Nannie

Author: Susan Biddle.

In this post, learn more about “Nannie” — “a dear old soul [who] looks after us splendidly”.

It was in Cairo in October 1929 that Myrtle Broome first met a key member of the Abydos team, their housekeeper Mrs Nellie Maouchy, known to Amice and Myrtle as “Nannie”. Details of Nannie’s background remain sketchy but her character shines through the letters, and the critical part she played in daily life is clear. She was a Syrian lady, old enough to have a daughter in Cairo who in April 1932 became engaged (to a good-looking young Syrian who owned a paint shop and did not require a dowry with his bride, and so was “desirable in every way”).

Photograph by Myrtle Broome (probably 1929)

Bushey Museum & Art Gallery

Nannie prepared the house for the team at the start of the season and supervised the chaotic unpacking of the heavy luggage and equipment which Amice and Myrtle had acquired in Cairo, which was brought from Baliana station on two camels: “all the servants, their relations & friends rushed to help. They all got in each other’s way, they just hawledsic something out. dumped it down anywhere & rushed back again to see what the others had discovered – imagine the confusion. plates & pots & pans, jugs & slop pails – china for the table (& for the floor also) all over the place mixed up with mattresses & pillows & mosquito curtains & bits of packing cases. Everyone talked at once, the dogs barked, the donkeys brayed, the camels grunted & poor old Nannie waved her arms & screamed directions & abuse in fluent Arabic & everyone did their various jobs according to their own ideas on the subject”.

She did the housework and fussed over the Europeans, particularly when they were ill or convalescent. She sent the youngest servant Abdullah to the temple with hot Bovril for Myrtle’s elevenses on cold days. After Myrtle had had a bad cold, Nannie made her drinks of hot lemon and black currant to soothe a tickly cough, and brought her a hot water bottle when she tucked Myrtle up at night.

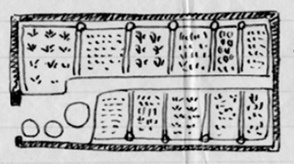

The dig house garden was “the joy of Nannie’s heart”, where she grew both vegetables and flowers.

When the men tried to help in the garden and put their feet in the wrong place, she scolded them vigorously. On one occasion “Ahmud nearly drowned her new cress … & out she flew & turned him out watering pot & all. Old A went off in disgust remarking ‘If a man may’ntsic work he might as well sit down & die’”. In another letter Myrtle reported that the “Garden is flourishing & Nannie is still busy cursing the ants, locusts & Abdullah and other pests”. A resourceful lady, when the police officer came to dinner at a time when they had no flowers, Nannie made a centre piece in one of the fruit bowls, filling it with dried moss decorated with pressed pansies, rose leaves and ferns.

Myrtle spoke a little Arabic from the start but, until she learnt more, Nannie played the vital role of interpreter between Myrtle and the men. While Myrtle was in charge of the camp in Amice’s absence, it was Nannie who translated when Myrtle gave instructions to the men and when she paid them each week, and who helped her take the cook’s accounts.

Nannie was not a natural optimist. In later years Amice and Myrtle took her presents at the start of the season, and Nannie’s reaction to Amice’s gift of two pairs of combinations in 1931 was typical. She said: “they were just what she wanted & the only fault she could find was that when they were worn out she would have got so used to them & would be too poor to replace them & then it would be worse than if she had never had them”.

Although Amice and Myrtle “borrowed” a cook from Dr Junker (Director of the German Archaeological Institute in Cairo) for the first season, in later seasons Nannie also did the cooking. She was clever at stretching meals to provide for surprise visitors – as she often needed to be. When Sir Robert and Lady Greg unexpectedly came to lunch, she had to make two pigeons feed four people at short notice – “as usual she arose to the occasion & served omelettes first, & then lots of fried potatoes & various vegetables with the pigeons, & a nice fruit salad with cream to follow. So altogether we did not do so badly”.

Photograph by Walter Stoneman (1930)

National Portrait Gallery; licence

https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/use-this-image/?email=smbiddle15%40gmail.com&form=cc&mkey=mw222643

Her cooking was usually successful – we hear about stewed chicken with rosemary, chicken pie, crystallised orange and mandarin skins, lemonade made with a gift of lemons, caramel custard, “glorious apple pies with cream”, marrow fried in butter, “a delicious soup [made] with the young pea pods” when grubs destroyed the stems and barley broth. Nannie also tackled traditional English dishes such as cauliflower cheese, treacle tart, apricot jelly and force meat balls for which she had to use fat instead of suet, as well as various cakes. On at least one occasion, however, things did not turn out so well – for dessert one evening, Nannie served gooseberry fool, but made with mayonnaise instead of custard! She shamelessly blamed the youngest servant, Abdullah, for this, saying he knocked over the bottle of mayonnaise which got in somehow. Unsurprisingly, Amice and Myrtle were not convinced and “suggested that no excuse is better than some”.

For all this, Nannie was paid E£6 per month, with a monthly retainer of E£3 for the period when the team was not at Abydos.

Sources: letters 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 39, 55A, 56, 57, 79, 97, 117, 121, 144, 207, 216, 235, 267, 310, 351, 383, 395, 396, 399.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Myrtle’s letters and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Egypt Exploration Society, for access to their Amice Calverley Archive

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for copies of photographs from their Myrtle Broome Collection

- the Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge, for information about Sir Robert Greg

- the Digital Giza project, for the image of Hermann Junker