Police – 2: The frontier police and senior police officers

Author: Susan Biddle.

This post looks at Myrtle Broome’s dealings with the frontier police and with the higher ranks of the police force.

Each season Myrtle, sometimes with Amice Calverley but always with the head servant Sardic, enjoyed at least one holiday “trek” to another part of Egypt. Police approval for these expeditions was always required, and the police were nearly always very helpful.

In February 1929 Myrtle and Amice prepared for a trip by camel to the Kharga Oasis, 120 miles away in the Western Desert.

For this they had to “hire camels who are trained to drink once in three days or so, ordinary village camels who are used to being watered every day are no use for this trip”. Sardic introduced them to the men who made the journey transporting green dates, who offered to provide them with seven desert-going camels. They also needed proper saddles – those they had used for a day trip to Nag Hammadi “were only pack saddles & not suitable for a long trek”. Initially the inspector of police“promised to lend us proper saddles belonging to the police force, also special skins for carrying our water supply”. Myrtle explained to her mother that the ordinary pack saddles had “two poles covered with grass matting, with padding underneath to fit the hump” and were “not exactly easy or comfortable to sit on for long”.

However, the offer of the police camel saddles was withdrawn, ostensibly because a local village where there had recently been a fight was “giving trouble again, & the police may have to go out in force”. Myrtle told her mother that “we have good reason to believe this … was a ruse to stop us. He thought we would not go without the proper saddles … the excuse about the turbulent village was mostly bunkum as camels wouldn’t be used in a local rising”.

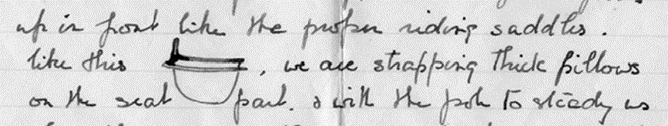

Undeterred, they “got the village carpenter to convert 3 pack saddles into riding saddles”. The carpenter “fixed poles up in front like the proper riding saddles”, Myrtle and Amice then “strapp[ed] thick pillows on the seat part”, and Myrtle expected that “with the pole to steady us when the camel sets down & gets up we ought to be quite comfortable”.

In mid-February 1930 Myrtle reported to her mother that “our Kharga trip was a great success. … The people here, including the local police, were scared stiff at our undertaking, but we have carried it through in spite of many warnings … We have trekked 130 miles across waterless desert in 4 days, average speed with pack camels 2¾ to 3 miles per hour”. One can understand why the police were nervous though; their guide, Abdu Jouat, told Myrtle and Amice that “as far as he knows we are the first Europeans to take the old camel trail for 25 years, & never has he known or heard of solitary women attempting it as we did” – though their entourage of Egyptians meant Myrtle and Amice were hardly “solitary”.

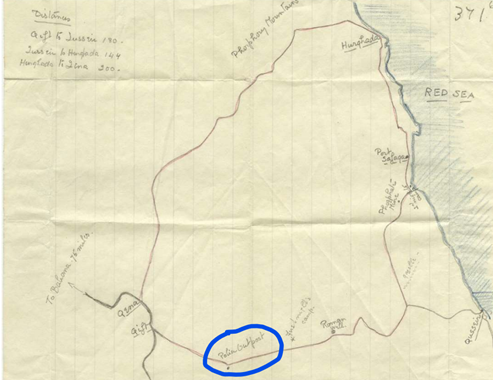

Myrtle returned to the Kharga Oasis on her own in 1935 when she continued on to the Dakhla Oasis, this time travelling by train to Kharga and on to Dakhla by local lorry. She explained to her mother on 5 March that “there are various formalities to be gone through, as I have to inform the police & they send instructions to the police in the Oasis, & I shall have to report at the Markaz [local administrative centre] on my arrival”. In her next letter on 10 March, she reported that “the Mudir [governor] of Sohag has got in touch with the Frontier Police of the Western Desert & they say it will be quite all right for me to go out there & they will assist me in any way they can”.

All went well, and on the return leg of her journey Myrtle had time for an excursion to the villages of Bulaq and Beris, about 100 miles south of Kharga. She sent a letter by hand of Sardic to the marmur of the Kharga police [similar in rank to a major] to tell him her plan, and “Sardic returned with a letter for me to give to the ombashi [corporal] in charge of the police outpost in Beris where I should have to pass that night”. She told her mother that “The police outpost consisted of four whitewashed rooms of mud brick, three for the men’s use & the other kept for the Police Officers going their rounds, government officials & privileged travellers. It contained two camp beds, a camp chair, a washstand & a strip of matting. Bedding consisted of a mattress, a hard bolster sort of pillow & a blanket, & a mosquito curtain. Everything clean & in good order. There was a nice little garden & a place where the camels were tethered”. The ombashi “was overwhelmed at having to entertain an English lady, he had never had to do such a thing before, his eagerness to serve me was almost embarrassing. He wanted to act as lady’s maid”.It was only when Myrtle said that she wished to change her clothes that the ombashi withdrew so she could have a proper wash.

In March 1936 and 1937 Amice and Myrtle made trips to the Red Sea in Amice’s Jowett car, Joey.

Myrtle Broome

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Before crossing the Eastern Desert, Myrtle and Amice similarly had to check in with the frontier police for their equipment to be inspected and to confirm their route. These police would send a telegram – at Amice and Myrtle’s expense – to notify the police at Hurghada to expect them. They also had to report to the Hurghada police on arrival, and to report their return to the frontier police at Qena.

Letter 371, page 6

This was as much for Amice and Myrtle’s own protection as anything else. In March 1937 Amice and Myrtle enjoyed the desert journey to the Red Sea so much, and stopped so often to sketch, that they “spent over two days on the journey & when we arrived at Hurghada we found the authorities getting anxious about us, if we had been much later they were going to send the government lorry out to search for us”. The police were “very anxious about people delaying on the way [but] when they saw how we were equipped & prepared for emergency they realised we were experienced in desert travel & said it would be quite all right if we wished to explore tracks off the regular route on our return so long as we advised them of our intentions & reported our arrival at Qena”. After camping for two nights on their return journey, they arrived at the Qena frontier police outpost after 7 p.m. and were grateful to have “a letter from the governor of the Red Sea Coast to the sergeant in charge telling him to give us the Rest House for the night & generally look after us”.

Myrtle and Amice also had occasional contact with more senior members of the police force. In January 1937 they gave a lunch party in the temple for the mudir of the province and the chief of police. Myrtle told her mother that “the mudir speaks very good English but the chief of police was not so fluent and had to be helped out occasionally with a little Arabic”. The menu included turkey, cauliflower with cheese sauce, apricot jelly & cream, and treacle tart which “was new to them. They attacked it with knife & fork in the most business like way & approved of it”. The lunch party had been arranged during a visit by Amice’s cousin Jan “so that she might have the opportunity of meeting some of the upper class Egyptians”. Jan was very interested in all Amice and Myrtle could show her, not just the temple and antiquities, but also the desert and local life. Jan had previously “been staying with her brother (army) and his wife in Cairo & their only idea of entertaining her is to take her to cocktail parties & to watch tennis & polo at the club – which is rather disappointing for an intellectual guest in Egypt for the first time”.

Photograph by Myrtle Broome(?) (date unknown)

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

The following month Myrtle and Amice “had Russell Pasha & his wife to lunch in the temple, they were very pleasant. He is a very important person out here, having been chief of Police in Cairo for some years. I expect you have seen his name in the papers when there have been riots in Cairo”. Sir Thomas Wentworth Russell (1879–1954), known as Russell Pasha, was the commandant of the Cairo city police. He had entered the Egyptian service in 1902, serving first with the Alexandria coastguards and then as inspector in every Egyptian province, directing police activities including dealing with the consequences of Nile floods and plague epidemics. He had been the motivating force behind the formation of the police camel corps in 1906. In 1911 he was appointed assistant commandant of police in Alexandria, in which capacity he dealt with city demonstrations and gambling dens as well as leading anti-contraband operations in the Western Desert. He was transferred to Cairo as assistant-commandant of the city police in 1913, becoming commandant in 1917. After the First World War he focussed on fighting the spread of drugs, particularly heroin and cocaine, and drug addiction, and in 1929 had become the first director of the Egyptian Central Narcotics Intelligence Bureau.

Myrtle and Amice even had dealings with C.I.D. During Myrtle’s first season, Alfred Lucas (1867–1945) took time out from his work conserving the artefacts from Tutankhamun’s tomb to visit the team in Abydos for five days in December 1929 in order to advise on cleaning the painted temple walls.

Alfred Lucas (seated) with Arthur Mace (standing) working outside the “laboratory” set up in the tomb of Seti II, stabilizing the surface of one of Tutankhamun’s state chariots

Photograph by Harry Burton (p0517)

© Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

Myrtle told her mother that Lucas “is a nice man. It is an awful feather in our cap to get him out here as he is quite a famous analytical chemist, he has worked a lot for the C.I.D & has helped detect a number of criminals”. Trained as an analytical chemist, Alfred Lucas had gone to Egypt for health reasons in 1897, and in 1912 had become director of the Government Analytical Laboratories and Assay Office. In this capacity he acted as an expert witness in criminal trials involving firearms and forgeries, earning a reputation as a specialist in ballistics and handwriting. The main English language newspaper in Egypt at the time, The Egyptian Gazette, nicknamed him “Egypt’s Sherlock Holmes”. On retiring in 1923, Lucas had become the Chemist to the Department of Antiquities, which in December 1922 had “lent” him to Howard Carter to work on the cleaning and conservation of objects from Tutankhamun’s tomb. Myrtle told her father that Mr Lucas “seemed to enjoy himself trying all sorts of methods for getting the layer of dirt off the walls without removing the paint underneath, some of my fine sand paper came in useful in parts”.

Sources:

Letters: 44, 45, 52, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 327, 328, 330, 370, 371, 373, 394, 395, 398, 401, 403.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for the photograph and painting from their Myrtle Broome collection

- the Artefacts of Excavation project, for biographical details for Alfred Lucas and Howard Carter

- Steven Luscombe, for information about Sir Thomas Wentworth Russell, in his article: Luscombe, S., “The Road to Suez – Sir Thomas Wentworth Russell”, The British Empire 2022 [accessed 9 September 2022]

- Information on Alfred Lucas from: Brunton, G., “Alfred Lucas 1867–1945”, Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 47 (1947): 1–6; Edwin, H. H., “Alfred Lucas. O.B.E, F.R.I.C, F.S.A.”, Bulletin de l’Institut d’Égypte 28 (1945): 163-165; Gilberg, M. “Alfred Lucas: Egypt’s Sherlock Holmes”, Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 36.1 (1999): 31–48