Shoes and clothes – 3

Author: Susan Biddle.

This post is the third in a series looking at clothing. This instalment focuses on the clothes worn by the servants who worked with Myrtle Broome and Amice Calverley, and by some of the other Egyptians Myrtle knew.

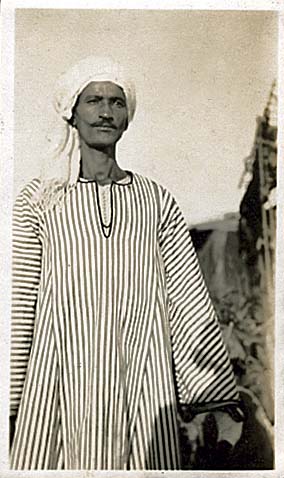

The Egyptian servants all wore galabiyas, which Myrtle described to her mother on various occasions. In December 1929 Sardic, the head servant, returned after a few days’ sick leave “in a glorious daffodil yellow satin gallibea with maroon stripes”, which Myrtle and Amice thought “must be to celebrate his recovery”. Galabiyas were regularly replaced. At the end of Ramadan in 1930 all the servants sported new galabiyas, as did Mohamed, a local man whom Amice and Myrtle were treating for an infected hand and who appeared in “a new galabia of blue & white stripes”. When they had re-bandaged his hand, Myrtle took a photograph of him. She told her mother that Mohammed “was delighted to be photographed but oh dear the effect on him was awful. One can put boiling hot dressings on him, & cut big lumps of bleedy flesh & stray bits of tendon off, & he just smiles sweetly & says it doesn’t hurt, but just show him a camera & he becomes as stiff as a ram rod, tightens his facial muscles up to such a degree that it is difficult to believe he is the same beautiful graceful creature”.

Photograph by Myrtle Broome (1930)

Bushey Museum & Art Gallery

For Christmas 1931 Amice and Myrtle gave Sardic a new black cloth galabiya, which he fetched himself from the local tailor in the nearby village of Baliana. The following December Myrtle told her mother that Abdullah, the youngest servant, was “getting very tall. He has grown out of last year’s galabiyas & we are having new ones [made] for him”. Abdullah kept growing – in January 1936 Myrtle reported that “Abdullah has a new galabia & he goes about crackling & rustling like a bag of sweets at a theatre. He looks simply enormous in it, he is the tallest of our servants now & has a moustache”. In December 1936 Amice and Myrtle bought each of the men a new galabiya for the Christmas festival; Myrtle told her mother that each of these was to be made with “blue & white striped cotton, the stripes vary in width & design, but the general effect is the same”.

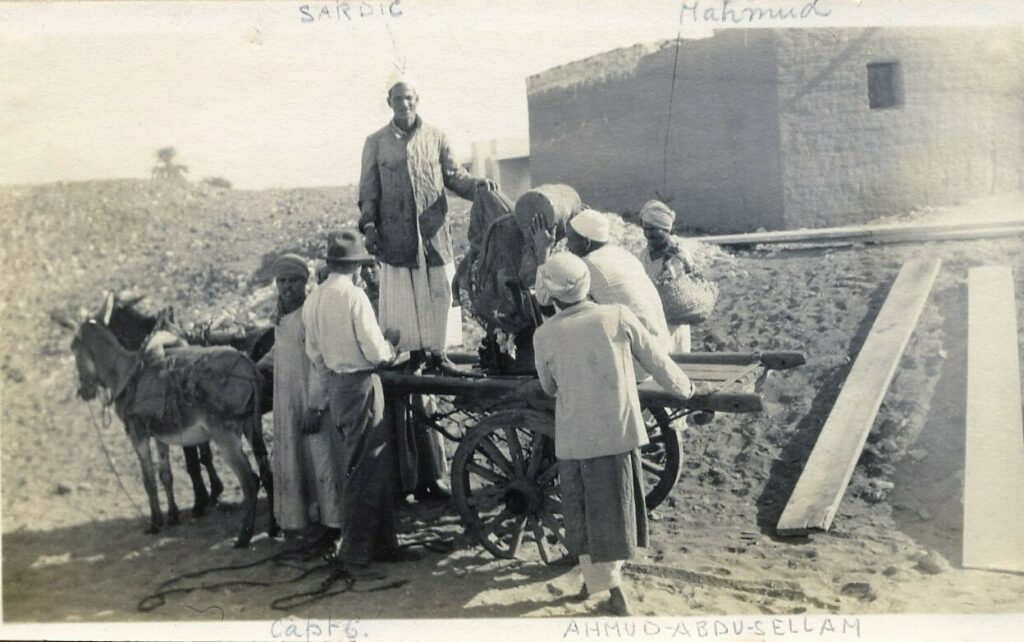

Photograph by Myrtle Broome (1930)

Bushey Museum & Art Gallery

Under their galabiyas the men wore a garment which Myrtle described as “a long sort of vest”. At Sardic’s request, in January 1930 she provided him with 4 pounds of fine white wool, sent from England washed and ready for carding, as he wanted to make such a garment with English wool. Unfortunately the English wool “proved most disappointing. It is no good at all out here, it dried up during the summer & split into tiny lengths when they tried to spin it. […] Isn’t it a pity – Sardic is very sad about it”. However, although he “could not spin it as fine as he wished to because the heat had made it so brittle”, in fact she later found that Sardic “was able to use most of it”.

At the start of the second season Myrtle brought the servants presents of scarves from Barkers, a department store in Kensington, London. The following February she told her mother that one of the servants, Ahmud Ibrahim, was wearing his scarf and “looked simply splendid in it. He had wound it round his head with one end with the heavy black fringe that I’d made hanging over one shoulder, his robe was of a very deep blue cloth. The effect with his brown skin & fine features was very beautiful”.

The school masters who taught Myrtle Arabic from the third season onwards were impressively dressed. After her second lesson Myrtle explained to her mother that Sheikh Sarbit, “evidently considers it a great honour to come to teach us, & I think he puts on all his ceremonial robes one over the other in order to be equal to the occasion – he fair rustles”. In April 1934 Myrtle was invited by Sheikh Sarbit to visit him at his home. Since his wardrobe was in the receiving room, she had the opportunity to describe his dress in some detail as he changed from outdoor to indoor clothing. She reported back home: “he first removed his outer guftan of a light weight blue cloth. Under this he had a galabia of shantung coloured native silk, then off came his shoes & socks & a small boy brought him his heelless slippers”; then, after disappearing for a wash, Sheikh Sarbit “reappeared & put on a clean cotton guftan over his silk under robe”.

Men’s clothes were significant in Egypt. When Amice asked Sardic to write a letter in Arabic for her to a Cairo rug merchant, she and Myrtle were surprised when he “asked to have the man’s clothes described to him so as to know how to address him in the letter. It seems if he wears European clothes he has to be called ‘Effendi’ but if he wears a galabia the correct form of address is ‘Sheikh’”. The local inspector of antiquities was one of those who wore European clothes. When he came for lunch in November 1936 Myrtle explained that “he had on the most amazing patterned suit we have ever seen. There were blue stripes fading to pale blue & then dark grey stripes fading to pale grey, a sort of shadow effect. We had all we could do not to fix too rapt a gaze upon it”. The inspector was not the only one whose choice of suit attracted Myrtle’s critical comment. In April 1936 she had dinner with a former member of the team, Otto Daum, who was “suffering an attack of jaundice. I have never seen anyone so yellow, & as he wears a greenish grey suit the effect is awful”.

The Syrian housekeeper, Mrs Nellie Maouchy, who was known as “Nannie”, was no fashion plate. For Christmas 1929 Myrtle had made her “a magnificent pair of garters out of some shoulder strap ribbon … all puckered on elastic, this was a huge joke as her stockings are always coming down”. In January 1930 at Nannie’s request Myrtle asked her mother to send from England for Nannie “half a dozen small cap shape hair nets, black or very dark brown”, preferably silk “as they don’t tear as easily as the real hair”. These “would be useful for wear in the morning when she is making beds etc”.

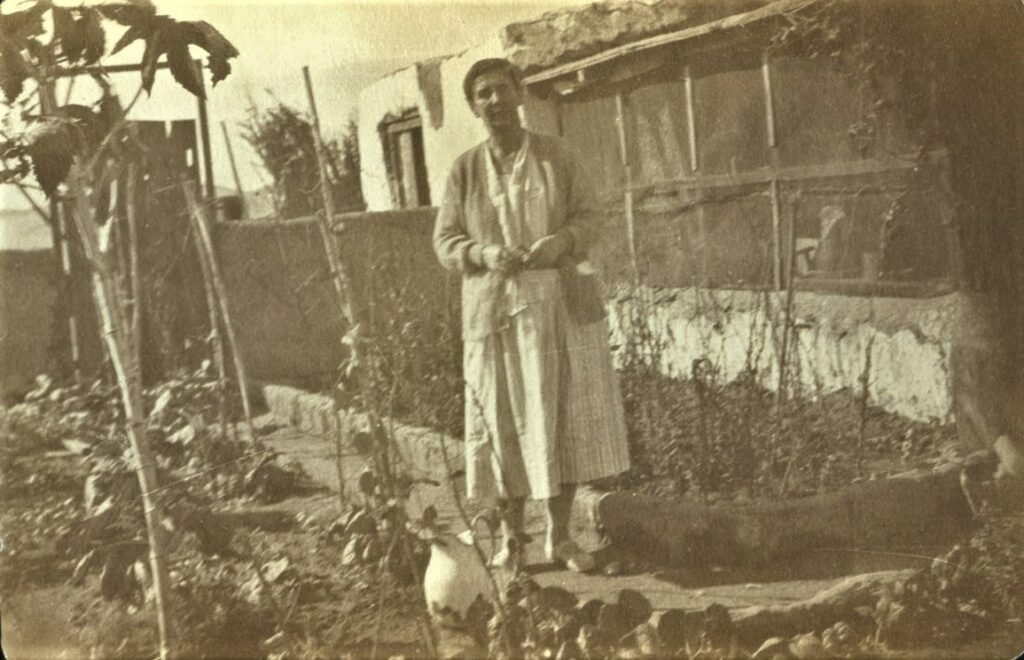

Photograph by Myrtle Broome (probably 1929)

Bushey Museum & Art Gallery

Myrtle took Nannie a new skirt as a present at the start of the third season. She told her mother “Nannie was very pleased with her skirt & it fits her very nicely. […] The skirt length is perfect.”. Amice’s present to Nannie on the same occasion was “two pairs of combinations, Nannie said they were just what she wanted & the only fault she could find was, that when they were worn out she would have got so used to them & would be too poor to replace them & then it would be worse than if she had never had them” – clearly Nannie could be hard to please.

Myrtle also described the dress of some of the Egyptian women whom she met. In March 1931 she and Amice visited the new daughter-in-law of one of their servants, Ahmud. Myrtle told her mother that “the little bride was dressed in an orange silk dress with a simple band round her head & a gay coloured veil hanging down her back. She wore many anklets & bracelets & a fine gold necklace the gift of the bridegroom”. The following year Myrtle and Amice attended the reception lunch on the day following the wedding of the son of another servant, Ahmud Ibrahim. Myrtle reported that this bride “was very resplendent in pink silk & a many coloured veil & barbaric gold & silver ornaments”, while the bridegroom “wore a striped blue & white & beige satin gallabea with a blue cloth robe over it”. In February 1934 Myrtle visited Sheikh Sarbit at home in his village where she met his young wife, who was “dressed in blue flowered silk with a head veil of embroidered silk in a pale shade of blue. […] She had gold coins to weight her long plaits of hair & a fine gold necklace made of coins & gold bracelets & heavy silver anklets”. The interest in dress was reciprocated, Myrtle telling her mother that Sheikh Sarbit’s wife similarly “took a great interest in all I was wearing”.

In January 1930 two Egyptian princesses, cousins of King Fuad, came to see the Temple of Seti at Abydos. In answer to her mother’s question, Myrtle explained that the princesses “did not wear veils. They belong to the New Egyptian party & try to be ultra European”. In contrast, when the local doctor’s wife and her sisters visited in February 1934, the women wore veils, which had to be washed out after two of the ladies arrived with bloody noses when their driver went too fast over the rough ground to the camp. When King Farouk visited in January 1937, the Queen Mother, Nazli Sabri, “wore fashionable French clothes & no veil, some of her ladies-in-waiting wore a tiny yashmak over the lower half of their faces”.

Amice suggested to the king’s master of ceremonies that some travelling musicians who frequently entertained the Abydos team should play for the royal party in 1937. Their playing was well-received, and King Farouk “was so delighted that he gave them £5”. A few weeks later the musicians came to thank Amice and Myrtle for arranging for them to perform during the King’s visit, and Myrtle noted that “they were all dressed in new galabias, they had evidently been spending the King’s bounty”.

Myrtle was distressed to see that many of the local Egyptians were in contrast “so poor that the children are dressed in any old rag that will hang together”, and tried to help. In April 1931 she gave the wife of one of their servants “the old frock I brought with me to wear in the evenings here, it was a sort of fawn with roses & pink crepe-de-chine let in to the skirt […] to make into a frock for her little girl”, whom Amice and Myrtle had treated for ophthalmia. The little girl came to show Myrtle the resulting dress and was “as proud as punch”. Myrtle had “also turned over my green gingham dress for one of the others”. In December of the same year she asked her mother: “do you remember the old pinkish jumper of yours I had last year? I have now given it to one of the boys who does odd jobs. It is very cold at sunset & early morning & he was shivering in a single cotton gallibea. He is an orphan so has no one to pass on cast off garments. He was so delighted & proud & it fits him beautifully”. She also made small garments for some of the local children and told her mother these had “been very gratefully received, & if wishes are granted I am in for a very long life!”.

Sources:

Letters: 48, 49, 55A, 55B, 57, 69, 96, 97, 111, 114, 124, 133, 153, 158, 200, 213, 268, 270, 283, 364, 379, 383, 387, 393, 396.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for Myrtle Broome’s photographs