Police – 1: The local police officer

Author: Susan Biddle.

This post looks at Myrtle Broome’s dealings with the local police in Arabah el-Madfunah.

Myrtle Broome and Amice Calverley had frequent contact with the local police officer in Arabah el-Madfunah. The services provided by the police were many and various, but rarely involved anything criminal.

Their most frequent contact was social and often involved a meal. A week after arriving in Abydos for her first season, on 21 October 1929, Myrtle and Amice “went to tea with the police officer at Arabah el-Madfunah. He is a very young officer, rather shy & self-conscious but most polite and anxious to be friendly. He gave us a very nice tea, with bread, butter, jam, cheese, biscuits, melon & grapes, & entertained us with Arabic records on his gramophone”. They returned hospitality a week later when the police officer came to dinner. Myrtle told her mother that “he has not long left the military school. He speaks English very well but has to think his sentences out carefully & we have to speak slowly & distinctly”. She thought he enjoyed the dinner party: “we had soup, roast turkey, potatoes & beans, caramel custard, watermelon & pomegranates & coffee”.

In the course of the eight seasons, a series of different police officers were posted to Arabah el-Madfunah, and the cordiality of relations varied. In December 1932 there was “a new police officer who is rather a bumptious young man”. On 9 December this police officer “came in [to the temple] with two young Egyptians of the student class, they behaved abominably, laughing & making lewd remarks about the reliefs. One of our temple guards, our old friend Ali Azib, asked them to show their antiquity tickets or permits as of course was his duty. They hadn’t either, & one of them hit him across the face. Naturally he resented it, but fortunately kept his temper & did not hit back, but there was an awful rumpus”.

A few days later they had a visit from the new Inspector of Antiquities, who enquired about the incident and “insisted on the police officer apologizing to Ali Azib”. The team was “all very glad about it as we do not like this new police officer at all. He comes in bothering us with questions & invitations at all sorts of times & will not take a refusal but asks why-why-why all the time. We call him the camel fly because he is unsquashable”. The inspector’s lesson seems to have been a salutary one as Myrtle was able to report to her mother in January 1933 that “there has been a distinct improvement in the manners of our police officer, I think someone (possibly his superior officer in Baliana) has told him we are people of great importance & friends of high officials in Cairo & must not be treated with familiarity as if we were American tourists, for when ever he comes into the temple now he apologizes for his presence & hopes he isn’t bothering us. He is rather like a tiresome puppy that one has had to smack, that lies on its back with all legs in the air & begs to be forgiven. One would like to pat it, but one knows it is quite ready to be tiresome again if one is the least bit friendly”.

The successor to the “camel fly” was a Copt called Messiah who “speaks quite good English & has been in the Customs at Port Said”. On Christmas morning 1934 he presented them with an enormous bunch of roses, before returning that afternoon to see the Christmas tree and join them for tea. Unlike the “camel fly” he was “polite & pleasant & does not presume at all”, so they could “invite him to our festivities without being afraid he will expect us to dine with him the next week”. He brought them more roses as a parting gift when he was transferred to another outpost in April 1935.

In December 1936 “the camel fly” was posted back to Arabah el-Madfunah. He called on them one evening, and Myrtle told her mother that “he is as bumptious as ever & we thought we were never going to get rid of him, our bath water got cold & our supper was ruined by being kept hot for us, the broadest hints did not have the slightest effect, we shall have to become hareemly unapproachable”. However this seems to have been due at least in part to the excitement of reunion, since by January 1937 Myrtle and Amice were “very glad to find that the police officer whom we had nicknamed the camel fly is a reformed character & has ceased to pester us so that we can be pleasantly polite without being afraid of endless invitations to tea”. The reform was more than skin-deep – later that month she told her mother that “he has really behaved so nicely this time that we had him to lunch with us one day in the temple, (it was quite suitable as we had our male staff to assist in the entertainment). We gave him an English lunch and felt obliged to accept when he invited us to an Egyptian luncheon with him the following day”. This turned out to be a nine-course feast as a result of which Amice “got bad indigestion and had to resort to a dose of eppy [Epsom Salts]”.

Photograph by Myrtle Broome(?) (date unknown)

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Crime was rarely a problem. There was one “exciting incident” in November 1933 when Myrtle and Charles Little, who had joined the team part way through the first season, visited a local Sheikh at the holy tomb of one of his ancestors. For this excursion, Myrtle and Charles rode camels and were escorted by one of their Sudanese guards on a donkey and by most of their servants, also on donkeys, who had also wanted to visit the tomb. As they rode home, “two men in a field by the road were having an altercation & one drew a knife & was going to attack the other when our Soudani jumped off his donkey & slashed at him with his long hide whip & cut the knife out of his hand in time. Unfortunately the man escaped before Mahommed Kheir [the Sudanese guard] could seize him, but he got the knife & got a statement from the other man & reported the affair at the police station at Arabah. Of course all our men were in a state of wild excitement & told everyone we met on the road all about it”.

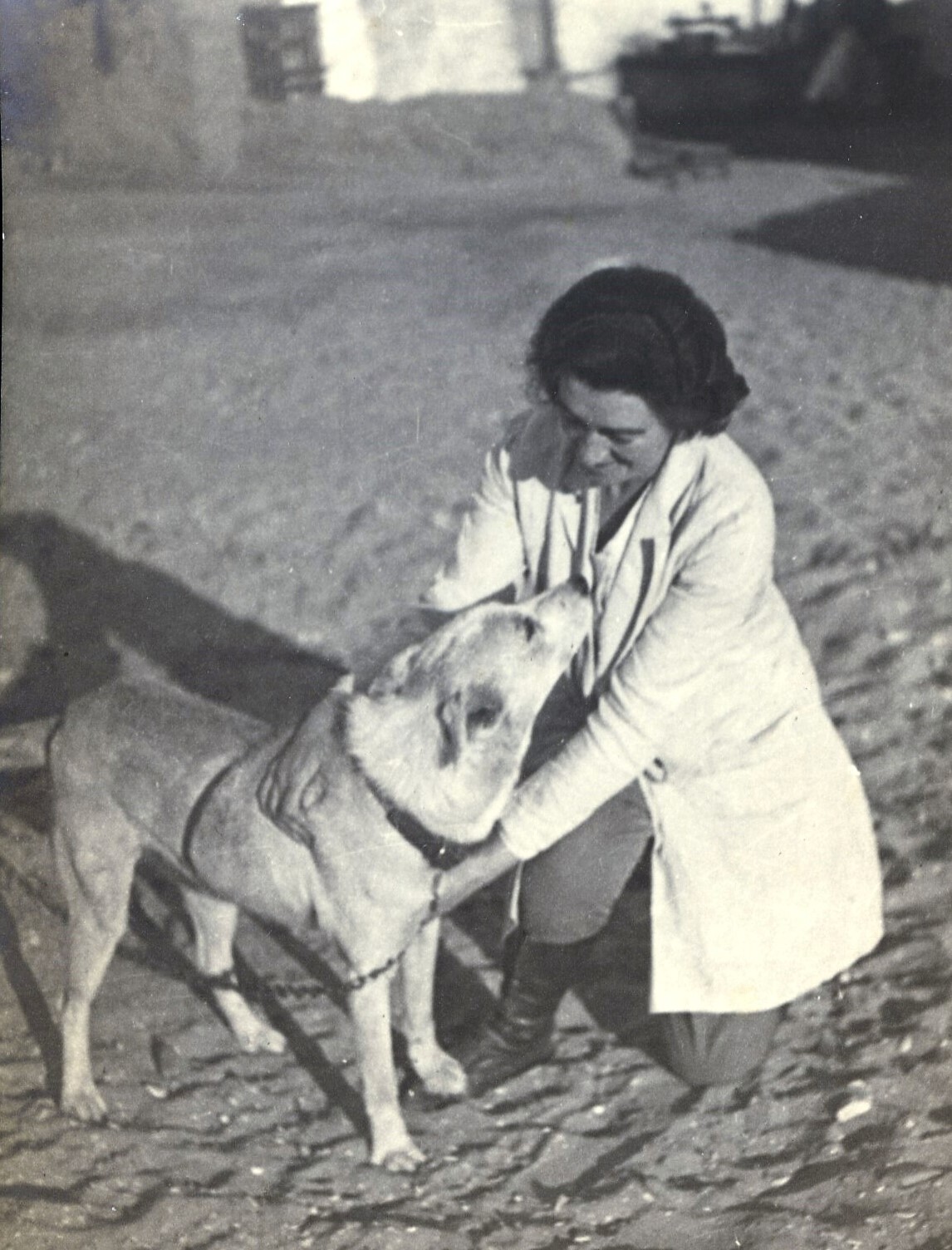

Other dealings with the police that month were sadder. The police put poisoned meat down in the market place to control stray dogs, and both the much-loved camp dog, Wip-Wat, and the dog belonging to Abdullah, one of their servants, were inadvertently poisoned and died.

Photography by Amice Calverley(?) (date unknown)

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

The children dragged the bodies of the many dead dogs into the desert, where they were left to rot in the sun. As a result, Amice and Myrtle were “beginning to notice a bit of a whiff”. Myrtle “wrote to the omdah – in my best Arabic & told him we were being annoyed by the foul smell & would he kindly give an order for all the dead dogs to be buried”. The omdah, the headman of the village, dealt with the problem promptly, so Myrtle did not need to raise it at police headquarters at Baliana which would have been her next step.

Even sadder was the incident in November 1935, following the Italian invasion of Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) in early October. Myrtle told her mother that “the children of the village were playing a war game, & one side were Abyssinians & the other Italians, & the Abyssinian general whacked the Italian general over the head & killed him, & when the boy was taken to the police court he kept saying ‘it does not matter because he was an Italian’”.

In April 1935 the local police officer helped Myrtle resolve a dispute with a tailor in the nearby town of Baliana. Myrtle had commissioned the tailor to make her a “dust coat” from a piece of handwoven material – “a cotton & silk mixture in pale sandy colour” – that she had bought during a holiday trip to the Dakhla Oasis the previous month. Presumably this was for driving – though going out of fashion as cars became enclosed, a dust coat was probably a sensible precaution when driving an open car in the desert. The dust coat was delivered on time and was “beautifully made, but the getting & the paying for it was rather dramatic, the man demanded double the proper price & was insolent as well”. Myrtle refused to negotiate and “referred the matter to the chief of police in Baliana who is very courteous to us on all occasions. He dealt with the matter in the real Oriental way, sent some soldiers to the tailor’s shop, they brought the tailor & the coat to the police station. He was there given the correct sum that he had refused to accept & told to mend his manners”.

From the collection of the Western Illinois Museum

The police officer was also called on for help in the case of accidents. When a patient with a burnt arm refused to go to the hospital in Sohag for treatment, Amice “sent a message to our local police officer & he came along the same afternoon, so she reported the case to him & asked him to see that the poor old man was sent to the hospital & properly treated”. When Otto Daum, who joined the team in 1934 to copy scenes and texts, broke his leg and wrist very badly in an accident at the temple in December 1935, Myrtle “sent Sardic to the local police station to telephone to the police headquarters in Baliana (the police are connected by telephone) to have a car sent immediately to take him into hospital”. The ambulance arrived with the police doctor and the local police officer, as well as a hospital doctor and two attendants, and “the police officer wrote out a lengthy account of the accident”. When Myrtle had finally seen Otto off on the overnight train to Cairo for treatment there, it was the local police officer who “ordered a taxi for [her] & sent a soldier to escort [her]” back to camp. Myrtle told her mother that “the police … were simply splendid”. She had earlier told her mother that this season’s police officer was a very shy young man, but he certainly came up trumps in this moment of crisis.

Amice and Myrtle invited this police officer to lunch on Christmas Day 1935, for which he showed his appreciation in an imaginative way. On Christmas Eve he “had fixed up his little radio set in our Teresina so that we might hear the London programme which was relayed from Cairo on Xmas Day. Wasn’t it a nice thought of his, we heard a variety of Arabic and English music to the accompaniment of what sounded like a thunderstorm or artillery practice. Amice regarded it with horror & retired to the innermost recesses of her room as soon as politeness permitted, but Nannie [the housekeeper] & the men loved it”. Myrtle “sat out in the Teresina & listened to it also because I thought it was so kind of the man to send it to us & I wanted him to feel that it was appreciated”.

Sources:

Letters: 33, 34, 86, 125, 197, 200, 204, 243, 244, 304, 309, 334, 335, 336, 348, 358, 359, 362, 394.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for the photographs from their Myrtle Broome collection

- the Western Illinois Museum, for the details and image of motoring dusters