Shoes and clothes – 1

Author: Susan Biddle.

This post is the first of a series looking at clothing, and focuses on the day-to-day clothes worn by Myrtle Broome and Amice Calverley.

As befitted an artist with an interest in the Arts and Crafts movement, Myrtle was interested in clothes, both her own and others. She kept her parents, particularly her mother, informed about what she and others were wearing.

Myrtle needed clothes for a wide variety of situations, including work in the Temple of Seti, relaxing at the dig-house, socialising with friends, and trekking into the desert and to the coast. The weather was likely to be hot at the start of the season, and could be very hot by the end particularly if they continued work into May; in between, it was sometimes very cold. Myrtle told Miss Jonas, the secretary of the Egypt Exploration Society: “I have a positive dread of luggage bothers & always travel with as little of my own as I possibly can”. She did not always use her full personal baggage allowance, and her wardrobe for any particular situation must have been quite limited. She probably found it difficult to anticipate just what would be required when packing for her first season, but soon after arrival at Baliana in October 1929 she reassured her mother that “my clothes seem very suitable & comfortable”.

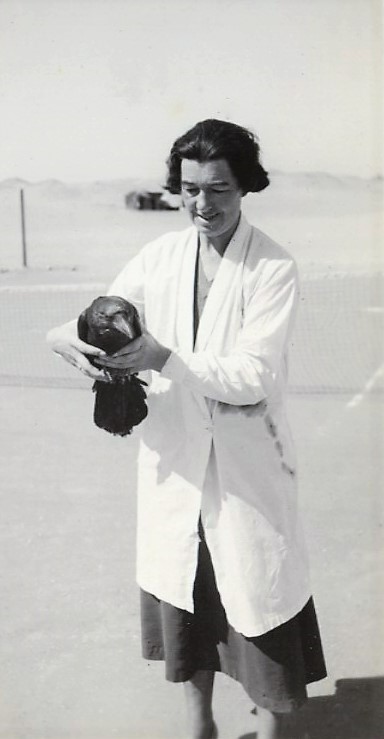

For work in the temple she and Amice dressed practically in overalls. At the start of the 1933 season Myrtle indicated to her mother that “the new overalls are very comfortable”.

© Amice Calverley (?) (1933)

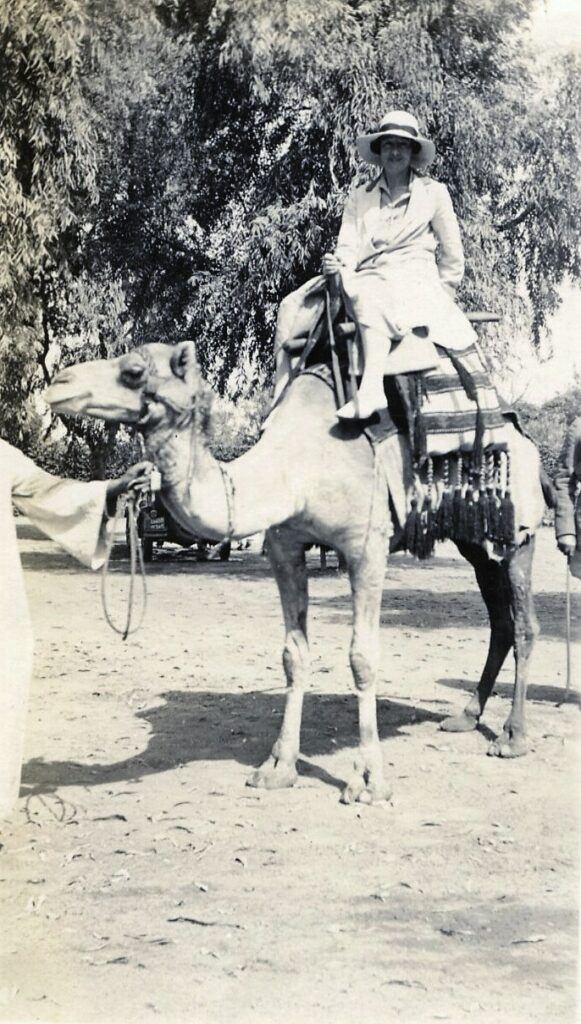

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

She appreciated the importance of wearing a hat. In February 1932 she told her mother that another member of the team, Linda Holey, was “on the sick list now, it is a touch of sunstroke. She will not wear a hat here, in spite of warnings from all of us, her chief ambition is to get a sunburnt complexion”. Myrtle’s cabin luggage included a hat box, but even with this protection in October 1934 she needed to use the electric iron on board the SS Tuscania to “iron the brim of my shady hat which had got a little dented in the hat box”.

© Amice Calverley (?) (date not known)

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

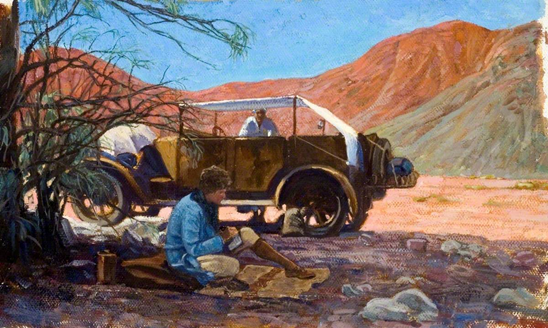

Myrtle refers far more often to skirts and frocks, than to trousers. Even when trekking in the desert or riding camels, it seems she often wore a frock or skirt. In April 1934 she spent part of her holiday on a three-day trek into the Eastern Desert and explained her camping arrangements to her mother: “I removed my shoes & stockings, pulled off my frock & put my nightie over my underclothes – which were of the scantiest possible – then I slipped my feet into one pocket of the saddle bag, pulled the rug over me, & the mosquito net down, & I was as cosy as anything”. In the morning, she again put on a frock. However she and Amice did also wear trousers. In January 1931 she told her mother: “I am wearing my new corduroy breeks now, they are splendid & much admired”. When she painted Amice on one of their desert trips, Myrtle showed her in trousers and boots.

At night Myrtle wore a nightdress rather than pyjamas. For Christmas in 1929, Amice gave Myrtle “the daintiest pale pink cambric nightie, handmade & embroidered in Italy”. She also wore a hair net at night; in January 1933 she asked her mother to get her, from the hairdresser in Watford, “two sleeping caps, pink or yellow. I like the plain net sort, they are called Lady Jayne I think & cost about 1/- or 1/6 each. The ones I have show signs of wearing & I do not think they will last the season”. Each of the four caps was sent enclosed with a separate letter, to avoid the delays and duties to which parcel post was subject, and the four together formed her birthday present. Three of the caps her parents sent her were plain, but the fourth was a “fancy one” which Myrtle told them she would keep “for swell occasions”.

A dressing gown was important both to preserve the proprieties when trekking in the desert and to maintain status when travelling at the start and end of each season. In Cairo, at the end of her first season, Myrtle delightedly reported that she had bought “a gorgeous pink & lemon dressing gown for myself. I need the latter badly, my cotton one looks rather a wreck since its journey to Kharga & is not at all suitable to a First class passenger – dressing gowns are such public garments on board ship. This one is just a very rich piece of artificial silk made up quite square like this [sketch]. It drapes beautifully & there is lots to wrap round one’s legs”.

When stopping in Crete in November 1930 en route to Egypt, Myrtle seems to have acquired another dressing gown which came in useful later. In April 1934 she spent part of a short holiday trekking in the Eastern Desert. After a night camping in the desert near the village where her former Arabic teacher lived, she was just drying herself after her morning wash when her teacher and his uncle arrived. She told her mother that “there was nothing else I could do but receive them in my nightie & dressing gown!! But fortunately I had on one of my nice long pink silk nighties & my Cretan dressing gown, so probably my visitors thought I was wearing my robes of state in their honour”.

Many of her letters include references to stockings. In the course of the first season her mother sent Myrtle four silk stockings, each leg again sent separately under cover of a letter so as to avoid the problems of parcel post. Stockings required suspenders, and in November 1931 Myrtle had to write to her mother asking for “a yard of suspender elastic” as “the suspenders on an ancient pair of corsets I left out here are rather tired, but if renewed will be quite useful”. As usual she wanted the elastic cut into four pieces, so her mother could send each piece separately. A month later Myrtle reported that all four pieces of elastic had arrived and that “my stockings are keeping up as they should”.

The winter could be cold and windy, and at times Mrytle and Amice struggled to keep warm when working in the Temple of Seti. In December 1935 Myrtle told her parents that Amice “wraps the scarf round her middle, crosses it behind her back & pins the ends across her chest & this keeps out the coldest winds”. This scarf was one which Myrtle and her mother had given Amice. The previous April, Myrtle had indicated to her mother that “Amice would love to have a long blue woolly scarf, so when I return I will get the wool & perhaps you will knit it, so it will be a joint present from us both” for Amice’s birthday.

© Myrtle Broome (date not known)

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Myrtle draped herself in a scarf which was made for her with wool spun by their head servant, Sardic, and woven by a local weaver, Ibrahim, with a fringe twisted by Ahmed, another of their servants. Sardic was a Bedouin whose “tribe has worked with wool for many generations, he spins as naturally as a fish swims”. Back in January 1930 he had wanted to make Myrtle “a shawl in coloured wool according to his own ideas”, and Myrtle provided him with red, green, yellow, and white English wool for the project. The resulting shawl was “such a pretty thing”; she was struck that, although the Egyptians had used English wool, “they have used the colours in such a way that they look utterly different to any of Miss Collins’ [an English friend with a weaving practice] colour schemes, it is truly Eastern & so simple that it seems perfectly obvious”. When in January 1931 Myrtle first wore the scarf to work in the Temple of Seti, which was very cold, the men were delighted. She told her mother that “it made a nice warm wrap & I was glad of it on my draughty perch near the roof”.

None of their old clothes was wasted. Old stockings came in useful when Amice and Myrtle were administering first aid to the local people, Myrtle telling her mother how they “put a bit of old stocking over the bandage & tie it round the leg” to keep bandages in place on the locals to whom they provided medical treatment and had “used up lots of old legs of stockings this way. They do splendidly”. Other clothes were passed on to local villagers.

Some old clothes came to a more spectacular end. At the end of their final season, Amice and Myrtle drove across the Eastern Desert and up the Red Sea coast to Suez, the first section of their long drive back across Europe. They stopped at Hurghada, where they made a brief visit to the Roman ruins at Mons Claudianus with Hanafey Bey, an inspector of mines who had become a friend. Myrtle explains that “we were of course wearing our oldest clothes & … had rather a joke with Hanafey as to whose shirt was in the worst condition”. The frontier police permitted Amice and Myrtle to continue north along the lonely coast road without escort because Hanafey was to follow them a day and a half later for his own purposes. A government lorry was also following two days behind Hanafey, so if they broke down or otherwise got into trouble, help would be available. One morning as they drove up the coast road, “Amice decided the shirt she was wearing was no longer decent, so a few miles along the coast we found some flotsam & jetsam which we gathered & made a glorious scarecrow which we set up by the side of the track with one arm pointing the way we had gone & in the other a message written in my best Arabic to convey our greetings to Hanafey when he passed that way”. When Hanafey caught up with them at their next overnight stop, he had been greatly amused by this, immediately asking them why they had not dated their message.

© Myrtle Broome (1937)

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Sources:

Letters: 33, 44, 49, 54, 55A, 55B, 56, 88, 97, 102, 110, 111, 131, 140, 144, 154B, 169, 204, 218, 219, 238, 285, 292, 334, 363, 409.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Egypt Exploration Society, for access to their Abydos archives

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for Myrtle Broome’s photographs and painting

- the Victoria & Albert Museum, for the link to the Arts and Crafts movement