Flying – 3

Author: Susan Biddle.

During the 1930s air travel moved from being the preserve of pioneering aviators and the rich to scheduled air services within reach of a wider, though still well-off, public. This post is the third of a series of three looking at Myrtle Broome’s encounters with air travel and, eventually, her own flying experiences. This post focuses on the period from 1935 to 1937, and contrasts Myrtle’s flight from Cairo to Jerusalem with Flinders Petrie’s boat trip forty-five years earlier.

By 1935 flying had become a realistic travel option for Myrtle, though still not routine. At the end of the 1934–1935 season the British archaeologist James Starkey offered Myrtle a fee and all her expenses for a trip to Jerusalem to do some work for him. Starkey was excavating at Tell ed-Duweir, Biblical Lachish, with Olga Tufnell, with whom Myrtle had worked at Qau el-Kebir in her first season in Egypt in 1927.

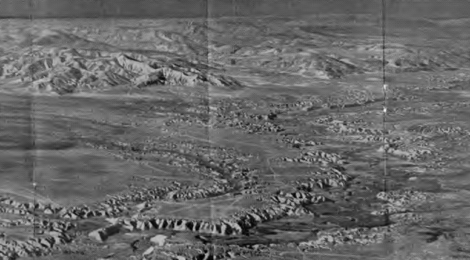

On 10 March 1935, when planning this trip, Myrtle told her mother: “Of course I shall fly from Cairo to Jerusalem”. Concerned that her parents would mind if her return to the United Kingdom was too long delayed, she “even consider[ed] returning Imperial Airways” to the UK. However she concluded that “this would mean a lot of bother about luggage & costs considerably more than my passage money and the portion of the journey from Brindisi to Paris is by rail, so the actual time by air is very short. The entire journey takes three days & nights”. Imperial Airways operated from 1924 until 1939, principally serving British Empire routes, its passengers being usually businessmen and Colonial administrators. By 1935 there were four services a week operating between Egypt and Britain at a cost of £40 for the Alexandria to London leg and £42 if starting from Cairo; two were part of the twice weekly service between London and Australia, and the other two of the twice weekly service between London and Cape Town. The Australia service left Alexandria at 6 a.m. on Wednesdays and Saturdays, arriving at Brindisi (after a stopover in Athens) the same evening in order to catch a sleeper train to Paris leaving at 8.27 p.m. After two nights on the train, they eventually arrived at the Gare de Lyon at 6.40 a.m. on Monday or Friday, in time for a 9.30 a.m. flight from Le Bourget, finally arriving at Croydon at 11.45 a.m. or London at 12.30 p.m. The route and times were the same on the Africa service except that it left Alexandria on Tuesdays and Fridays, and it was possible to fly from Cairo to Alexandria the day before.

Imperial Airways, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

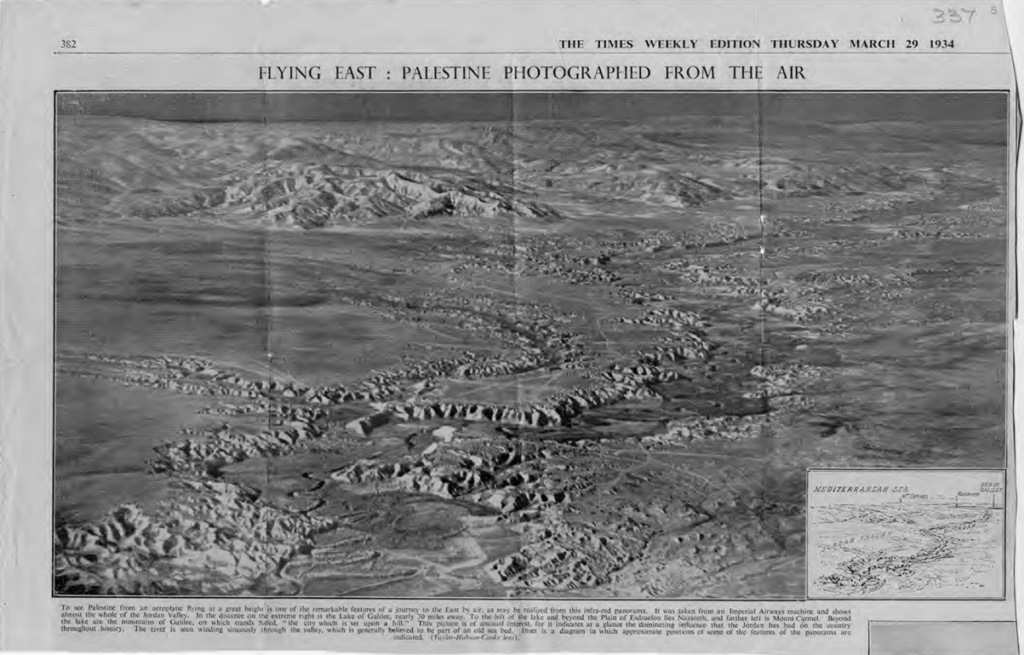

On 19 April 1935 Myrtle enclosed with her letter to her mother an aerial photograph cut from The Times Weekly Edition, 29 March 1934, captioned “Flying East: Palestine Photographed from the Air”, taken by an Imperial Airways aeroplane, to show her mother “what Palestine looks like from the air”. She told her mother that Starkey had “written to say he will meet me at Gaza aerodrome & take me to their camp … and I can go on to Jerusalem by car later”. She was looking forward to the trip, saying to her mother: “doesn’t it all sound thrilling & exciting”.

Myrtle had hoped to travel on Monday 29 April with Cairo Air Ways, but everything had been fully booked because it was the Feast of Sham el-Nessim, an Egyptian national festival held on the Monday following Coptic Easter, celebrated by both Christians and Muslims to mark the start of Spring. She therefore had to delay her departure until Wednesday 1 May, the anniversary of her first flight.

On 2 May 1935 she wrote to her mother from Jerusalem, explaining that she “arrived here by aeroplane yesterday non-stop flight from Cairo Airport to Jerusalem Airport in three hours instead of 15 hours by train”. Forty-five years earlier, British archaeologist W. M. Flinders Petrie had had a much less enjoyable journey to Palestine after finishing his season’s work in the Egyptian Fayoum. He had travelled by boat, leaving Alexandria at 4 p.m. on a Friday in March 1890, quickly encountering “a tolerable wind & rollers before dinner which quite finished my capabilities”. After “a nasty night”, they spent Saturday anchored at Port Said, where Petrie was able to work on board, but they left port just before dinner “and though the storm had gone down there was a heavy swell rolling in, which kept us lively all night, till we anchored at Jaffa at 3.a.m. There was so much sea on, that we bumped heavily against the rocks in the usual anchorage & steam was put on all in a scuffle, & we went & lay further out”. The following day, Sunday, they “all stood anxiously watching the heavy line of breakers in front of the harbour & fully expected that we should have to go on to Beyrut, & take the next steamer back again”. However heavy rain started to fall, calming the sea a little, and shortly after 11 a.m. they “at last saw the boats coming out to meet us. The boats here are large & massive to bear the rough seas; but they could not venture through the usual passage which was a mass of breakers, but came over the sand shoals at a risk of sticking & being swamped”.

Jaffa, before 1899

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Petrie wrote in his journal that “the miseries of the waiting in the boat to leave the ship, & the long row into the harbour (such as it is) in heavy showers are untellable. For 24 hours after it I was shaking inside & out, & even two or three days have hardly put me right again”. In contrast, Myrtle described her journey as “a marvellous experience. We passed over the Suez Canal, it looked like a thin blue ribbon laid out on the desert sands. Then we passed over Sinai, we were 7 thousand feet up, & could see the sea on our left & the mountains of Sinai on the right horizon. It is a pretty big wilderness, but even so the Israelites must have gone round in circles to have taken 40 years to cross it”. Fifteen days later, she flew back to Cairo before embarking from Port Said for the usual voyage back to the UK. As Beatrice, a former general maid, had returned to work for her parents, Myrtle had concluded that they would not mind so much if she was not back until the start of June, so there was no need to fly.

By the start of the 1935–1936 season the shadow cast by the swastika-ed zeppelin Myrtle had seen at Gibraltar during their voyage out at the start of the previous season had intensified. In early October 1935 Italy invaded Ethiopia, and on 7 November Myrtle told her mother that the people in Arabah el-Madfunah were “very afraid the Italians will fly their aeroplanes across Egypt & drop bombs on the way”.

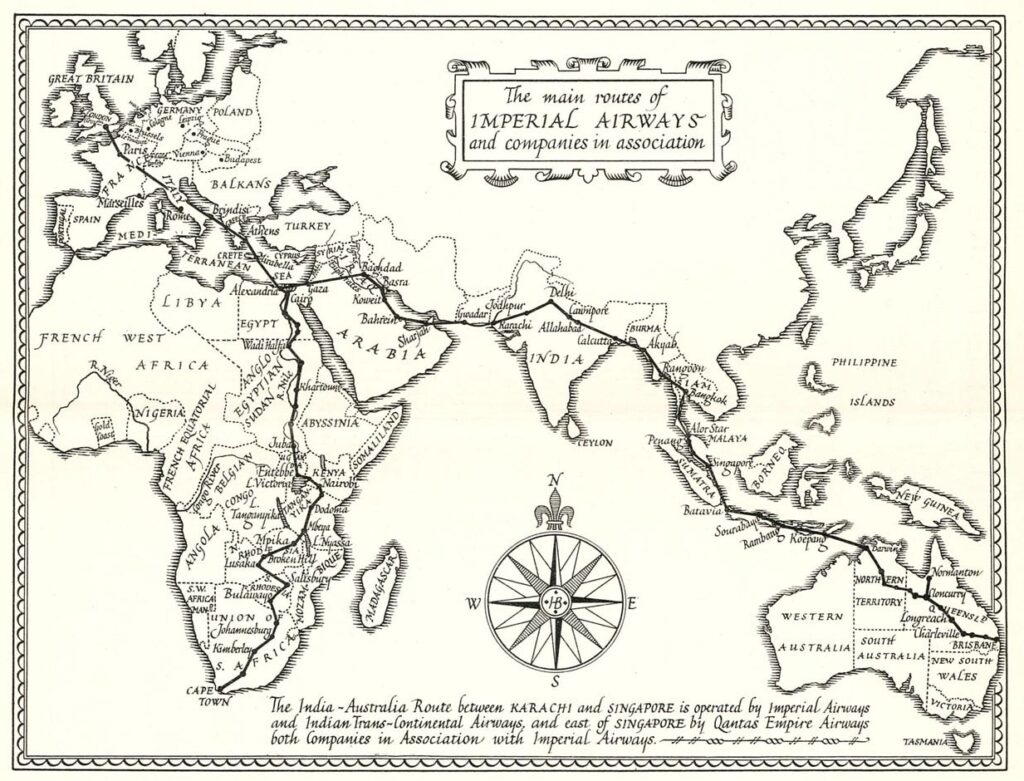

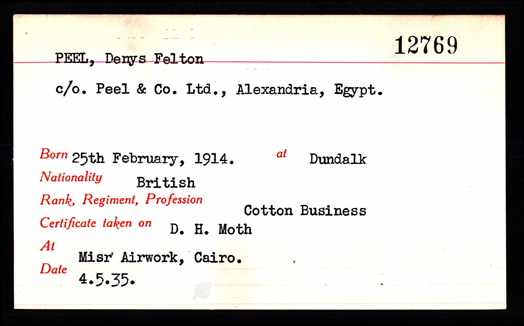

More cheerfully, in December 1935 Myrtle told her mother they had been visited by Denys Peel (1914–2004) who was “the son of the so-called Cotton King” and “such a nice boy, about 22 or 23, a very keen air-man & general all round sports man”.

Photograph from his Royal Aero Club aviator’s certificate

© RAF Museum / Ancestry.co.uk

Denys was helping out at the cotton factory in Sohag while the manager, Charles Oulton, was in a Cairo hospital after a mastoid operation in August. Denys was the son of the Alexandria cotton exporter Digby Robert Peel (1887–1971), and nephew of Sir Edward Townley Peel (1884–1961), who was a leading player in the British community in Alexandria. By the mid-1930s, the family business of Peel & Co. was one of the biggest cotton firms in Alexandria. Earlier in the year Denys had been awarded his pilot’s licence by the Royal Aero Club, flying a de Havilland Moth at Misr Airwork, Cairo.

© RAF Museum / Ancestry.co.uk

He subsequently worked for the Civil Service Air Ministry in Bristol and served in the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve during the Second World War. Unlike his cousin Charles Peel, who also served in the Royal Air Force and died when flying a Spitfire in an air operation over the North Sea in July 1940, Denys survived the war and lived to become High Sheriff of the Isle of Wight in 1981–1982.

Sources:

Letters: 292, 307, 328, 333, 334, 337, 338, 340, 343, 348, 352, 356.

Petrie MSS 1.9 – Petrie Journals 1889–1990, p. 52–54.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection and the Petrie Journals, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Palestine Exploration Fund, for information about James Starkey and Olga Tufnell

- the Penn Museum, for information about excavations at Tell ed-Duweir

- the Artefacts of Excavation project, for information about Qau el-Kebir and W. M. Flinders Petrie

- the Airline Timetable Images, Björn Larsson, and Derek Zekria, for information about Imperial Airways timetables and costs

- the Royal Air Force Museum, London and Ancestry.co.uk, for the photographs of Denys Peel and his Royal Aero Club Aviator’s Certificate

- Bento R. F. and A. C. Fonseca, “A brief history of mastoidectomy”, International Archives of Otorhinolaryngology 17/2 (2013), 168–78 [https://doi.org/10.7162/S1809-97772013000200009]

- the Battle of Britain London Monument, for information about Charles Peel