“Doctors’ parades”

Author: Susan Biddle.

“We have hospital parade most mornings. The people here get horrid boils, we usually give them a good dose of Epsom, Lysol water to wash in, & hot boracic fomentations, & trust in Allah”.

So Myrtle Broome wrote to her father in December 1929. Many of her letters home describe the patients who came to them from the villages around Abydos, often travelling considerable distances for the free treatment Amice Calverley and Myrtle provided, which was regarded as particularly efficacious.

Amice “had some hospital training during the war so she [had] a good general knowledge”, but Myrtle seems to have relied on basic first aid, common sense, and what she learnt from Amice. They referred the more serious cases to the local doctors and hospitals, often in the face of resistance from patients, who feared both their cost and the more extensive medical treatments they might receive from them.

Myrtle and Amice treated a range of ailments, most commonly cuts, burns, bites, and assorted swellings. The feast at the end of Ramadan would often result in bad indigestion when “Eppy [Epsom Salts] will be in great demand”. Epsom Salts also seem to have been given to patients with swellings or inflammation. The locals could get Epsom Salts in the village, but preferred to come to Amice and Myrtle as “they say what we give them has greater power – so we dole out Epsom & get much credit thereby”.

Their standard treatment for cuts was to remove dust and dirt with diluted Lysol disinfectant, and then bandage the wound with hot boracic lint and later iodine.

Courtesy of the Science Museum

Creative Commons licence

Myrtle frequently reports how the patients, even the youngest, bore what must have been painful treatment with great stoicism. Amongst those they treated were a woman who had cut her hand peeling onions (whose son also asked them to make the local judge release his wife from detention), a boy who had gashed his head falling down a well and who had been released from hospital before it was fully healed, and a man who had cut his shin to the bone.

One of their first patients was a teenage girl whose baby had bitten her breast causing an ulcer which needed to be lanced. They sent her to the local doctor with a note offering to do the daily dressings, but discovered the girl had been too terrified to go to the doctor. After cleaning the wound with diluted Lysol, they gave her a bottle of Lysol and a supply of bandages for future treatment, and all was well. More commonly they treated animal bites. In the first season, while Amice was away for a week, Myrtle and Nannie treated a woman whose forearm had been bitten by a dog, bathing the wound with hot Lysol and painting the tooth marks with iodine before bandaging it up.

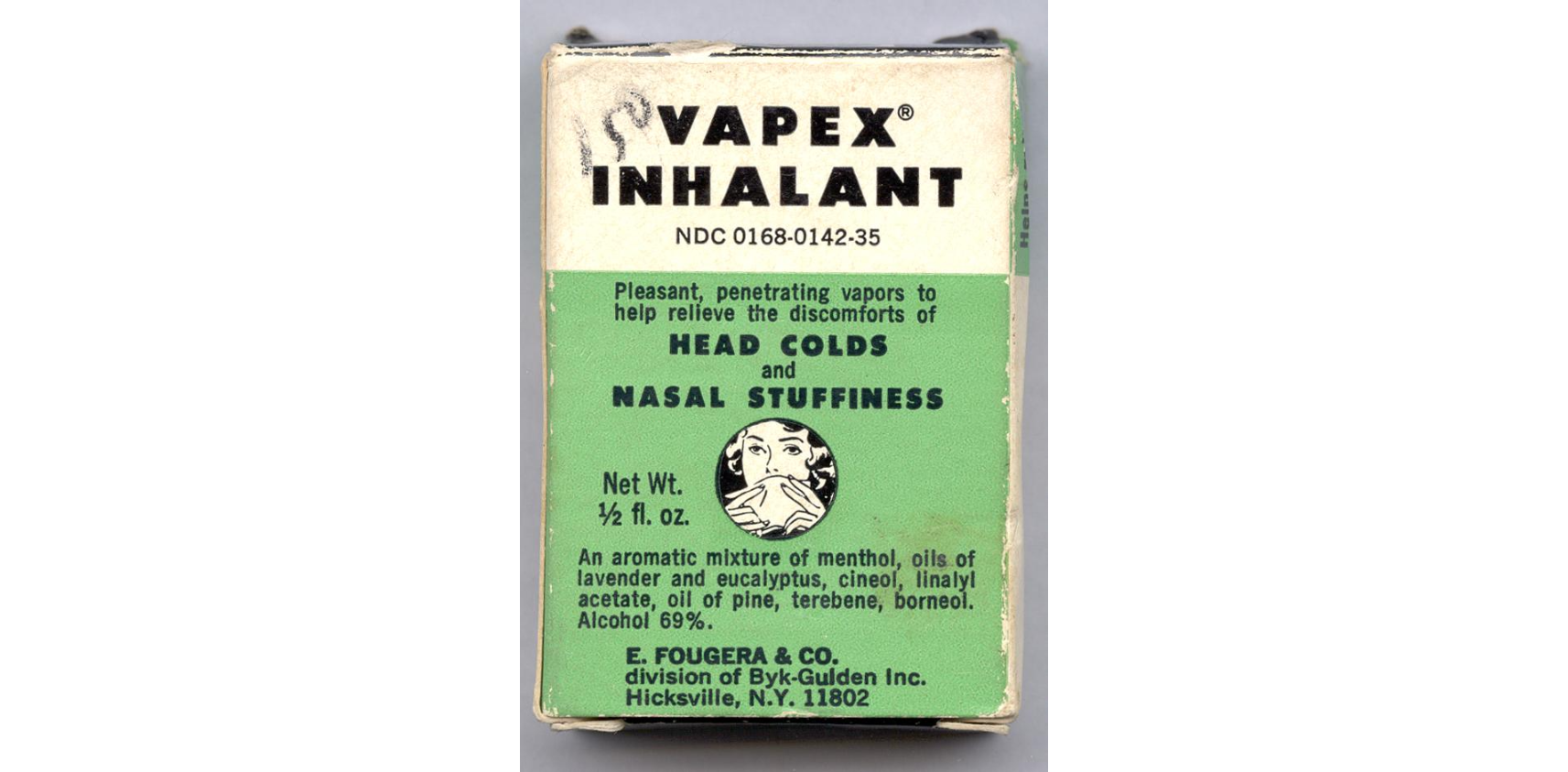

They also made occasional home visits, treating the daughter of the local Sheikh for bronchitis with hot cinnamon and sugar, aspirin, and syrup of figs (a substitute for the Epsom Salts they had originally proposed). They “also sent her a hankie well sprinkled with Vapex & a bundle of Eucalyptus leaves to be put in boiling water for her to inhale, with explicit instructions not to drink it”.

Courtesy of the National Museum of American History, The Smithsonian Institute

© Daniel Squibb

Two days later, she was much better and her father went around “singing our praises with the result that several members of his family have been coming round expecting to be cured of the most extraordinary diseases”.

Some of the cases were much more serious. In February 1930 a young man came “with the most ghastly hand I have seen” – a blister between his fingers had become septic, gathered and spread for 20 days, with the result that “the outer skin of the palm had rotted, the other skins were all separated & the tendons exposed & the stench nearly made us sick”. Amice told him to go to the doctor but the man could not pay, so they washed the hand with hot Lysol, and Myrtle suggested a bread poultice which softened the skin and enabled them to clean the hand more thoroughly when the man returned the following day. Fearing gangrene, Amice told the man to go to the local doctor and get instructions on treatment, and paid the doctor’s fee herself. The doctor approved their treatment with Lysol, iodine and antiseptic gauze dressings, and they treated him daily at dawn and sunset, with the man returning to his village 8 km away each day. When a fresh inflammation occurred, they promptly gave him “the Father of doses of Epsom Salts”. By the end of March his hand was sufficiently recovered for him to use it again if protected, and Mrs Ellen Broome, Myrtle’s mother, sent a series of gloves for him to use. Myrtle told her mother that “Mahomet of the injured hand” was “one of the best jobs I have ever helped with. … The little finger will always be stiff because the tendon is destroyed, but the way the new flesh has grown round and over is simply wonderful”.

After this success, they had “an epidemic of hands” – fortunately all less serious, including a man with a boil between two fingers and another with a poisoned thumb. They too were treated with hot Lysol water followed by hot bread poultices – and in the case of the old man with the poisoned thumb, who wore his clothes till they dropped off and brought swarms of flies with him, puffed with Flit by Nannie, the housekeeper.

Courtesy of Science History Institute

Burns were frequent. In April 1930 they treated a man whose arm had been burnt from wrist to shoulder when an evening cooking fire set light to ten of the straw enclosures in which the Egyptian farmers lived when tending their land. Myrtle was critical of the government policy which required these enclosures to be built side by side rather than in the centre of each man’s land – the practice was intended to protect from robbery, but Myrtle thought fire the worse risk. The man had burnt his arm when trying unsuccessfully to save his cow and two calves, and had also lost all his grain. After Sardic, their head servant, cut away the scorched and filthy sleeve of the man’s galabiya, they packed the burn with cotton wool soaked in Carron oil (a mixture of linseed oil and limewater) in the hope the dirt would come away when the dressing was removed.

Courtesy of the Science Museum

Creative Commons licence

They wanted to take him to the Baliana doctor, but the idea terrified the patient, and they feared the jolting of the journey would be bad for him. Instead they invited the doctor to tea and persuaded him to see the patient then. The doctor insisted the man go to the Sohag hospital, and he was sent off in a taxi at Amice’s expense – but instead returned to his village. Concerned that he would spread infection, Amice asked the local police officer to ensure the man was sent to hospital and properly treated, but the man again turned up at the Abydos dig house. Amice then sent him to the police station on a donkey, escorted by Sardic to guarantee he got there, with a letter to ensure kind treatment and a promise she would call at the hospital the next day.

In March 1931 they successfully treated a man with a leg burnt to the knee by quicklime with a new treatment about which the ship’s doctor had told them on their voyage out to Egypt. They again used Carron oil to remove dirt, and twelve hours later removed the dressing, cut away all the loose skin, and washed the burnt area with turpentine and ether, before packing it with cotton soaked in tannic acid. The tannic acid hardened the skin or flesh and avoided the need to drag off stuck dressings. Later they dressed the burn with lint soaked in Vaseline heated over a primus stove. Amazingly, he was healed within ten days; the Baliana doctor was very surprised at the speed of recovery and said he would try the tannic acid treatment himself. Two young boys whose legs had been scalded with boiling tea and soup were successfully treated in the same way; the little boy scaled with tea was notably plucky, making “the most extraordinary chokes & guggles in his efforts not to cry”. Myrtle later showed the boy scalded with soup “the little moving pictures that I bought in the street in London. He was so interested & after recognising a man jumping on a ball & a dog wagging its tail, he said to me ‘May the Lord make your life long’ it sounded so funny from a mite of 4 years old”.

Tannic acid was the treatment of choice for burns at the time Myrtle was using it, but its use was generally abandoned in the mid-1940s due to concern that it caused liver damage. Recent re-examination of the data suggests the liver damage may have been due to other causes, with the adverse effects often linked to poor quality preparations when used in high concentrations, and there has been renewed interest in the use of tannic acid to treat burns.

Some ailments were rather less serious. In January 1932 the local police officer invited Amice and Myrtle to tea and asked them to help his mother-in-law who “was suffering with her heart & had many strange symptoms that he described in the most unblushing manner”. Amice and Myrtle “concocted a lovely dose of peppermint & soda for the old lady”, and four days later the police officer tells them their dose had done her “too good – we hardly know how to take that, but we gather the old lady is better”. Other elderly ladies came asking to be made young again – Amice and Myrtle were “sorry to have to shake their faith in our skill. We can only recommend them to Allah”. In later seasons, their Sudanese guards turned back “ladies with obscure diseases or desirous of getting infants”. After Sardic’s goat delivered four kids fifteen minutes after Amice had hoped the heavily pregnant animal would produce four, Myrtle anticipated “an influx of hopeful ladies coming to ask her to use her magic on their behalf”.

Sources:

Letters 34, 39, 45, 51B, 58, 67, 74, 75, 77, 82, 86, 114, 116, 127-129, 150, 154B, 157, 160, 161, 394.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Myrtle’s letters, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Science Museum, London, for images from their online collection

- the National Museum of American History, The Smithsonian Institute, for an image from their online collection

- the Science History Institute, for the image of the Flit Manual Hand Sprayer

- Halkes, S.B.A.; van der Berg, A.J.J.; Hoekstra, M.J.; du Pont, J.S.; Kreis, R.W. (2001). “The Use of Tannic Acid in the Local Treatment of Burn Wounds: Intriguing Old and New Perspectives”, Wounds 13, 144–158.