Learning Arabic – 3

Author: Susan Biddle.

This is the third of a series about Myrtle Broome’s experience of learning Arabic. This post is the first of two looking at Sheikh Sarbit, her first Arabic teacher, and focusing on her lessons.

When Myrtle Broome and Amice Calverley decided, at the start of their third season working together at Abydos, to take formal lessons in writing Arabic, they turned to the local schoolmaster for instruction. He came to the dig house at Arabah el-Madfunah every Saturday evening to give them one-hour lessons.

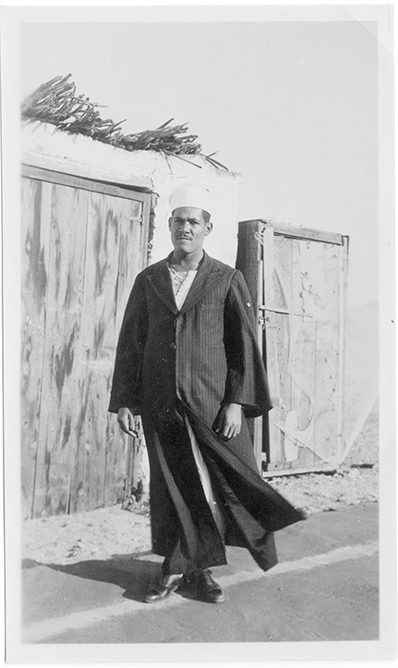

Following their second lesson in December 1931, Myrtle described their teacher to her mother: “he is a very fine handsome young man. He evidently considers it a great honour to come to teach us, & I think he puts on all his ceremonial robes one over the other in order to be equal to the occasion – he fair rustles”. From the start Myrtle looked forward to her lessons, which she found amusing, telling her mother that the schoolmaster “is … very patient” and “he never gets the least bit annoyed when I keep repeating the same stupid mistake”.

The schoolmaster was proud of his pupils’ progress, which reflected well on him as a teacher. Two months after their first lesson, the local Coptic priest called during a lesson and Myrtle was asked to read some Arabic to him. The priest “was inclined to be very critical & the schoolmaster was simply furious. He said it was very wonderful that we could read at all after so few lessons”. Myrtle explained to her mother that “of course the Coptic priest is very jealous that we have the schoolmaster & not him to teach us & there is great rivalry between them. The schoolmaster completely squashed the Coptic priest by flourishing my very best Arabic writing under his nose”.

It was not until January 1932 that Myrtle discovered the schoolmaster’s name, which was Sarbit Abdullah Tayia, though she always addressed him as Sheikh Sarbit. She told her father: “he is certainly a very good teacher, it is very different being taught by someone who is so used to teaching. They realize that one knows nothing of the subject & are careful to explain by easy stages, whereas someone not used to teaching is unable to realize one’s state of complete ignorance”.

When the school term ended, Sheikh Sarbit returned to his own village near Sohag – during term time, he lodged with the omdah [village headman] of Beni Mansour as his own home was more than 40 miles away. Their in-person lessons were perforce discontinued during the school holiday, but instead Myrtle wrote letters to the schoolmaster and posted exercises to him for correction, and this practice continued throughout the summer while Myrtle was in England. When she had proposed this to Sheikh Sarbit, he was “very delighted at the suggestion”, and she thought he “look[ed] forward to receiving letters from England with great pride”.

At the start of the next season, “the schoolmaster made a state call with his two undermasters & they all complimented me on my efforts at writing Arabic during the summer”. The lessons resumed, and at the first one Myrtle gave Sheikh Sarbit a pen which “was quite the right thing. He was delighted, he kept on murmuring expressions of gratitude all the time I was showing him how to fill it & I felt so embarrassed that I nearly split the ink”. She had clearly taken some trouble over this present, explaining to him that “the man in the shop had seen one of his letters so as to select the right nib”. When she asked him to try the pen, “he wrote ‘I am exceedingly grateful’ & the pen suited his hand exactly”.

Sheikh Sarbit was a kind and considerate teacher. When Myrtle made mistakes, rather than scold her, “he looked very hurt”. When a lesson coincided with Myrtle starting a very heavy cold, she told her mother: “my head felt like a blob of cotton wool & the things I wrote for dictation were most surprising. The Sheikh was most sympathetic & advised me to wrap my head up well & put wool on my chest”. She “took the latter advice but not the former. He really was most tactful during the lesson, he could see I wasn’t at all up to the mark, so instead of looking pained & surprised when I missinterperated (something wrong with the spelling here?) his best efforts he tried to help me over the difficult parts by whispering the letters under his breath after making the noise & trying to look as if he wasn’t doing it – wasn’t it nice of him”.

He could however occasionally be more robust. In January 1934 he “decided that it is time for me to learn to write the rapid Arabic handwriting”. This required Myrtle “to go back to the beginning & learn the alphabet again; it is about as different as our handwriting is from print & 10 times more difficult to make out if badly written”. He brought her “the school copy book with rows of pot hooks & hangers”, which she solemnly copied out but found it rather a struggle. She told her mother that “having got used to the other [i.e. printed writing] I find it very difficult to change my style”, but “when I remarked to Sheikh Sarbit about the difficulty, he said I must pull together my strength, or, as we should say, ‘pull up my socks’”.

Although Myrtle said that “usually he takes my most brilliant successes as a matter of course”, she realised that her progress in Arabic was a source of great pride to him. In February 1933 he brought to meet her a new undermaster, who had come from a village near Cairo. She thought that the Sheikh “wanted to show off my writing & reading to this newcomer. …. From his description to the other master I have made unheard of progress in writing stories in Classical Arabic”. Myrtle thought that “what impressed the new master most was my keeping up my lessons during the summer in England & having my lessons corrected here in Abydos by the schoolmaster. He fairly gasped with amazement, evidently he had never heard of such a thing being done before”.

At the start of the fifth season Sheikh Sarbit was ill, so Myrtle was instead taught by his under teacher, Sheikh Jed el Karim. Both Sheikhs visited her the day after Sheikh Sarbit’s return to work, when Myrtle thought that “the poor man still looks very ill. He seems to have had a touch of sun, then got a chill, & that led to flu. They kept him in hospital for some time”. He was nevertheless eager to hear how lessons had gone in his absence, so she read aloud the story she had written in Arabic. Sheikh Sarbit quickly reasserted his authority as head teacher by being very critical of Sheikh Jed el Karim’s corrections.

Sheikh Sarbit promptly resumed his role as Myrtle’s teacher, although Sheikh Jed el Karim “was very reluctant to relinquish his duties”, and sometimes both Sheikhs attended the lessons, which led to some competitive correcting. On one occasion, when Sheikh Sarbit had corrected the story Myrtle had written in Arabic, “he passed it over to Sheikh Jed el Karim for him to read. He studied it very attentively & then called Sheikh Sarbit’s attention to a certain phrase & said ‘wouldn’t this be better expressed in such & such a way’. ‘Oh’ said Sheikh Sarbit in a very superior way, ‘I think it is better left as it is because it is the English way of expressing it’. I had quite a job to keep a straight face. I expect Sheikh Sarbit poses as an authority on English”.

Myrtle was very sorry when in March 1934 she was “bereft of my nice schoolmaster. Sheikh Sarbit has been removed to a village near his home”. She was “very glad for his sake, as he was very lonely & unhappy so far away from his own people, but of course I miss him very much”. She took his photograph “& gave him prints as a parting gift … he was delighted”. He had very little notice of his transfer and came to say goodbye only on the day before he left, so Myrtle had no opportunity to pay him the balance of his salary, which was about 12/– . She “thought the occasion called for a little present as he had been teaching me for three years, so I put two pound notes in an envelope & wrote a letter asking him to accept the gift with my congratulations etc all in my very best classical Arabic hand writing. He is generally very reserved & uneffusive but I suppose the unexpected generosity proved too much for him & he wrote a wonderful letter of thanks that might have come out of the Arabian Nights, it was a masterpiece of clever phrase making, in three words he expressed a sentiment that would fill three lines in clumsy English”. He told her: “My gratitude to you is as a thousand gratitudes, even so are my regrets at being separated from you. And in conclusion I send you fragrant greetings & sincere regards”.

Sources:

Letters: 153, 160, 161, 163, 165, 167, 180, 181, 185, 196, 197, 204, 217, 242, 245, 248, 249, 253, 257, 259, 275, 276, 277

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog