Learning Arabic – 2

Author: Susan Biddle.

This is the second of a series about Myrtle Broome’s experience of learning Arabic. This post looks at how she progressed during her early lessons and the different techniques she and the schoolmaster used.

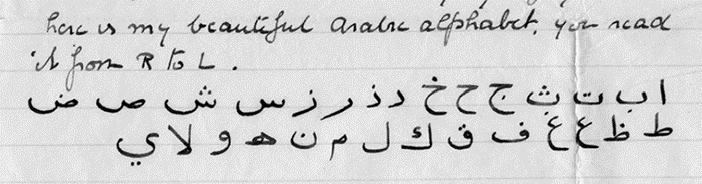

The local schoolteacher who taught Myrtle and, initially, Amice to write Arabic was not used to such diligent pupils. At their second lesson Myrtle “produced my beautifully written out alphabet & he was astonished. He examined it well & pronounced it excellent. Then to my amusement he turned the paper over & told me to write it out from memory in front of him. I do not know if he thought I was playing a schoolboy trick on him. Anyway I wrote it quite successfully”.

Myrtle and Amice had the advantage of artistic skill as well as diligence. Myrtle told her mother their teacher “was amazed at the ease with which we write the Arabic, now that we know how the letters should be formed we can write as well as he can after two lessons. He is not used to teaching pupils who can draw”.

Reading, however, was a different matter. Myrtle admitted to her mother that “we stumble along making the most extraordinary sounds”. Amice described their attempts more graphically – she told Dr. Alan H. Gardiner, editor of the first three volumes of The Temple of Sethos I at Abydos, and his wife that they had “fearful struggles – from the sounds emitted, the effects of an emetic are suggested”. A fortnight later Myrtle confessed to her parents that she was “getting quite a stiff neck through trying to pronounce the gargling sounds”.

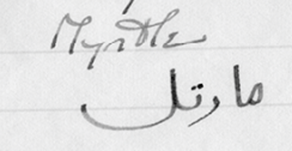

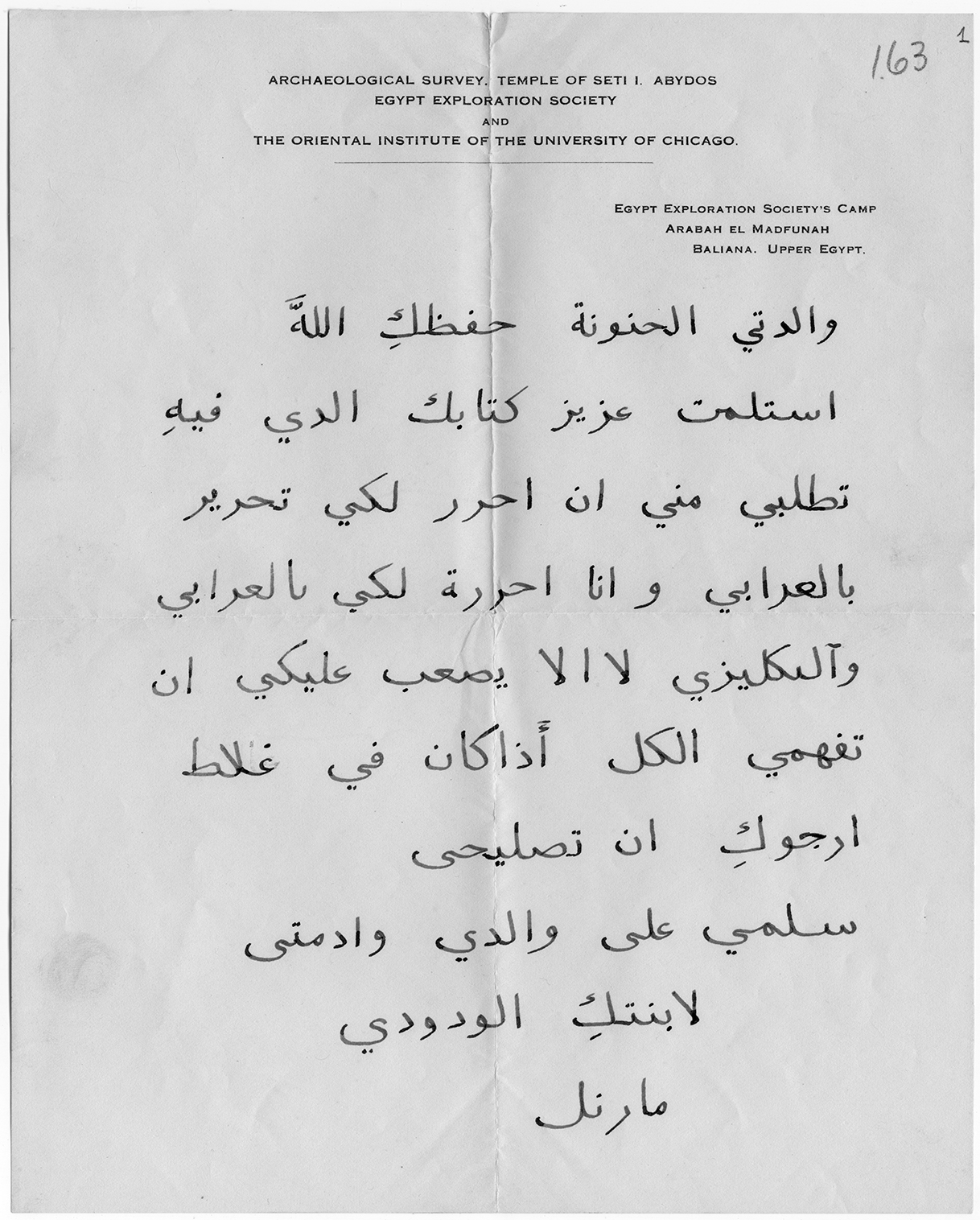

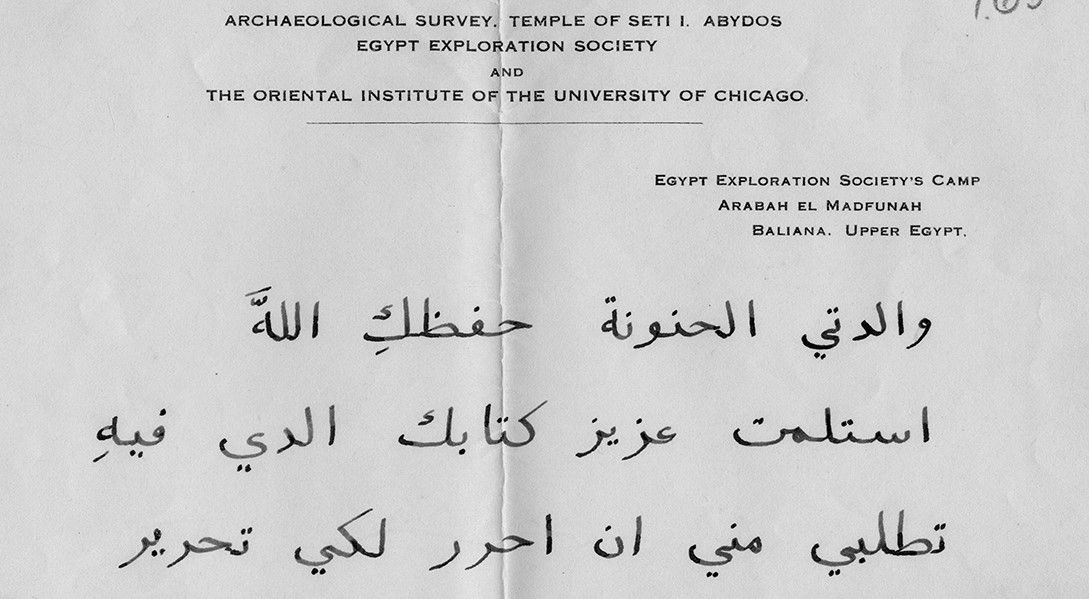

Myrtle and Amice quickly applied their new knowledge. When a parcel arrived from the Baliana station soon after their second lesson, they “were both very proud to be able to make out Baliana written on it”. By mid-December Myrtle was able to write Amice (then in Luxor) a letter entirely in Arabic, admittedly with the help of Nannie, the housekeeper, and she also signed her letter to her mother in Arabic.

Nannie sat in on the early lessons to translate when required, since the schoolmaster spoke no English and sometimes used words and expressions which Amice and Myrtle did not know. However, this was not an unmitigated benefit. Some of the questions Amice & Myrtle asked, such as “why do the letters sometimes lie down flat & sometimes stand on their heads?” made the schoolmaster look worried. He would pour forth “rapid & quite un-understandable technical replies, until he realizes we can’t understand a word of it, & then just shrugs his shoulders & waves his hands & says ‘but either way it is just the same’ or else ‘such a thing is not possible’”. Nannie, who could follow both sides of the conversation, was “convulsed with mirth & has to be rebuked for unseemly giggling in front of the schoolmaster”. Nannie and the schoolmaster frequently argued “because Nannie speaks with the Syrian accent & the schoolmaster speaks the real Bedouin Arabic”. By the end of the season Nannie’s help was less often required for translation, and she no longer joined them, which Myrtle thought was “perhaps just as well, as she and the schoolmaster had the most violent arguments & it only wasted time & didn’t help me much”.

By the end of December 1931 they had “got through the three & four syllable words in the reading book, & are starting on real sentences. We stumble along making noises like a demented menagerie”. In mid-January 1932, Myrtle wrote an entire letter in Arabic to her mother, explaining in her next letter that the last one did not contain much news as it “was a real Arabic one, & a proper Arabic letter only contains compliments & enquiries about health & a few pious phrases”.

At the end of January 1932 Amice and Myrtle started dictation. The schoolmaster, whose name Myrtle had discovered was Sheikh Sarbit, “makes noises & we try to write the signs that the noises are supposed to represent. It’s very exciting”. It was shortly after this that Amice gave up her lessons, leaving Myrtle to persuade Sheikh Sarbit to teach her grammar too. She got him to write out verbs for her so she could learn the different tenses, and at the next lesson “we did verbs & my head began to feel like Brer Rabbit when he got thrown into the bramble bush”. For the following lesson she asked him to give her dictation not by reading from a book but by making up sentences using the verbs she had been learning. This “took some explaining in my limited Arabic but finally he got the idea & went ahead like a steam engine & I struggled to keep up”. She was amused that “he took possession of my india rubber & whenever I made a mistake he promptly rubbed it out”.

By early March 1932 Myrtle was “just beginning to put sentences together with the utmost difficulty. Most of the Arabic I had learnt before was giving the men instructions in connection with the work, & of course those sort of sentences are not very helpful with lessons. I have to hunt up the words I think I shall want & write them down in Arabic & then find out how to pronounce them. I find it very difficult to memorize them”. In April 1935 Myrtle returned to this theme of the difference between the Arabic learnt to give instructions and the Arabic required for proper conversation. That month she made a trip to the Dakhla Oasis accompanied only by Sardic and Ahmed, another of the servants, and enjoyed talking to many of the Egyptians she met, including the marmur [police chief], the omdah [village headman], her guide, and his mother, daughter, and friends.

Myrtle Broome

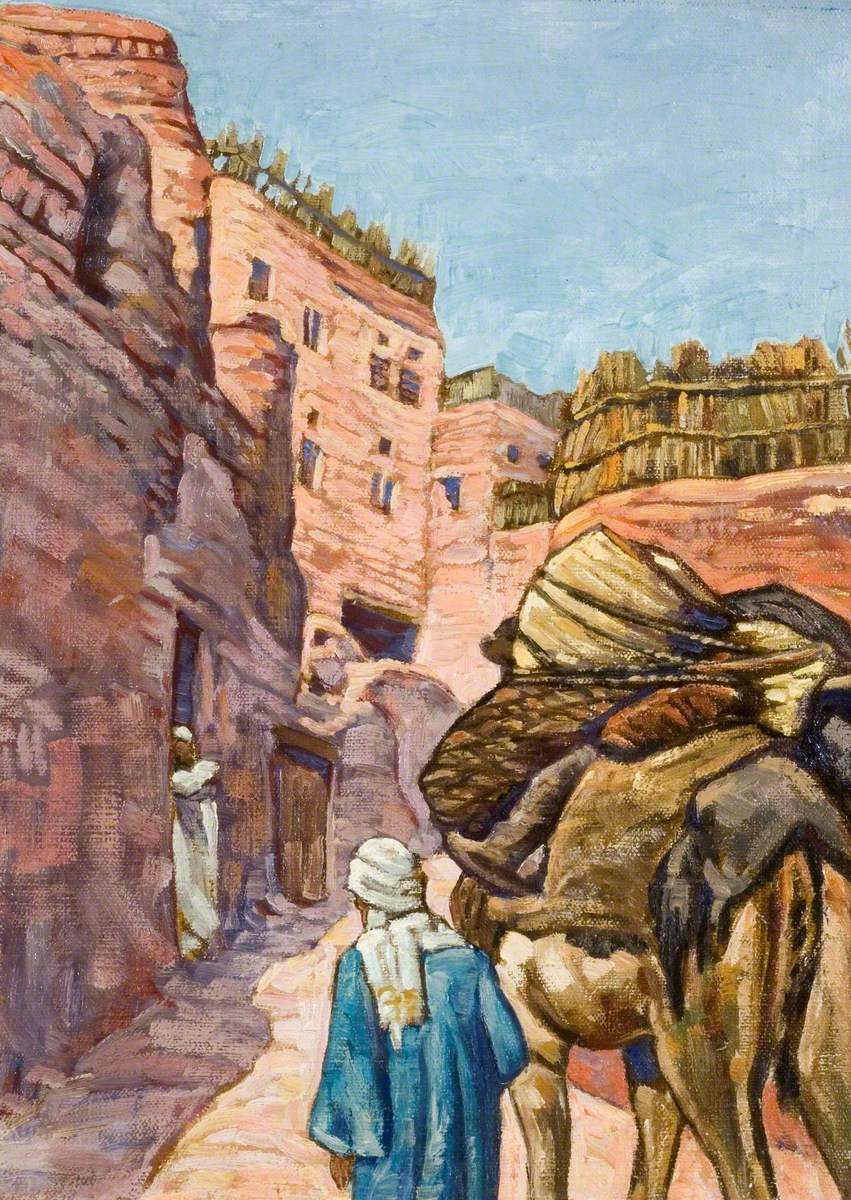

Bushey Museum & Art Gallery: Arab Leading a Camel up a Steep Village Street | Art UK

On her return she explained to her mother: “my efforts to learn Arabic are well repaid, by the friendliness of all the people & their eagerness to show me hospitality. I find so many Europeans only learn enough Arabic to give directions to their servants. They never memorise any form of the verb except the Imperative. Do this – make that – & so on, so though they can make known their wants, they cannot converse, and are regarded by the natives as unfriendly & impolite, but I have made a point of learning the conventional polite replies to the various greetings & this gives them such immense delight that it does not matter a bit if the conversation afterwards gets rather beyond me. A friendly footing is established & we get on together splendidly”.

The benefits of being able to speak Arabic were apparent much earlier, though. In March 1932 Myrtle picnicked in an olive grove belonging to the local omdah [the village headman]. He came to pay his respects to her, and she told her mother: “we had such a long conversation, he was so pleased to hear I was learning to write Arabic … we discussed the merits of modern doctors compared with the doctors of Tut-Ankh-Amen’s time … then we compared the fruits & trees of Egypt with those of England, & altogether had a delightful conversation”.

By that time Myrtle had advanced sufficiently to write stories in Arabic for Sheikh Sarbit to correct. Her English Arabic grammar book contained “some very witty short stories & with the help of a dictionary I was able to transcribe them into Arabic writing”. She was “awfully bucked” when Sheikh Sarbit “read them straight off without a moment’s hesitation & chuckled with appreciation at the joke. Of course there were a number of mistakes, but he thought it a splendid effort”. She was also reading Aesop’s Fables in Arabic, and found these “excellent as I can get the drift of the narrative without having to look up so many words in the dictionary, which takes up so much of my precious time”. Dictionaries were still essential – in March 1932 she spent the equivalent of £1.6.0 on “two fine dictionaries for my Arabic study”.

In dictation, Myrtle had by this time moved on to Arabic proverbs, such as “He who is patient is victorious” and “A good woman is better than golden treasure”. Nannie helped her to translate these but it was “difficult to get the exact shade of meaning in our language”, and Myrtle found Nannie’s explanations “very roundabout & muddly”. She conceded that “of course all this is really far too advanced for me, but Sheikh Sarbit is so thrilled at having a pupil who doesn’t have to be bullied into working that he goes ahead like an express train”. A few weeks later she wrote out some English proverbs in Arabic for Sheikh Sarbit to correct, and wondered what he would make of “Satan finds some mischief for idle hands to do”. She thought the Arabic version, “The head of the lazy one (or idle one) is the house of Satan”, rather neater. She told her mother that it was “great fun writing these in Arabic, because one cannot just translate word for word, but must try to find phrases & words in Arabic that will convey the same idea & sometimes I have to write them two different ways & find out from him which is the best”.

One of the proverbs she translated was “The labourer is worthy of his hire”, which she had chosen in order to be able to “point out the moral when I offered [Sheikh Sarbit] the envelope in which I had discreetly placed the money for my last lot of lessons – but unfortunately when the embarrassing moment came his refusals to accept it were even more profuse & involved than before & I got so bewildered that my beautifully prepared proverb went right out of my head”. She eventually convinced him to take the money by saying “since the good Egyptian government gave him so much money, & provided him with so many things that there was nothing left that he could possibly need, … then would he kindly take the money & buy sweets for the school children; this form of argument was so entirely novel to him that he hadn’t a suitable answer ready. He burst out laughing & pocketed the envelope”.

Sources:

Letters: 153, 154B, 155, 156A, 159, 163, 164, 167, 173, 174, 175, 177, 178, 181, 182, 184, 185, 329, 333.

Gardiner MSS 43 – Calverley Correspondence, Letter 140.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and the Abydos Enterprise correspondence within the Gardiner collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago and The Ancient World Online, for the links to the four published volumes of The Temple of King Sethos I at Abydos

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for Myrtle Broome’s painting

- the Artefacts of Excavation project, for biographical details for Dr Alan H. Gardiner