Shoes and clothes – 4

Author: Susan Biddle.

This post is the fourth in a series looking at clothing. This instalment focuses on the clothes worn by Myrtle Broome and Amice Calverley for more formal occasions, and also deals with the costumes of their tourist visitors and some of those whom Myrtle met on her travels.

Myrtle usually travelled first class on her voyages to and from Egypt, which required some smart evening wear. In September 1929, in the Atlantic en route for her first season at Abydos, Myrtle told her mother that for dinner on board the S.S. Ranpura “So far I have worn my black with my red shawl, but when we get into the Mediterranean I shall sport my new blue. My necklace also appears in public in the evening”. By the time they approached the Egyptian coast she could report: “I have been wearing my blue dress for dinner the last two evenings, it is very nice to dance in. My shawl is very useful”. On the voyage out in 1934 on board the S.S. Tuscania, she asked her mother to “Tell Father my silver shawl has been very useful, it has made my two last year evening frocks look quite smart”.

In October 1931 Myrtle’s fellow passengers on the S.S. California included a maharajah and his suite who “all wear conventional evening dress” for dinner. She told her mother that during the evening dancing on deck, one of her partners was “an Indian from the Maharajah’s party” who “danced beautifully. He was very tall & slinky”. She herself wore a black satin coat in the evenings but it was so warm that year she was glad to take it off in the dining saloon. On board the S.S. California again three years later, Myrtle admired some Indian ladies who “wear their native costume, wonderful patterned silks with the most marvellous borders, gold embroidery & sequins etc”. Her fellow passengers on that voyage also included some British soldiers whose “red mess jackets look very cheery in the dining saloon”.

Myrtle and Amice did quite a lot of socialising when in Cairo or Alexandria at the start and end of the season. At the start of her first season Myrtle wrote to Eric, a friend in England, that on arrival in Cairo she was immediately “drawn into the social whirl. I went to the consulate & was presented to the British Consul, had several teas at Gezira Sporting Club, saw a thrilling game of pelota … went to several luncheon & dinner parties & aired all my best frocks”. She told her mother that, in preparation for her visit to the Gezira Sporting Club, she had bought “a pair of silk stockings to go with my crepe-de-chine frock as the ones I had were all too pinkish, & I wanted to be very swish as we were having tea at the Sporting Club which is the smartest gathering place in Cairo”.

Photograph by Jorge Lascar (2012)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gezira_Sporting_Club_(14609292100).jpg

In November 1931 she reported to her mother that Professor Percy Newberry “insisted on our going to dinner with him at the Continental (a swagger hotel next to Shepheard’s)” when they were briefly in Cairo en route to Baliana. The Continental-Savoy, like the Shepheard’s, was a social hub for Europeans in Cairo; it was here that Lord Carnavon had stayed, and died in 1923. At the end of that season Myrtle and Amice spent a few days in Cairo before embarking on their ship as they had so many invitations. These included an invitation for lunch at the Residency with Lady Loraine, wife of Sir Percy Lyham Loraine, the British High Commissioner for Egypt and the Sudan. Lady Loraine had visited the Temple of Seti in January that year and Amice had called on her when staying in Cairo in March; Amice had returned from that visit armed with both “an enormous box of chocolates” and an invitation for both Myrtle and herself to call when they were in Cairo.

At the end of their final season Amice and Myrtle stayed in Alexandria with Emmeline, Lady Barker, the mother of one of Amice’s friends. The Barkers moved in the highest social circles in Alexandria. Emmeline’s husband, Sir Henry Barker, was the head of the British community, President of the British Chamber of Commerce, and a director of a range of companies including the National Bank of Egypt, the Alexandria Water Company (established by Emmeline’s father), and Marconi of Egypt. Unsurprisingly, Myrtle reported to her mother that they had “been entertained royally, taken to the races, to watch polo, to their hut on the shore for tea etc”.

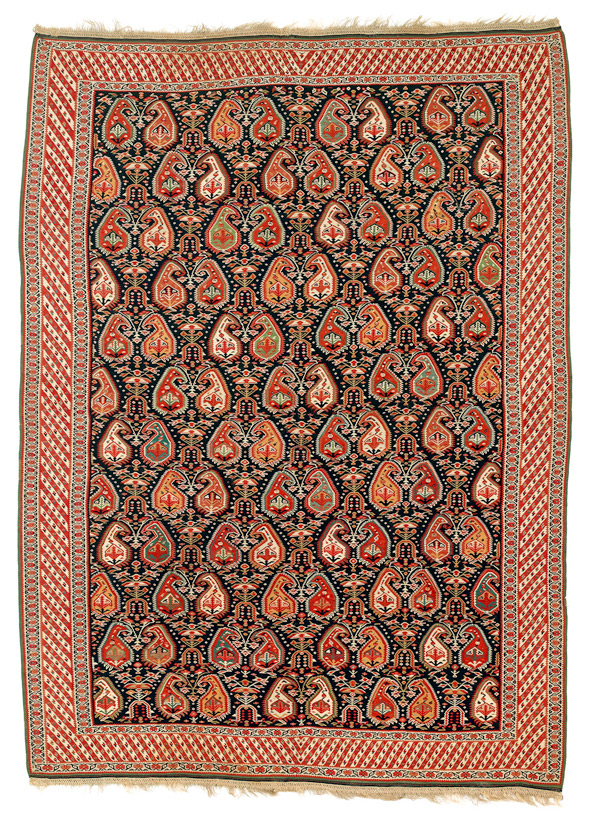

Smart dresses were also needed for evening socialising during the working season in Abydos. In January 1930 Myrtle and Amice were invited to dinner on one of the big Nile steamers by a friend, Major Anderson, and his fellow traveller General Gordon. Myrtle told her mother that she and Amice “accepted with great joy, poshed up in pretty frocks & powdered our noses & set off” for what Myrtle described as “a very jolly time”, including “a lovely dinner with red wine and all trimmings”. In February 1934 Amice and Myrtle ordered seven metres of “a wonderful white satin with a Persian design of pine cones & flowers woven in, in all gay colours” to be made for them by an Egyptian silk weaver, which would “make us each a gorgeous dinner jacket”. The Persian pine-cone design Myrtle mentions was probably the “boteh”, a pine cone-shaped motif with a curved end which in Europe is known as “paisley”.

Unknown Sehna artisans. Photograph by auctioneer (?)

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Sadly, in April that year Myrtle reported that the silk weaver had “only made one small item of the order we gave him & hasn’t even started the things we specially wanted. We are full of rage & indignation”. There is no reference in the subsequent season to the satin being delivered, so it seems they had to do without those dinner jackets. Amice of course needed a similarly smart wardrobe. In January 1930 she recycled “the remains of a cream satin evening dress” to make the local Coptic priest “a very fine cover for his reading desk”, embroidering the cover with a large Coptic cross in apricot silk.

At the end of the sixth season Myrtle spent three weeks in Jerusalem doing work for the British archaeologist James Starkey, and had time for some shopping. Her purchases give an idea of her sense of colour and style. For herself she “bought a frock of black Damascus silk embroidered in red & other gay colours & a cloak to match, also embroidered”. Damascus silk, or “damask”, is a reversible patterned silk fabric, usually in a single colour, where the pattern is formed by weaving using a satin weave technique giving it a lustrous, shiny quality. Myrtle wanted to get a dress for her mother too but they were all too large, so she had one specially made and told her mother that it was to be “in thick black Damascus silk & heavily embroidered. Most of the design will be in white but there will be a sprinkling of bright coloured flowers to please Father. It will be a frock you can wear for afternoons & would be suitable for an evening dress also, of course it has long sleeves & can be worn open or closed at the neck”. She proposed to post the dress to her mother in England direct from Jerusalem since if she had taken it with her to Cairo, where she would catch her ship home, heavy duties would have been payable to take the dress into Egypt first and then to England.

Standards were maintained at the dig house at Abydos even when there were no visitors. In December 1929 Myrtle told her mother: “we do try to make ourselves look nice for our evening meal. I always put on one of my pretty frocks (not my two evening ones of course)”. In December 1934 she wrote to her mother: “it is getting quite cold now. I put on my velvet dress one evening, it was very much admired & so comfortable”. The cold weather continued into the New Year, and in January Myrtle told her mother: “we all sit in the middle room with the big lamp & a little wood fire … I am so glad of my velvet dress … everyone envies me my forethought”. This dress was clearly a favourite. In December the following year Myrtle wrote to her mother saying that “the cold weather has set in, I am glad of my woollies when sitting in the temple & am wearing my red velvet dress in the evenings”.

As well as her own clothes, Myrtle also reported the clothes of some of the visitors to the Temple of Seti. In 1933 most of the Thomas Cook tourists were Americans, taking advantage of a favourable exchange rate. Myrtle was amused by some of their clothes, telling her mother: “there was a man yesterday with dirty white serge plus fours that bagged down to his ankles & a skin tight sweater in two shades of very bright blue. Some time ago I saw a lady Cookite in canary yellow trousers, I think she must have brought her ‘Lido’ outfit with her to liven up poor dull Egypt”. In February 1934 there were again many boat loads of Cook tourists, including “a couple that amused us very much. The lady wore a leather riding costume & the gentleman wore shorts & carried an ice axe. We have been torn with curiosity to know what the latter was for”. She and Amice considered “starting a book – of ‘Tourists I have seen’”, observing that “it would of course have to be illustrated to be worthwhile”.

Myrtle was always interested in local costumes and designs. When exploring Venice in November 1930 while waiting for their ship – the Aventino – to arrive, she and Amice left their luggage in the care of “a nice young man dressed up in a sort of Robin Hood hat & cloak in grey blue with plus fours”, whom she thought was “one of Mussolini’s soldiers”. One of her fellow passengers on board the Aventino that year was a Cretan lady, Mrs Calucci, who had “revived the ancient art of Cretan weaving & embroidering” and developed a local industry working with “the wonderful designs from the temple of Knossos, also some of the ancient peasant designs” where “the patterns are worked in, as the material is woven”. Mrs Calucci invited Myrtle and Amice to go to see the work when their boat stopped at Candia (now Heraklion) in Crete, and they “revelled in the most wonderful designs & patterns”. Myrtle bought her mother “a cushion cover with strange bulls & birds & lions woven in it” and a dressing gown for herself, while Amice bought bedspreads for her father, step-mother, and sister-in-law, as well as a dressing gown for her sister.

© Historical Museum of Crete

Myrtle found Crete “a lovely island” where “most of the people wore the old Greek peasant costume, knee boots, very full breeches, baggy white shirt & embroidered sleeveless waistcoat & a round cap”. Myrtle and Amice were not the only people who admired Cretan clothing. John Pendlebury, the young director of the Egypt Exploration Society’s dig at el-Amarna in the 1930s, who also worked at Knossos in Crete, wore a blue Cretan cloak decorated in black braid with scarlet lining, over a cricket jumper and shorts at el-Amarna.

In Jerusalem in 1935, Myrtle “noticed some black robed men with wide brimmed hats with long fur round the edge of the brim. They wore their hair cut very short except for two locks in front which hang in long corkscrew curls, one on each side of their faces”. She “learnt on enquiry that they are the Orthodox Jews”. She also observed the Arabs who wore “the picturesque flowing head-dress bound round with a coil of robe. Some of the women wear very gay embroidery”.

At the end of their final season Amice and Myrtle drove back across Europe, stopping in Athens. Having previously visited the Acropolis and the Archaeological Museum, this time they “went to another museum that had a collection of the old Greek national costumes & all the peasant embroideries which were very lovely”.

Photograph by Sharon Mollerus (2009)

Creative Commons 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Later in the same journey Myrtle described with delight the people they passed in Yugoslavia, wearing “the costume of their class & trade, they spin & weave in the old way. Nearly every woman has her distaff handy as she herds the cattle who graze on the plains & the dress is beautifully embroidered. The men wear shoes of hide with turned up toes & cross lacings”.

Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library, “National costumes of Yugoslavia” (1953)

The New York Public Library Digital Collections

Sources:

Letters: 24, 28, 29, 35A, 44, 54, 55A, 89, 92, 94, 140, 142, 144, 166, 179, 187, 216, 266, 271, 285, 289, 293, 307, 313, 341, 358, 381, 412, 413.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the University of Exeter Archives (GB 29 EUL MS 238) and the Levantine Heritage Foundation, for information about the Barkers in Alexandria

- the Palestine Exploration Fund, for information about James Starkey

- the Historical Museum of Crete, for the image of Cretan weaving and embroidery

- the Artefacts of Excavation project and Grundon, Imogen, The Rash Adventurer: A Life of John Pendlebury, London (2007), for information about John Pendlebury

- the Artefacts of Excavation project, for information about Percy Newberry and Amarna