‘The Way She Really Looked!’ – Winifred Brunton, Percy Newberry & Queen Tiye

Author: Campbell Price.

As part of a project to examine (re)imaginings of the Ancient Egyptian face at The University of Manchester, Campbell Price explores in this post some reflections within the letters of Egyptological artist Winifred Brunton in the Newberry Archive.

Among the extensive correspondence archives of English Egyptologist Percy Newbery (1869–1949), the Griffith Institute holds a number of letters from South African archaeologist and artist Winifred Brunton. These are an important source of information about Brunton’s own conception of her artistic practice, and the mechanics of its production and dissemination.

Image: Johannesburg Heritage Foundation / Wikipedia

Winifred Mabel Brunton (née Newberry – apparently no relation to Percy) was born on the 6th May 1880 – although sources are contradictory about exactly where, some citing London others recording the former Orange Free State in South Africa, where Winifred’s wealthy parents lived. She married Guy Brunton in 1906 and both studied Egyptology at University College London, where they were tutored by William Matthew Flinders Petrie and Margaret Murray.

Winifred participated in several archaeological excavations in Egypt alongside her husband and illustrated a number of the resulting publications. However, she is perhaps best known for two popular and influential books: Kings and Queens of Ancient Egypt (1926) and The Great Ones of Ancient Egypt (1929). These showcased Brunton’s colourful ‘portraits’ of historical individuals, reproduced from watercolour-on-ivory miniatures. Indeed, she was a member of the Royal Society of Miniaturists and it was specifically as ‘a talented miniaturist’ – rather than as an artist or an archaeologist – that Brunton was described in her obituary in The Times.

Some of Brunton’s paintings have been widely republished and were instrumental in forming a general impression of what Pharaonic royalty might actually have looked like. Brunton’s letters to Newberry offer fascinating insights into the genesis and production of the two volumes – and centre on one portrait in particular. Apparently among Brunton’s first subjects was Queen Tiye, the wife of Amenhotep III (c. 1390–1352 BCE), and it is with the purchase (or commission?) of this painting that the earliest correspondence with Newberry is concerned. On the 25th September (likely 1919), Brunton wrote to Newberry:

I am such an un-business-like person that I quite forgot yesterday that you would probably want to know how expensive Queen Tyi would be – If she is a success she would be the same price as the kings were – twenty-five guineas. If she is obstinate and refuses to behave nicely, I shall wash her off the ivory & feel disgusted with her myself. The piece will of course include the frame which I want to think over & design specially. Do you know anyone who works in gesso? I fear it will be 6 months or so before I get her done. I’m so keen on her I feel I’d like to start at once. Any details of costume, jewels or portrait photographs you can let me have will be most helpful.

By April 8th 1920, the painting was complete and Winifred (reluctantly, it seems) sent it in the post:

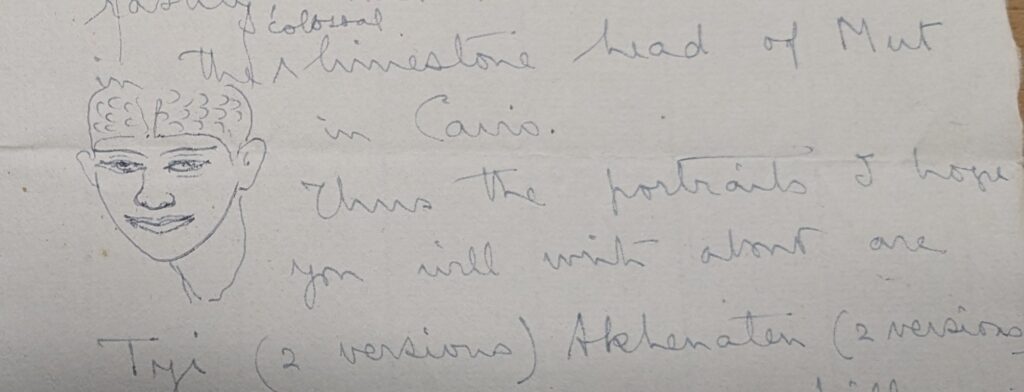

Dear Professor Newberry, Here is Tyi – I hope she will please you. The likeness is a compound of all the portraits I could get, but principally the little head Petrie got at Sinai. I found several profiles of her in Luxor Temple – the downturned mouth was quite unmistakable. The crown I took also from the Sinai head, except the colours which can hardly have been other than one sees on all the jewellery. In the colossal statue of Tyi and A. III in the central hall of the museum here she wears a headdress similar to the one in my picture. The necklace is done from her own electrum collar in the museum, which I take was for funerary purposes only. Anyway, I have put colours in, after a careful study of jewels of the period. The pectoral I copied from the one on her mother’s coffin – the only pectoral I could find of that period. One knows the reign was remarkable for its magnificence and the queen would be at the apex of all the splendour – hence the profusion of jewellery I have given her. I think a bronze or dull brass frame, flat and rather wide (about 2 and ½ to 3 inches) would suit her – not black as that takes the force out of the black wig. I have tried black frames and they don’t seem to do. If it isn’t too much trouble, I should like a wire to say she has arrived. I am so anxious all the time one of my pictures is in the post… I await your verdict with eagerness but I think you will like the lady – as I painted her I became quite convinced that that was the way she really looked!

Image: Global Egyptian Museum

The ‘little head Petrie got at Sinai’ is now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Doubtless Petrie’s own description of the fragmentary sculpture, published in his book Researches in Sinai in 1906, influenced Brunton: ‘Another queen has left here one of the most striking portraits ever carved by an Egyptian […] The haughty dignity of the face is blended with a fascinating directness and personal appeal. The delicacy of the surfaces round the eye and over the cheek shows the greatest care in handling. The curiously drawn-down lips, with their fulness and yet delicacy, their disdain without malice, are evidently modelled in all truth from the life.’

It is clear from other letters that Brunton was a regular exhibitor at the Arlington Galleries, on Old Bond Street in the West End of London, which specialised in miniatures. Several concern the loan of the Queen Tiye miniature, both for exhibition and to have it copied for eventual printing. Thus, for example, on May 21st 1924, Brunton wrote to Newberry:

I wonder if you got my letter from Cairo asking you to lend me the miniature of Tyi – and whether you have any objection to doing so? I am collecting my pictures for my show which starts on June 3rd. If you are kind enough to lend me Tyi, could you post her up to me? Or leave her at your club when you come up to town and I will fetch her there. I hope very much you and Mrs Newberry will come to my exhibition. I will of course send you cards for it in a day or two as soon as I have them. I have seen Captain Bruce Ingram & he is very kind and helpful and is going to put some pictures in The Sketch or The Illustrated.

Brunton’s work on Egyptian and other ancient peoples was featured throughout the 1920s in the Illustrated London News and an associated Society magazine, The Sketch. Mention of Captain (later Sir) Bruce Ingram, who was editor of the ILN from 1900 until his death in 1963, gives some indication of the personal networks at work behind the scenes. Ingram was a professed Egyptophile and a close friend of Howard Carter, and so perhaps it is no surprise that he took an interest in, and thus facilitated the dissemination of, Brunton’s work in the press. The ILN notices and write-ups for her London exhibitions no doubt increased their popularity.

Likely as a result of interest shown in her works at these shows, Brunton entered negotiations Hodder and Stoughton about a book publication and approached Newberry among other eminent Egyptologists to contribute essays of ‘an average of 3500 words per portrait’ to a proposed volume of ‘Kings and Queens’. She asked him specifically to write on the subject of the Amarna royal family, a period of intense interest at the time. In a letter dated only ‘Monday 13th’– which must have been written between 1923 and 1925 – Brunton was excited by the prospect of Carter’s finds in KV62, and of the king’s unwrapped body as a potential subject:

I am indeed delighted that you will write up those Tell el Amarna people for me. But I want Akhenaten too! And if Tut’s mummy is undone in time I may paint a portrait of him too next winter! So perhaps it would be as well to treat the family as a whole. Let us hope for some valuable information from the tomb next winter.

In the eventual 1926 volume, Newberry did not in fact ‘write up’ the Amarna kings, instead this section was authored by Thomas Eric Peet. Newberry did however contribute a chapter on ‘Menes: the Founder of the Egyptian Monarchy’ to the 1929 follow-up The Great Ones of Ancient Egypt. Brunton wrote effusively to Newberry on the 15th of August (of 1928?): You have given me a beautiful article, which will enormously enhance the value of the book. Indeed I feel now that the only credit I can claim is inducing you and the other scholars to write such valuable studies. It is possible that the “lay” mind may find your writing of this article “stodgy” as you say, but I don’t think so. In any case, I was disappointed in the first book that it was too magaziney(?) – & except for Peet’s work hardly appealed to students. But they will want this new book if only for your chapter. Mr Glanville has given me a very good article on the Amarna people but he freely acknowledges that he owes much of it to your researches.

Several of the Egyptologist contributors to Brunton’s volumes emphasise her close attention to ‘the evidence’ – both from two- and three-dimensional sculpture and the mummified moral remains believed to belong to the individuals themselves. The assumptions involved in such statements, and the way her ‘portraits’ were framed then and have been received since, is repaying closer study. The light shed by her letters to Newberry is vital for understanding the paintings’ importance in informing popular ideas of the ancient Egyptian face.

Acknowledgements:

I am grateful to Creative Manchester at The University of Manchester for supporting a part-time secondment from my duties as Curator of Egypt and Sudan at Manchester Museum to enable my research. Thanks are due to Dr Daniela Rosenow and Jennifer Turner for facilitating my visit to consult the Brunton correspondence in October 2024.