A busy five days in Cairo, 10–14 October 1929

Author: Susan Biddle.

In this post, join Myrtle Broome in Cairo, visiting the British Consulate, the Gezira Sporting Club, the Cairo Museum and the Pyramids, and meeting some “Egyptology celebrities”

Myrtle Broome, together with Amice and Hugh Calverley, arrived in Cairo by train late in the evening of Wednesday 9 October 1929. They spent the next five days in a whirlwind mix of socialising and practical preparations for the coming months.

Amice and Myrtle spent the first night at the “Cecil House” hotel, apparently an economical choice and not the equivalent of the more up-market Cecil Hotel in Alexandria. They had a disturbed night when workmen arrived at dawn to work on the house opposite, and decided to relocate. If this was the “Cecil Pension” in Rue Tashtomar, they may have been lucky not to be disturbed all night – during the First World War complaints were filed about a brothel opposite the Cecil Pension which held raucous parties into the early hours. They spent the next four days at the Gresham Hotel, despite the increased cost (16/ a day). The other European member of the team, C. M. Beazley, was already staying there and recommended it as “nice and peaceful”.

During their first morning in Cairo, Myrtle registered with the Consulate so they would know where to find her in case of any disturbances, such as the riots which had occurred in Palestine in August 1929. She and Amice would leave their passports with the British Consul for safe-keeping while they were in Abydos. They also got the permits required for the season’s work from the Service des Antiquités, and went to the Cairo Museum. There they met Reginald Engelbach, then the Assistant Keeper of the museum, and Battiscombe Gunn, then the Assistant Curator. For reasons which never become clear, Reginald (or Rex) Engelbach was known to Myrtle and her parents as “the Imp” – perhaps a joke, promoting him from Rex/King to Imp(erator)/Emperor.

Myrtle spent her afternoon in the more frivolous activity of shopping for new silk stockings of a better colour to go with her crepe-de-chine frock for tea at the Sporting Club, which she described as “the smartest gathering place in Cairo”. Established in 1882, with membership originally restricted to the British Army and British civil servants, by the 1920s members of the Gezira Sporting Club also included wealthier Egyptians as well as other foreign residents. On the island of Zamalek, the club’s grounds had previously been part of the gardens of the Gezira Palace, built to house international dignitaries visiting for the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.

Photograph by Jorge Lascar, Licence

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gezira_Sporting_Club_(14609292100).jpg

The club’s grounds still included flowers and trees, as well as a tea pavilion, an 18-hole golf course (the first in Egypt), tennis courts (from 1907 it was the home of Egyptian lawn tennis), croquet lawns, and facilities for polo, cricket, squash and horse-riding. Along with the Turf Club, it was a social hub of the ex-patriate community in Cairo. It was nationalised in 1952, but continues to operate as a sporting club for members today.

The following morning Myrtle opened an account with Barclays Bank so that she could cash cheques by post from Baliana. The Thomas Cook bank could only cash cheques in person, so her account there was of “no earthly use to [her] up country”. She and Amice returned to the Gezira Sporting Club for tea and in the evening joined a party of friends watching a thrilling pelota game, “the most skilled ball game [she had] ever seen”.

Unfortunately, when enjoying tea at the Gezira Sporting Club, Myrtle was “eaten all over the exposed parts of [her] legs and feet by the grandfather of mosquitoes” and, by the time they returned to their hotel at 1.30 a.m., her feet were very swollen. She eased the burning by wrapping them in rags soaked in weak carbolic solution and applying Homocea cream – this seems to have been a contemporary cure-all for ailments ranging from haemorrhoids to neuralgia via rheumatism, eczema and flesh wounds. Despite all this, she had to miss the planned trip around the Cairo Museum with Rex Engelbach on Sunday morning, as she could not get even her canvas shoes on her feet. This was a great shame because, as creator of the Cairo Museum Register, Rex would have been the ideal guide.

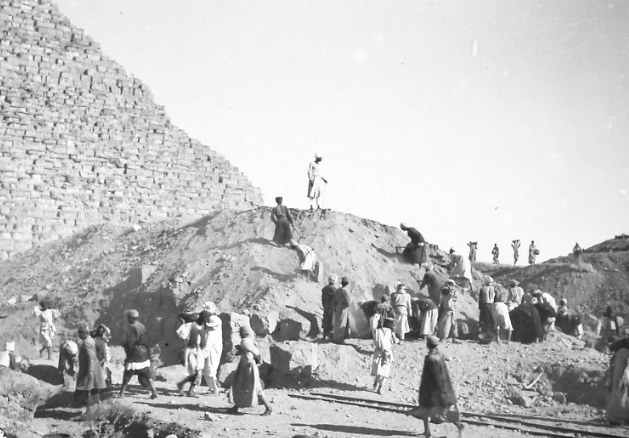

Fortunately she was able to join the trip to Dr Junker’s camp at the Giza pyramids in the afternoon. While the others walked, Myrtle travelled in state on a donkey and had to content herself with viewing things with field glasses, while the others went round Dr Junker’s excavations. Dr Junker had spent his last seven seasons (1912–1914 and 1925–1929) excavating the cemeteries around the Great Pyramid, and was about to start work at Merimda in the Western Delta. This party of visitors were presumably looking at his excavations during the previous (1928–1929) season, when he worked on the cemetery to the south of the Great Pyramid (GI-South). Myrtle’s swollen legs did not prevent her doing full justice to the iced cakes he had provided for their tea.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (KHM_o_neg_nr_0517); Digital Giza

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (KHM_AEOS_II_2866); Digital Giza

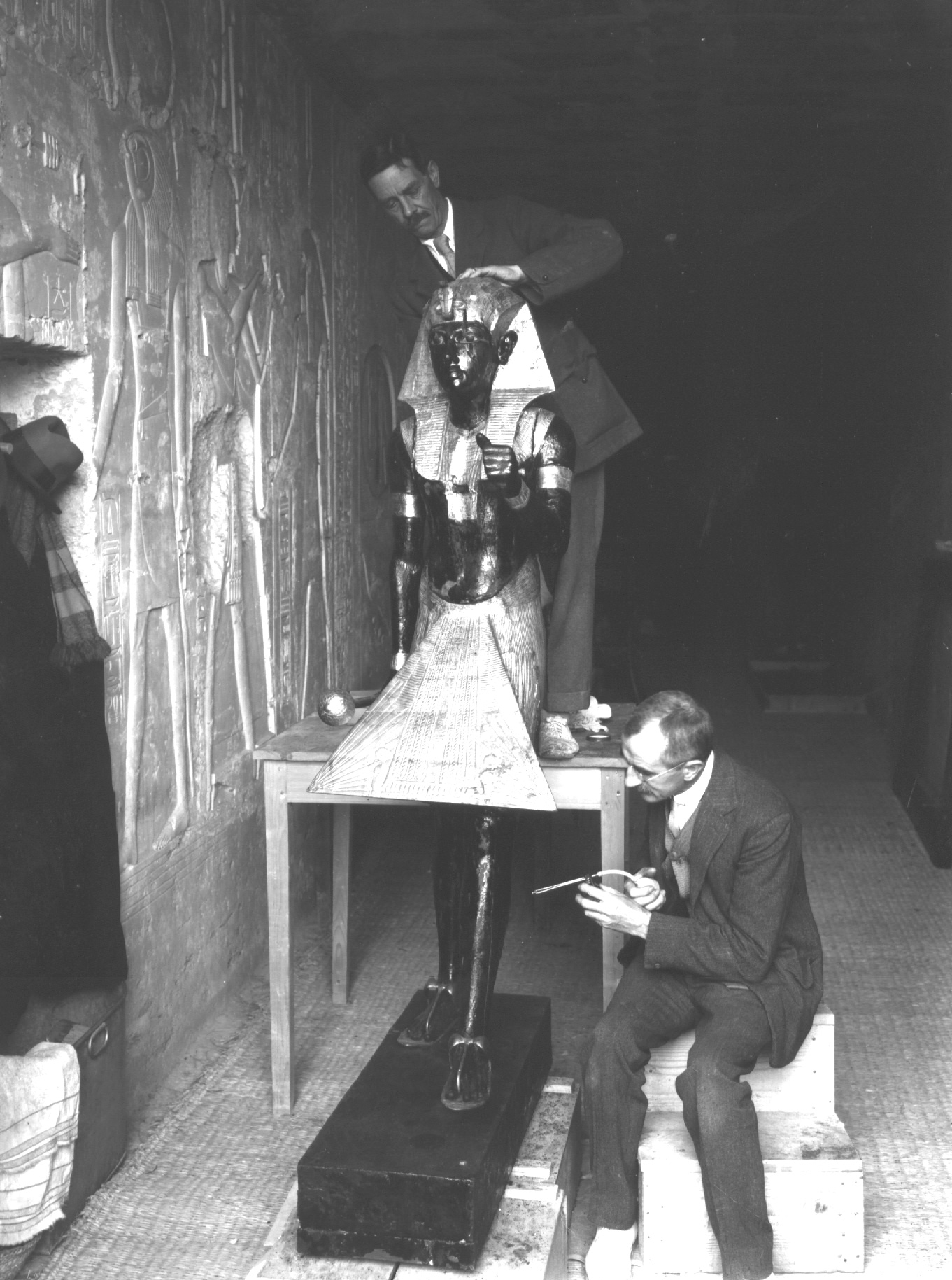

At Gresham House Myrtle also met Alfred Lucas, “a famous analytical chemist [who] was employed in the treating and preserving of all Tut’s things”. Myrtle was impressed that Lucas had “also worked a lot for C.I.D. and [had] helped detect a number of criminals”. A pioneer of forensic science and author of the first text book on the subject, “Forensic Science” (1921), Lucas was also an expert in handwriting analysis and firearms evidence, and was nicknamed “Egypt’s Sherlock Holmes” by the Egyptian Gazette, the main English language newspaper in Egypt in the 1930s.

Later in the season Lucas visited Abydos for five days to advise Amice and Myrtle on how best to clean some of the painted surfaces of the temple walls. Three years later he showed Myrtle and Amice “all the latest Tut things that he has been restoring in the Museum” and Myrtle told her mother “the gold shrines are marveloussic. We were able to go inside them & examine them closely, we also saw the model boats, jewel cases[,] furniture, chariots etc.” Not surprisingly, “the various parties of tourists who were going round on their own, or with dragomanssic, were green with envy”.

Photographer Harry Burton

© Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

On their final day in Cairo in October 1929 an RAF officer advised them on what to look for when considering whether there was a suitable place for a landing strip near Abydos. This would give the team a third line of retreat, if anything should prevent use of the railway and the Nile. Myrtle “almost hope[d] something would happen – it would be so thrilling to be rescued by aeroplanes”, but immediately reassured her parents that “of course nothing like that is in the least likely to happen”. Two years later, the RAF “lent” the Abydos team Leading Aircraftman Clark to fix their generator. Once this was done, they drove into the desert to look for a suitable landing ground and he again showed them what was required and how to mark out a site if they found one. However it seems no suitable site was ever found, and Myrtle had to wait until 1934 for her first flight, from Heliopolis to Alexandria.

Sources: letters 29, 30, 31, 35A, 43, 44, 149, 194, 290.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, for the opportunity to work on Myrtle’s letters and their ongoing support for this blog

- the Artefacts of Excavation project, for biographical details for Reginald Engelbach, Battiscombe Gunn and Alfred Lucas

- the Digital Giza project, for information about Hermann Junker’s work at Giza

- Mark Gilberg, for information about Alfred Lucas in his article (1997), “Alfred Lucas: Egypt’s Sherlock Holmes”, Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 36 (1), p. 31–48 (DOI: 10.1179/019713697806113620).