Animals – 5: Animal dangers

Author: Susan Biddle.

Myrtle Broome’s love of animals shines through many of her letters, but she was also well aware of the dangers which animals could pose. This post is one of a series looking at the animals she encountered, and focuses on some of the risks she met and how they were addressed.

Whilst working at the Temple of Seti I at Abydos in the 1930s, Amice Calverley and Myrtle Broome treated a number of the local villagers for dog bites. In January 1930 Myrtle wrote to her mother that “I had a woman with a bitten arm to attend to yesterday. A savage dog had seized her just below the elbow. Fortunately she had the sense to come here at once. Nannie [the Syrian housekeeper] heated some water & we bathed it well with hot Lysol [a disinfectant] & I painted all the tooth marks with iodine & bandaged it up”. In April the same year she told her mother: “we now have a wee girl to attend to each day, a dog has bitten her cheek, such a nasty gash by the ear. She is so brave about it, we give her a sweet after the dressing because she is so good”.

But dog bites could present much more serious risks. If someone is bitten by a rabid dog, the risk of contracting rabies is typically about 15%, but can be up to 60% depending on factors such as the number, depth, and location of the bites, as well as the stage of the illness in the infected dog. Once symptoms appear, there is no known cure. However, by the 1930s, post-bite vaccination treatment was available.

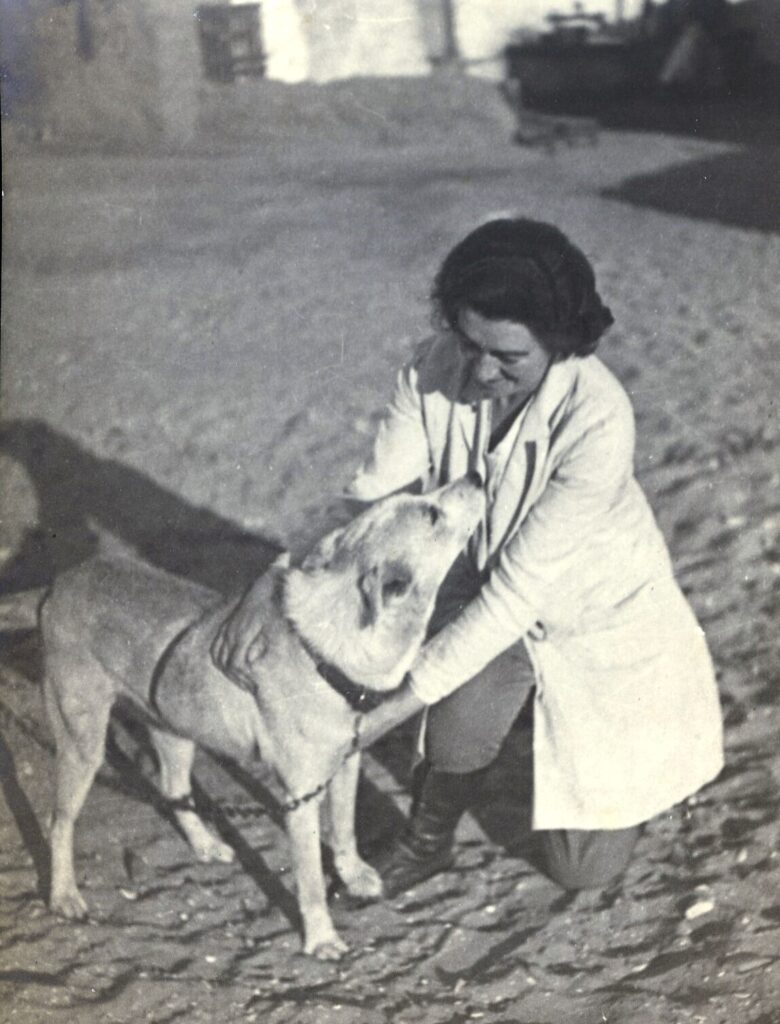

Myrtle had her first encounter with a mad dog just six weeks after arriving in Egypt for her first season working in Abydos. On 22 November 1929, when she and Amice returned on their donkeys to the dig house for lunch, they heard their dog Wip-wat barking violently, and “when we came in sight of the house we saw a wolf like creature running round in a strange sort of way. It didn’t seem like a dog & yet the colour was too light for a wolf”. Fortunately they were accompanied by Sardic, the head servant, and two of the other servants, all of whom “were off like a shot, galabiyas tucked up all shouting at once. The animal made off, still running in circles or to & fro. They all got out of sight over the next sand hills, then we heard two bangs. We left our donks at the house & scrambled after the hunt. We found Sardic had shot the creature. It proved to be a mad dog. It was very gaunt, & its mouth was all dribbling & foaming”. Sardic had killed the dog with “a beautifully clean shot through the head, & a very lucky thing too, these half wild dogs often do go rabid & cause a lot of trouble (another reason for carrying a gun”.

When they returned to the dig house they “looked our dog over well to make sure he had not been bitten but he was all right”. Two days later there was an unexpected sequel to this incident. Myrtle told her father that “because the mad dog had been round our dwelling & because one of us caused its soul to be torn from its body all who saw it are in danger of being entered in by the evil spirit (in such a case our servants are one of us, we provide them with the means of living therefore they are like blood relations). In order to avert this dreadful thing the priest is coming tomorrow to read prayers over us, & we are all to eat bread that he has blessed, even our own dog will be included in this ceremony, also the donkeys we were riding”.

Myrtle described the ceremony in detail to her father and asked him to keep the letter handy for future reference, as she and Amice intended “to write it up carefully because as far as we know such a thing has never been published in any works on Modern Egyptian magic”. The priest brought seven loaves of bread (like pancakes), seven dates, and a tiny cup of oil which he placed on a stool, with a water jar alongside. When everyone concerned – including Wip-wat – was gathered in a circle round him, the priest read a prayer and then struck each of them lightly on the head with a stick saying “Depart oh fear”. Three small boys who had come with the priest then walked round the group seven times one way, then seven times the other way, chanting. Each boy asked the priest for deliverance from evil and was given some of the bread consecrated with the oil, and then the dates similarly consecrated; in each case the boy barked, bit at the bread or dates, and spat out the mouthful. Myrtle explained that the evil spirit was supposed to pass into the food which, being blessed, had the power to destroy it. Finally the priest sprinkled everyone with holy oil mixed with water, while the three boys ran round barking and snapping at everyone in turn to entice the evil spirits to come out so the holy water could destroy them. Myrtle thought the ceremony “most impressive” and was struck by “how anxious our servants were that our dog should get the full benefit of it. Sardic sat hugging him, & implored the priest to hit him well with the stick, & half drench him with holy water”. Amice and Myrtle gave the priest coffee, and the three boys sweet biscuits, and each paid the priest PT 10 (equivalent to two shillings) for charity, together with a red silk handkerchief to wrap his holy book. It seems that Amice and Myrtle never published an account of this ceremony.

Photograph by Amice Calverley(?) (date unknown)

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

One Sunday in March 1931 Myrtle went for a long camel ride into the desert, accompanied by Sardic and two of the other servants. She told her mother that, as they were leaving the desert on their return, they noticed “paw pads in the sand, & then I saw what I took to be a jackal under a rock. It looked rather strange & when we got nearer Sardic said it was a mad dog. He had his beloved gun with him so he shot it & killed it”. Unlike the previous occasion, “he didn’t seem to be afraid of any evil consequences as it wasn’t near our habitation & it hadn’t touched us, or our belongings”.

Two years later there was a much more serious incident when one of the servants, Mahomed Abdu Rahman, was badly bitten by his camel. In March 1933 the team was visited by Elinor Gardner, professor of Geology at Bedford College, who wanted to examine some of the nearby wadis for traces of ancient flora. Elinor Wright Gardner (1892–1981) was a geologist and geoarchaeologist who worked closely with the archaeologist Gertrude Caton Thompson, and later with the explorer and travel writer Freya Stark. By the time of her visit, she was a fellow of Lady Margaret Hall, at Oxford University, and held an international fellowship awarded by the Federation of University Women.

To save time travelling back and forth from the dig house Elinor decided to camp out in the wadi “so Mahomed’s camel was loaded with the camping equipment & food, cameras etc, & Miss Gardner rode on the lady camel that Amice usually has”. Mrytle explained to her mother that “Mahomed was to stay out all night with another man, & the lady camel & her owner were to return when Miss Gardner had arrived at the place she wished to investigate & return for her the following day”. However Mahomed’s camel “got angry when the lady camel departed & wanted to follow her & Mahomed beat him to make him kneel to be unloaded & the camel turned on him & bit him in the upper arm right through to the bone. Miss Gardner tied him up as best she could & they got him on the camel & the other man brought him back to us. He was pretty bad by then so we put him in the car with Semman [another of the servants] to support him & drove to the hospital as quickly as we could. Dr Ryad attended to him at once & gave him injections & said it ought to be alright provided the camel is healthy. We reported the matter to the police & they fetched the camel & are keeping it under observation for 15 days & then if it shows no trace of hydrophobia it will probably be sold as a camel is never safe with a man once it has bitten him though it may work quite well for someone else. … Of course if it has hydrophobia it will be shot & Mahomed will be sent to Cairo to the Pasteur Institute for special treatment but this is highly improbable”. The problem seemed to have arisen because the male camel was “just at the age when male camels get fierce & this is the mating month”. Amice and Myrtle had hired the same pair of camels several times before without a problem, but had never tried to separate them; however the female camel could not remain overnight as she had a baby from which she could not be parted for too long.

The rabies vaccine had been developed by Louis Pasteur and colleagues in the 1880s. The first person successfully treated was nine-year-old Joseph Meister, who had been severely bitten by a rabid dog in July 1885. Having heard that Pasteur was vaccinating rabid dogs, Joseph’s mother begged him to vaccinate her son. Without the vaccine the boy’s death appeared inevitable so Pasteur and his colleagues decided to go ahead even though the vaccine had only been tested successfully in dogs and rabbits. Two days after he was bitten Joseph received the first of a series of daily doses of vaccine developed from the spinal cord of rabid rabbits; he did not develop rabies. A few months later a fifteen-year-old shepherd who had been severely bitten by a rabid dog was also treated successfully, and Pasteur announced the discovery publicly. People came to Pasteur from all over the world to be treated, and by 1890 rabies treatment centres had been set up in many other countries.

Paul Nadar, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Amice and Myrtle visited Mahomed in hospital in nearby Baliana two days after the incident, when they found him “better and getting on satisfactorily”; they took him some oranges and supplied his family with food whilst he was unable to work, each paying for alternate weeks. Three days later Myrtle reported to her mother that “Mahomed is recovering splendidly from the camel bite – the camel is still under observation”, and four days after that she told her mother Mahomed continued to get on very well and they hoped he would be out of hospital after a week.

Sources:

Letters: 41, 58, 84, 120, 221, 222, 223, 224.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for the photograph of Wip-wat

- the World Health Organisation and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, for information about rabies

- the Institut Pasteur and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, for information about the development of the rabies vaccine and treatment centres

- Nicholl, K., Emmitt, J., Kleindienst, M. R., Evans, S. L., and Phillipps, R., “Elinor Wight Gardner: Pioneer Geoarchaeologist, Quaternary Scientist and Geomorphologist”, Geosciences 11/7 (2021), article no. 267 [https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences11070267]

- the archivist at Lady Margaret Hall, University of Oxford, for information about Elinor Gardner