Myrtle and the “Boy King” Tutankhamun

Author: Susan Biddle.

To mark the anniversary of the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun by Howard Carter and his team, this post looks at Myrtle Broome’s encounters with some of the objects found in the tomb and with some of the people working on them.

By the time Myrtle Broome arrived in Egypt to work with Amice Calverley at Abydos in 1929, it was seven years since Tutankhamun’s tomb had been discovered. The tomb had been mostly cleared, with the exception of the removal of the shrines, but work on conserving the artefacts was ongoing.

When Myrtle first arrived in Cairo in October 1929, one of the first people whom she met was “a famous analytical chemist, … employed in the treating & preserving of all Tut’s things”. This was Alfred Lucas. In December 1929, Lucas visited Myrtle and Amice in Arabah el-Madfunah for five days to advise them on cleaning the painted surfaces in the Temple of Seti. Myrtle told her mother: “He is a nice man. It is an awful feather in our cap to get him out here … He is now finishing his work on preserving all Tut’s stuff”.

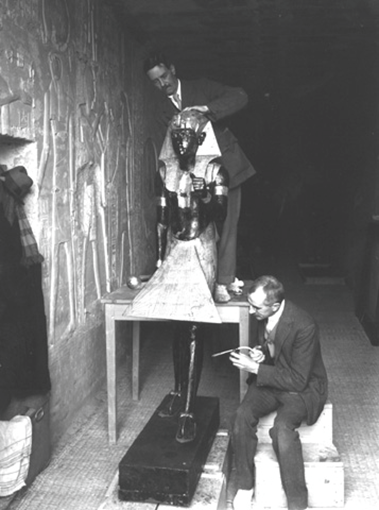

In April 1923 Lucas had become the chemist to the Department of Antiquities, which seconded him to Howard Carter to work on the cleaning and conservation of objects from Tutankhamun’s tomb within a month of the discovery. Lucas worked with Carter for nine seasons, and together with Arthur Mace, established a laboratory in the nearby empty tomb of Seti II (KV15). There they cleaned the finds and did essential conservation to enable the objects to be transported to Cairo.

Photograph by Harry Burton (p0493)

© Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

In an April 1923 article in The Times, Lucas explained that many objects needed to be cleaned, strengthened, and repaired before they could be photographed, recorded, packed, or taken to Cairo. Any mistake in treatment could ruin them and would probably be irreparable. The first step was to remove superficial dust, which was usually done with a small pair of bellows or gentle use of an artist’s brush – a duster might catch in loose gold and cause damage. They had to analyse the nature and properties of all the constituent materials, such as wood, gilt, paint, plaster, inlay, and cementing material, before risking water to treat any object. Lucas’ private notes of his conservation work show the care he took and some of the techniques he used. Seti II’s tomb was well-insulated and secure, and when the temperature exceeded 100˚F [37.8˚C], Lucas and Mace could work in the open space outside the entrance. Lord Carnavon told The Times’ journalist Arthur Merton that “even from the outside the smell of chemicals is perceptible, and on entering, the odours of acetone, collodion, and other unpleasant things which the experts seem to enjoy using are very strong”. Lucas’s skill was recognised by Flinders Petrie in a letter to Percy Newberry on 17 January 1923, when he wrote: “we can only say how lucky it is all in the hands of Carter and Lucas”.

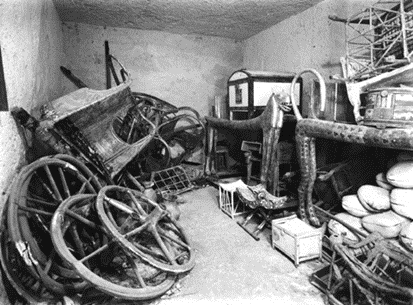

Photograph by Harry Burton (p0517)

© Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

Off duty, Lucas was a devotee of crossword puzzles, then something of a novelty. The Daily Telegraph was the first British broadsheet newspaper to publish a crossword puzzle in the United Kingdom in 1925; The Times did not follow suit until 1 February 1930. When during Lucas’s visit a bundle of Daily Telegraph crosswords fell out of the Observer newspaper which Mrs Broome forwarded to Myrtle, Myrtle told her mother: “there were hoots of joy from both Beazley [the third European member of the team at that time] and Mr Lucas. They are both enthusiastic about them, they have been busy with them ever since dinner”.

Lucas treated Amice and Myrtle to dinner in May 1930, when they were in Cairo at the end of the season, and Myrtle was gratified that he thought her collection of amber was “really very good”. They met again in Luxor in December 1930, when he came to dinner at Chicago House while Amice and Myrtle were visiting to discuss the Oriental Institute’s colour recording methods. Myrtle feared that Lucas was “of too retiring a nature to unbend in this atmosphere”, which she and Amice found very formal, but looked forward to seeing him again.

Amice had hoped to persuade some of the Chicago House staff to return with them to help with the photography. Myrtle told her mother that Amice “has hopes of getting Burton. He is the man who took all the Tut things for the London Illustrated”. In this Myrtle thought Amice was “a little optimistic”, and was proved right.

Photograph by Harry Burton (p0753)

© Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

Photograph by Harry Burton (p0156)

© Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

Unsurprisingly, Tutankhamun was a subject of general interest at the time. In March 1932, when visiting a local sheikh at the holy tomb of one of his ancestors, Myrtle met the omdah [headman] of the nearby village. She found him well-educated and even able to speak a few words of English; by this time Myrtle had been learning Arabic for fifteen months and told her mother: “we had such a long conversation. … We discussed the merits of modern doctors compared with the doctors of Tutankhamun’s time”.

When Myrtle and Amice arrived in Cairo in November 1932, they spent a morning at the Cairo Museum where Lucas showed them “all the latest Tut things that he has been restoring in the Museum. The gold shrines are marvellous. We were able to go inside them & examine them closely. We also saw the model boats, jewel cases, furniture, chariots etc”. Myrtle told her mother that “the various parties of tourists who were going round on their own, or with dragomen [interpreters], were green with envy”.

Myrtle spent the next two days with Reginald (“Rex”) Engelbach, Chief Keeper of the Cairo Museum, who was “very busy trying to find out how Tut’s horses were harnessed to the chariots”. He was having a small model made, and Myrtle, a keen horsewoman, helped him with the reconstructions. Myrtle explained that they had “all the actual fragments of the ancient harness that remain to see if we can discover how they were buckled or tied on – it is very exciting. … We are making a pattern set of harness from the reliefs of chariots & horses of that period, & when we have worked it out, it will be sent to a saddler & he will make a set of harness to fit the horses for the model”. She made a stuffed horse from the rag bag of Rex Engelbach’s wife Nancy, “to experiment on until the model horses are ready”; this had “caused a lot of fun … He is most accommodating as one can stick as many pins in as one likes”.

Photograph by Harry Burton (p0012)

© Griffith Institute, University of Oxford

The Engelbachs took Myrtle to dinner at the Khedival Hotel at the invitation of John Pendlebury, whom Myrtle thought “very nice”. Pendlebury was then directing the Egypt Exploration Society’s excavations at Akhenaten’s capital city at Tell el-Amarna. He was in Cairo looking through objects from Tutankhamun’s tomb for re-used items from Akhenaten’s reign in the hope that these could shed light on the complex co-regencies of the period.

Tutankhamun made a final appearance in Myrtle’s letters in December 1935, when she wrote to her mother asking whether she had seen the notice of the death of Professor Breasted, founder of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, which was the co-organiser of the team with the Egypt Exploration Society. Professor Breasted had visited Abydos the previous month when he “seemed very satisfied with the way the work was being done”. She told her mother that they were “all very distressed at the news, especially as he was our guest so recently”; they had read of his death in The Egyptian Gazette, which “reminds its readers that he was present at the opening of Tutankhamun’s tomb, & hints again of the curse being the cause of the death of all who assisted at the opening”.

Sources:

Letters: 31, 44, 88, 94, 95, 178, 194, 195, 351, 356.

Newberry Correspondence – Petrie, (Sir) William Matthew Flinders NEWB2/582, Letter 37/85.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, for access to their Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation collection of archives including Lucas’s conservation notes and Burton’s photographs, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Artefacts of Excavation project, for biographical details for Alfred Lucas, Howard Carter, Arthur Mace, Flinders Petrie, Percy Newberry, Harry Burton, Reginald Engelbach, and John Pendlebury

- the Theban Mapping Project, for information about the tomb of Seti II in the Valley of the Kings (KV15)

- the Egypt Exploration Society, for information about Tell el-Amarna

- Information on Alfred Lucas from: Brunton, G., “Alfred Lucas 1867–1945”, Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte 47 (1947): 1–6; Edwin, H. H., “Alfred Lucas. O.B.E, F.R.I.C, F.S.A.”, Bulletin de l’Institut d’Égypte 28 (1945): 163-165; Gilberg, M. “Alfred Lucas: Egypt’s Sherlock Holmes”, Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 36.1 (1999): 31–48; James, T. G. H., Howard Carter: The path to Tutankhamun (rev. ed. 2001); Hoving, T., Tutankhamun: The Untold Story (1978)

- Information on John Pendlebury: Grundon, I., The Rash Adventurer: A Life of John Pendlebury (2007)