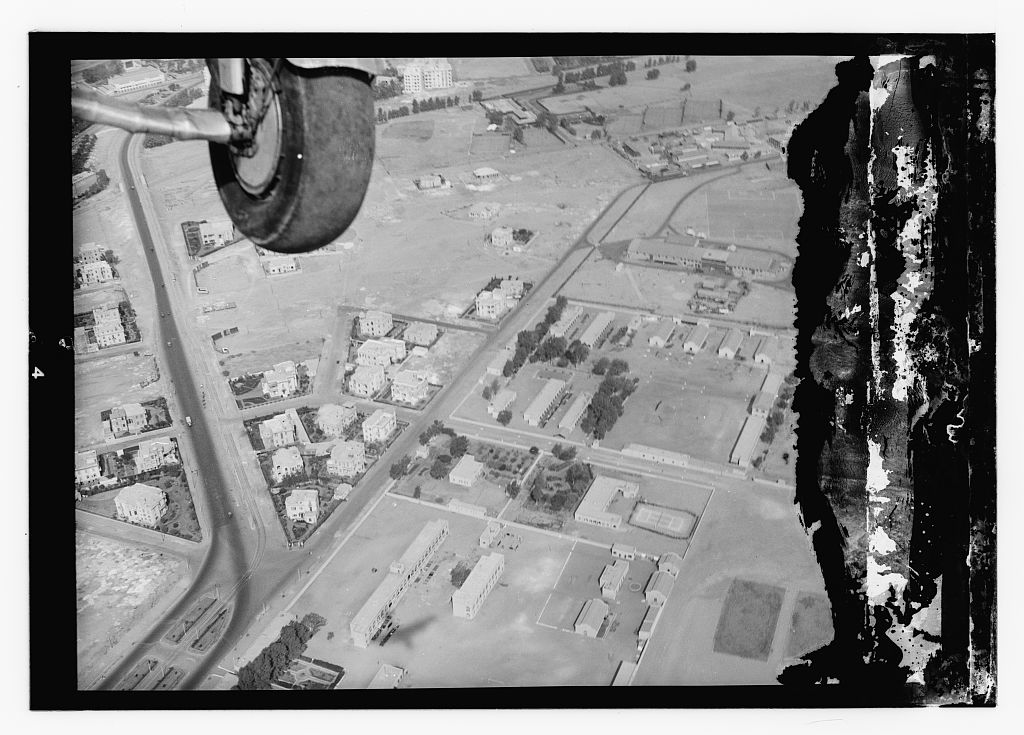

When Myrtle Broome arrived in Egypt in October 1929 at the start of her first season working at Abydos with Amice Calverley, she registered at the British Consulate immediately on arrival in Cairo, telling her parents that this was “so that they know where I am to be found should anything unforeseen arise”. For example, in the case of local unrest, “the RAF would send a plane to Abydos to pick us up”. The RAF at this time had various bases in Egypt, including Aboukir, the home of the central depot of the RAF Middle East until 1939, and Heliopolis, which became the first base of the Egyptian Army Air Force in 1932 (now Almaza air force base). Myrtle’s thoughts on the possibility of air rescue are clear: “Wouldn’t it be thrilling”.

From the G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection

US Library of Congress

A few days later Myrtle reported that they were to lunch with an RAF officer who was “to give us instructions & measurements so that we can look out for a suitable landing base for one of his aeroplanes near our camp”. Myrtle looked forward to the possibility of entertaining “flying men”, as well as noting that a landing strip “also gives us a third line of retreat should anything happen to the railway or the Nile traffic”. Again, it seems she was excited rather than scared by such a possibility, though she was perhaps also trying to reassure anxious parents, telling them: “we are feeling important and adventurous. We almost hope something will happen – it would be so thrilling to be rescued by aeroplanes. But of course nothing like that is in the least likely to happen”. No air strip was ever created for the Egypt Exploration Society team at Abydos, though the possibility was discussed again in later seasons.

Towards the end of the first season Myrtle told her mother that when the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VIII, flew over Abydos, “we saw the plane he was in & the escort following. They passed right over the temple. Of course we all went on the roof & waved”. The Prince of Wales had been on safari in Kenya and Uganda during the winter of 1930, at the end of which he flew back from Khartoum to Cairo. In the same letter Myrtle indicates she expected that “Charlie Barnard came over also, on his way to the Cape & back, but we did not know till afterwards so did not look out for him”. This was Charles Douglas Barnard (1895–1971), a British pilot who participated in several 1920s air races and record-breaking flights. After serving in the Royal Flying Corps in World War I, he co-founded Brian Lewis and C. D. Barnard Ltd for sales of De Havilland aircraft, based at Heston Aerodrome, and became the personal pilot and instructor to Mary Russell, Duchess of Beford, who became known as the “Flying Duchess”.

On 10 April 1930 Barnard, accompanied by the Duchess and a mechanic, Bob Little, took off for Cape Town from Lympne Aerodrome in Kent, in the Duchess’ aeroplane, a Fokker F-VIIA called the ”Spider”. They arrived on 19 April, after a record breaking 91 hours 20 minutes flying time over 10 days.

Unknown photographer

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

At the start of the third season, in November 1931, Amice persuaded the RAF to “lend” them Leading Aircraftman Clark to put the Abydos electric engine in order. She must have been very persuasive as “it seems that all the RAF regulations had to be uprooted to let him come, since the men are not granted leave of absence so far from headquarters since some soldiers were murdered on the line a year or so ago”. LAC Clark seems to have enjoyed his break from routine. Myrtle describes him as “an extremely jaunty & lively young man” who “made himself very much at home, was thrilled by our life out here & was very much tickled by the Heath Robinson-ish fixtures we have to work with”. Luckily LAC Clark was also competent. After “hoots of laughter at the state of the dynamo and ignition timing”, he soon fixed the engine which “began to purr like a contented cat”. That evening Amice and Myrtle “took him for a ride over the desert in Joey [Amice’s Jowett car] to look out for a suitable landing ground for aeroplanes. He showed us what was needed. Length – direction etc & how to mark it out, & is going to report the possibilities to the Commander who is very anxious to pay us a visit”.

After LAC Clark’s visit, Myrtle indicated to her mother that she was “thinking of writing to Charlie Barnard & telling him we have a possible landing for planes in case he might like to pay our camp a visit”. It seems that the Broome family may have known the Barnards personally as later that season Myrtle told her mother she was “so glad to hear all the news about the Barnard family, you must have enjoyed seeing Mrs B”. The 1911 census shows the Barnard family living in Oxhey, about a mile away from the Broomes in Bushey (though Charlie was then away at school). Charlie’s father, another Charles Barnard, was a printer who might, in the course of business, have met Myrtle’s father, a publisher who ran the Old Bourne Press, and Charlie’s aunt Nellie was an artist who may have been another connection with Myrtle.

In 1932 Barnard wrote an account of his 1930 trip to Cape Town with the Duchess of Bedford as part of a series called “My most thrilling flight”, published in the second issue of the new magazine Popular Flying and later collected in a book titled Thrilling Flights. The thrills he recounted included heavy rain, which forced them to fly only a few feet over the heads of giraffes and an elephant on the way out, and carbon monoxide poisoning from a broken pipe on the return flight. Both the magazine and the book were edited by W. E. Johns, author of the popular fictional airman Biggles who had made his first appearance in print in “The White Fokker” in the first, April 1932, issue of Popular Flying. Johns’ aim for the magazine, set out in his editorial in the second issue in May 1932, was “to leave no stone unturned to banish the notions … which confine aviation to a chosen few, either wealthy or possessed of a physique beyond ordinary standards. … Flying is now within the reach of everybody. … Sooner or later, everybody will fly, because it is the quickest, easiest and most pleasant form of transportation yet discovered”. At the end of his account of his “thrilling flight”, Charlie Barnard observed that just two years later it was “possible for anyone to book a passage by the regular Air Service from London to the Cape, confident in the knowledge that wireless, regular weather reports, and organised aerodromes have transformed what was once a hazardous adventure into a safe and rather prosaic experience”. Myrtle’s own experiences during the 1930s bore out these views of the increasing democratisation of flying.

Sources:

Letters: 29, 31, 85, 149, 180.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- Ellis, Peter Berresford and Jennifer Schofield, Biggles! The Life Story of Capt. W. E. Johns Creator of Biggles, Worrals, Gimlet & Steeley (1993), for information about the Popular Flying magazine

- US Library of Congress, for the image of Heliopolis