Music – 2 (1930–1937)

Author: Susan Biddle.

This post in the second of two looking at Myrtle Broome’s enjoyment of music, particularly musical entertainment provided by Egyptian musicians in a variety of situations. This post focuses on the music they enjoyed at festivals and on special occasions in the later working seasons.

Both Myrtle Broome and Amice Calverley were music lovers as well as artists. Myrtle was the daughter of music publisher and cellist Washington Herbert Broome, and Amice had studied music at the Toronto Conservatory of Music in Canada and at the Royal College of Music in England.

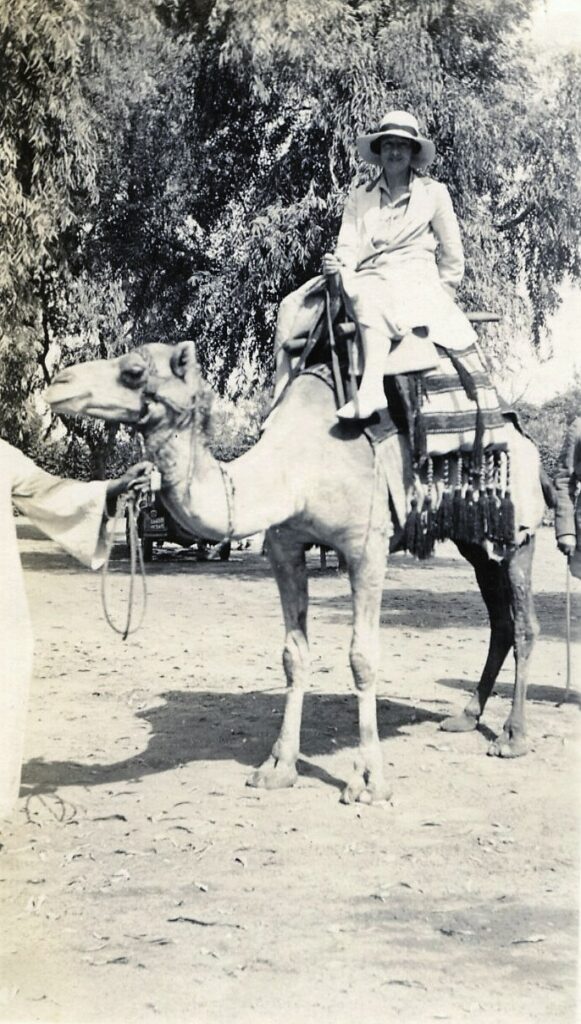

As well as the musical entertainment enjoyed in camp described in a previous post, Myrtle and Amice attended many local festivals which included music. In April 1931 they went by camel to the early morning part of a local festival at Beni Hamil. After watching the camel racing and riding displays, they went to see the horses which were “pure Arabs. They had gorgeous saddles, many covered with plates of pure gold, & they had their own music, wild shrill pipes, like the squealing of stallions played to the rhythmic beating of drums. This special music is never played except for the horses & they love it. They prance & toss their manes & are never still for a moment while it is being played, but when it stops they stand as quiet as anything. … It was pretty to watch the horses dancing, their movements guided by the long lances their riders carried. They circled & pranced & reared & knelt, & all the time the men playing the pipes & the drums danced in & out with them”. The music had an unexpected effect on their own camels. Myrtle told her mother: “It is the most contagious rhythm one can imagine, even the camels got affected by it. Amice’s camel was a lady & evidently very musical, she swayed her head from side to side & took first a step to the right & then a step to the left in perfect time to the music – it was funny & a little disconcerting for Amice as the camel next her was doing the same thing & occasionally they bumped – however nothing would stop her while the music played”.

Photograph by Amice Calverley

Bushey Museum & Art Gallery

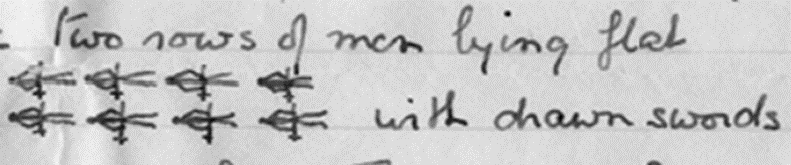

Each year there was a festival at Qena in honour of Sheik Abd el Rahim, a Moroccan who founded a Sufi centre in Qena in the twelfth century. On his death in 1195, a mosque was built above his tomb and this became a place of pilgrimage. Myrtle and Amice first attended this festival in January 1930 when they “saw a most extraordinary sword dance. There were two rows of men lying flat on the ground … with drawn swords laid blade downwards across their tummies, the drums & pipes played weird exciting music, & a man supported on either side by two other men leapt from man to man alighting on the swords each time”.

In November 1934 they attended another festival at Qena and “stopped to listen to a group of native singers & among them [Myrtle] recognized our strolling player who comes to sing us the songs of Abu Zayd, & play the native fiddle. He was delighted to be noticed & came to shake hands with us, & he has promised to come to Abydos to sing for us again”. The following February the musician made good his promise and played some more songs of Abu Zayd for the Abydos team and their visitors, Stephen Sherman and his wife, who were relaxing at Abydos at the end of a strenuous season working with J. D. S. Pendlebury at Amarna, and “enjoyed the entertainment very much”.

Photograph by Myrtle Broome

Bushey Museum & Art Gallery

In January 1937 the travelling musician was back with them, accompanied by his son-in-law and two nephews. Myrtle told her mother: “the son-in-law played a second fiddle & the eldest nephew, a lad of about 18, played the drum & the younger one had no instrument but sang beautifully”. After some more of the traditional songs of Abu Zayd, “the old man exchanged his fiddle for the drum & the two boys sang a duet in our praise with numerous topical allusions. It was all in verse & had a jolly chorus in which they all joined. It reminded me a little of the sea shanties, there were roars of applause from the native audience, it went something like this, ‘Very great are the ladies, there are none like them in the land’, sang one boy, ‘they are more important than the Prime Minister, no man dare aspire to them’ sang the other boy & so on. We cannot think how they managed it. They never faltered & rhyme & rhythm were perfect”.

They noticed the boys admiring a tiny tree with little candles on it which was part of their Christmas decorations, so Amice lit the candles and turned the lamp low so they could appreciate the tree better. The musicians were delighted “& the old man said, ‘we will make a song to the tree’ so one boy sang ‘do you see the wonderful tree oh my brother?’ & the other answered ‘I see it indeed & it has 8 lighted candles’ & then the first sang ‘From whence came this tree oh my brother?’ & the second replied ‘I know not. May be from Cairo or Alexandria’. Then the first rebuked him saying ‘Oh thou of little intelligence, such a tree as this must come from a foreign land’ and they kept this up all the time the candles were burning. They sang it to the tune of their previous song & the wonderful thing was that it was all in perfect verse, the end of each line rhymed & it was all done on the spur of the moment. You can imagine how delighted we were”. Myrtle and Amice produced some crackers left over from Christmas “& told [the musicians] to pull one. You should have seen the consternation when it went off & then the eagerness to pull the rest to hear the exciting bang & the thrilling hunt for the contents”. Myrtle thought “it was the most successful evening we have ever had”.

A fortnight later the young King Farouk, his mother, and four sisters visited the temple. On Amice’s recommendation to the master of ceremonies, the music during the King’s lunch was provided by the travelling musicians. Myrtle told her mother that “they sang a special song of their own for the King & he was so delighted that he gave them £5. You can imagine the state of excitement they have been in ever since”. A few days later “the rubaba [fiddle] player came round to tell us that the Omdah [village headman] had got an illustrated newspaper, & there was a picture of them playing in front of the King”. The fiddle-player was very impressed by this publicity, telling Myrtle that “there was the whole storey of it written out so that all the world could read it”. Three weeks later Myrtle and Amice had another “visit from our minstrel friends. They came to say how grateful they were to us for arranging for them to perform during the King’s visit. … They were all dressed in new galabias, they had evidently been spending the King’s bounty. The old fiddler had made his eyes up with black eye paint like a naughty lady & looked very dashing. He regards himself as a very great personage now”.

Such a high-profile performance and resulting fame seems a fitting finale to the musical entertainments which Myrtle had enjoyed throughout her eight seasons at Abydos.

Letters: 54, 132, 302, 324, 391, 393, 396.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for Myrtle Broome’s photographs

- the Artefacts of Excavation project, for the details of the team working at el-Amarna during the 1934–1935 season