Flying – 2

Author: Susan Biddle.

During the 1930s air travel moved from being the preserve of pioneering aviators and the rich to scheduled air services within reach of a wider, though still well-off, public. This post is the second of a series of three looking at Myrtle Broome’s encounters with air travel and, eventually, her own flying experiences. This post focuses on the years 1934 and 1935, and includes Myrtle’s first flight.

Until the end of the 1933–1934 season flying had no impact on Myrtle’s own life; she and Amice did not even use airmail for their letters home. In March 1931 Myrtle explained to her mother that although they had lots of airmail stamps, they found that “it doesn’t save very much time as it only goes by air from Egypt to Athens, then by Simplon Express to Paris, & Paris to England by air”.

However, on 2 May 1934 Myrtle excitedly told her mother: “Another thrill. I have added still another mode of conveyance to my list. I have had my first flight”. The previous day Myrtle and Amice had visited Professor Oliver in his house at Burg el-Arab, travelling by plane from Heliopolis to Alexandria before continuing by car, and returning the same way in the evening. Myrtle does not say which airline they used, but by May 1934 Misr Airwork offered daily flights leaving Cairo airport at 8.30 a.m. and arriving at 9.50 a.m. at Alexandria airport, with return flights leaving Alexandria airport at 4.30 p.m. and arriving at Cairo airport at 5.35 p.m. Single flights usually cost PT 100, and return flights PT 200.

Myrtle had first met Professor Oliver in February 1931, when he and his wife were two of a group of “inconvenient visitors”, friends of a friend of Amice, who had turned up in Abydos requiring accommodation despite being told that it was not convenient. Myrtle had told her mother then that “the old professor was very fussy. He said the room was too stuffy & he’d rather sleep on the terrace where we have our breakfast, so his bed had to be made up there, then they all wanted hot water & hot water bottles. Then in the morning they nearly drove poor Nannie [the housekeeper] desperate by demanding lots of hot water when she was in the midst of getting breakfast (it all had to be heated in kettles on the primus so you can imagine the difficulty)”. Professor Oliver was not mentioned in Myrtle’s letters again until April 1934, when she told her mother that he had invited Amice and her to visit him in his new house in the desert. By this time Myrtle knew that he was the botanist and naturalist Francis Wall Oliver (1864–1951), who “[had] the bird sanctuary at Blakeney Harbour” in Norfolk. This was in fact the field station of the Botanical Department of University College, London, which Oliver, Professor of Botany at University College from 1888, had established in 1912 at what is now the Blakeney Point Nature Reserve. Oliver retired from University College in 1929 and was appointed a Professor at the Egyptian University in Cairo, a post he held until 1935.

Professor Oliver had built himself a house on the edge of the desert, about thirty miles west of Alexandria, where he studied the flora and insects of the desert, and it was here that he had invited Amice and Myrtle. Myrtle explained to her mother: “the journey by air was about 130 miles & took about an hour. When we were half way we met armies of clouds coming in from the sea & went up to 7000 ft to be above them. We returned in the evening in under an hour as the wind was with us but there were no clouds so we did not ascend so high. I cannot tell you how much I enjoyed it. We flew over the delta, then over the desert, & over the salt lakes that are on the fringe of the coast. Then coming back by evening we saw all the lights of Cairo below us. The landing was very exciting”. Clearly relations between host and guests had improved from their first meeting in Abydos. A few days later Professor Oliver was one of those giving Myrtle “a lovely send off at Cairo”, bringing her “reading matter & a box of chocolate biscuits”.

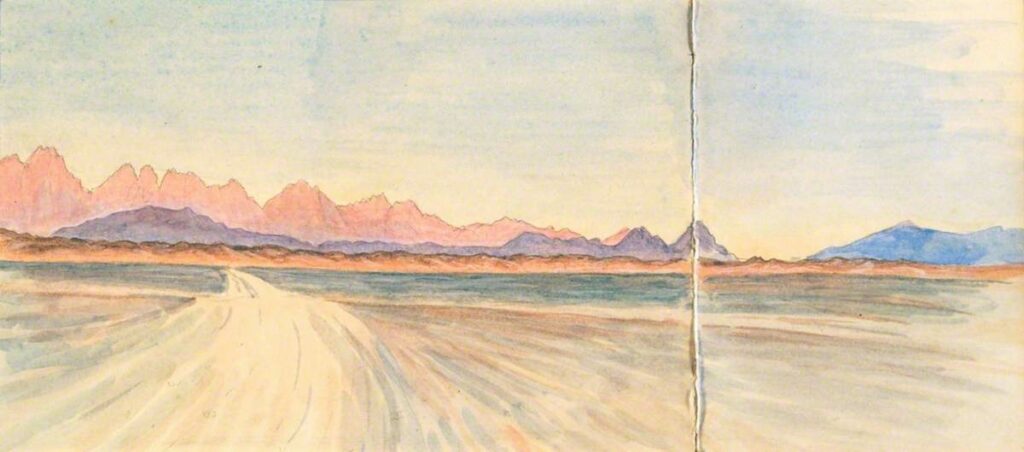

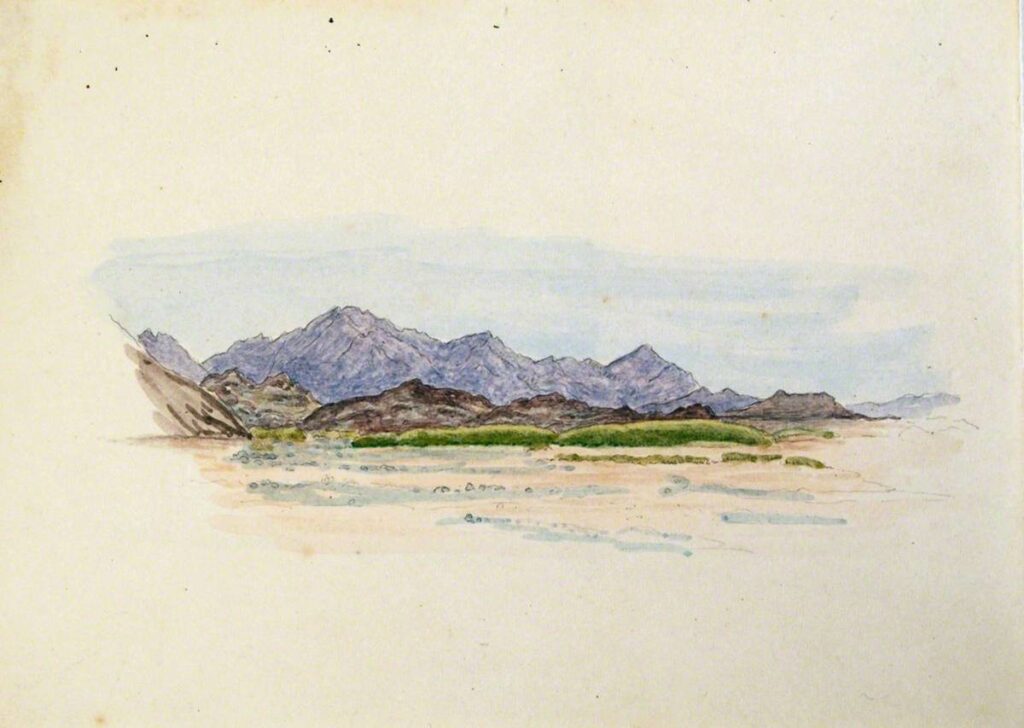

The friendship continued. They exchanged presents at Christmas in 1935, when Professor Oliver gave both Amice and Myrtle books – Myrtle receiving The Nine Tailors and Strong Poison by Dorothy L. Sayers, and Amice, Heath Robinson’s How to live in a flat. Myrtle told her mother that she had “sent the old boy one of Father’s oak ash trays. He is sure to appreciate it”. By May 1937, when she and Amice paid Professor Oliver a final visit at the end of their last season, Myrtle described him to her mother as “our old friend”. She and Amice showed him the sketches they had made as they drove along the Red Sea coast to Suez earlier in their journey. Professor Oliver admired their work, telling the British Egyptologist and botanist Professor Percy E. Newberry in October 1937 that their sketches “were extremely good as records of colour … even of these early studies there were many I would willingly have given £5 apiece for had I been sufficiently affluent”.

© Myrtle Broome (1937?)

Bushey Museum & Art Gallery

© Myrtle Broome (1937?)

Bushey Museum & Art Gallery

By the 1934–1935 season flying was no longer so unusual. Myrtle again travelled to Egypt by boat, telling her mother that at Gibraltar “a German Zeppelin flew over the ship. It was very low & the men in its cabin waved their hats as they passed. It looked very beautiful against the blue sky”, though Myrtle also noted that “it had two black Nazi swastikas on its tail”. Amice met her in Port Said on Monday 29 October, having flown down from Cairo to assist in clearing all the camp equipment through Customs, and they “hoped to catch the return plane to Cairo”. Again, Myrtle does not mention the airline Amice used, but it may have been the Cairo/Port Said service launched by Misr Airwork earlier that year. By autumn 1934 Misr Airwork flew from Cairo to Port Said on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, with flights leaving Cairo airport at 8.10 a.m. and arriving at Port Said at 9.15 a.m. The return flights left Port Said at 3.40 p.m. reaching Cairo airport at 4.40 p.m. A single flight cost PT 175, and a return PT 330. However “it took from 10 o’clock to 2.30 to get it [= the equipment] all cleared”. The usually tolerant Myrtle reported that “unfortunately Amice dawdled the last half hour after driving everybody to work full tilt all the morning & we were too late for the aeroplane, it was a little early returning & not seeing the signal to say there were any passengers for it, it did not descend as usually tickets are taken well in advance”. They had to wait for the 6.30 pm train, and so “instead of being in Cairo by 4.30 we did not arrive until 10.30” leaving Myrtle “feeling a little weary” the following day.

The fantasia staged by the men at Abydos that Christmas reflected the increased prevalence of flight. As usual the performance was a skit featuring a judge hearing cases and giving judgment, and Myrtle told her mother that “an amusing incident was the arrival & departure of the judge by aeroplane. This was managed by him being carried shoulder high round & round the stage & everyone making a buzzing noise”.

In February 1935 Myrtle was expecting a visit from Stephen Sherman and his wife, both of whom had been working with J. D. S. Pendlebury at Amarna. Myrtle told her mother that Sherman “was in the Air Force during the war so Amice wants his opinion on the possibility of a landing ground in our desert here”. As Sherman was born only in 1907, Myrtle must have been mistaken about him serving in the Air Force during the war. However he had taken a short service commission in the Royal Air Force as a pilot officer in 1926, and by the 1930s was a Flying Officer in the Air Force Reserve, so he would nonetheless have been a good person to consult. He and his wife Cleves had married in Italy the previous September; she was the author and artist of Fantastic Fauna: Decorative Animals in Moslem Ceramics, a book of 630 animal drawings copied from Medieval Egyptian crockery and published in 1935. In reviewing this book for The Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society, L. A. Mayer observed with approval that although Cleves’ approach was that of an artist, she had “completely adapted her technique to that of the originals” and had copied the animals “with the accuracy of an archaeologist, a sure hand and a feeling for the brush of the Islamic decorator”. Myrtle and Cleves would no doubt have had plenty to discuss if they compared notes about the challenges of their respective copying projects.

It was around this time that Amice started taking flying lessons, with a view to having a plane at Abydos. According to Janet Leveson Gower’s obituary of Amice in the 1959 in the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Amice was thrilled with her solo flights, but did not complete her training as the Egypt Exploration Society did not support the idea of a plane at Abydos. Her training was not wasted, however. During the Second World War, Amice served as a flying officer in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force. She hoped to use her draughtsmanship, but was posted to Medmenham, where she worked on figures rather than drawing.

Sources:

Letters: 115, 124, 286, 288, 290, 291, 292, 294, 310, 323, 389, 411.

Percy Edward Newberry Collection: NEWB 2/557 (formerly Newberry MSS 1.34/27).

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection and the Francis Wall Oliver correspondence within the Percy Edward Newberry collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for Myrtle Broome’s paintings

- Airline Timetable Images, Björn Larsson, Derek Zekria, and Klaus Vomhof, for information about Misr Airwork timetables and costs

- Salisbury, E. J., “Francis Wall Oliver 1864-1951”, Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society 8/21 (1952), 229–240 [https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbm.1952.0015]

- the Blakeney Area Historical Society, for permission to reproduce the image of Professor Francis Wall Oliver and for information about his connection with the Blakeney Point Nature Reserve (D. J. B White, Blakeney Point and University College London, Glaven Historian 8 (2005))

- University College, London, for information about the Francis Wall Oliver Research Centre at Blakeney Point

- Tony Stead, for the photograph of Stephen Sherman and for information about Stephen Sherman and Cleves Stead

- the Royal Tank Corps Enlistment Records, the Royal Air Force lists, the Western Daily Press & Bristol Mirror, and Ancestry.co.uk, for information about Stephen Sherman and Cleves Stead

- Mayer, L. A., “Review of Stead, Cleves: Fantastic Fauna, with a foreword by Gaston Wiet. Cairo, R. Schindler, 1935”, The Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society 19 (1935), 122

- Gower, Janet Levenson, “Amice Mary Calverley”, The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 45/1 (1959), 85–87. [https://doi.org/10.1177/030751335904500115]

- the Royal Air Force Museum, for information about the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force

- the Royal Air Force Association, for information about Medmenham

- the Artefacts of Excavation project, for information about Percy E. Newberry, John D. S. Pendlebury, and Amarna