Water – 2

Author: Susan Biddle.

This post is the second of four relating to water. The first in the series focused on personal washing arrangements. This second post looks at the team’s arrangements for washing clothes, haircuts, the “facilities” at the Temple of Seti I and the occasional opportunities for enjoying a swim (despite sharks).

Getting one’s hair cut was something of a rare event during the working season at Abydos. When Amice Calverley joined Myrtle Broome at Marseille in October 1929, en route for their first season working together, Amice’s first priority was to get her hair cut. Her brother Hugh probably regretted not doing the same. Three weeks’ later Myrtle told her mother that Captain Hugh Calverley returned from a trip to the Baliana blacksmith “absolutely cooked & shouting for a hair cut at once”. Since Amice was bathing, he “seized on [Myrtle] for the job”. She rose to the challenge, telling her mother: “it was such fun. He has curly hair & I was able to make a very good attempt. He said it felt cooler & that’s all he cared about”. Myrtle herself waited until she was back in Cairo at the end of the season for a trip “to the hair dressers [for] a trim & a wave”. Whilst in Abydos, she made do for hair washing with a kettle of hot water, brought to her by Abdullah, the youngest servant. Other members of the team resorted to more extreme measures. In 1937 two American artists who were temporarily seconded to the team were unable to appear during King Farouk’s visit to the temple as “they had decided to cope with the lack of barbers (European) by shaving their heads!!! & wearing a sort of turban to hide their nakedness. They had got hold of the idea that this would strengthen the roots of the hair & prevent baldness later. Of course they could not appear before Royalty in that condition so had to remain in seclusion at the house”.

At the Temple of Seti I, the team had “a little tent fixed up with a sand closet & wash bowl”. Myrtle explained to her mother that “all the servants & guards watch our comings & goings. The other day Miss C. asked where I was & was informed that I was in the ‘house of good behaviour’”, which Myrtle thought was “the most poetic description of an unromantic necessity that I have ever heard”. By a later season this necessity seems to have acquired another euphemistic name, Myrtle telling her father that “the bees are building over the door of our ‘Here it is’. They buzz round our heads when we go in & out & we have to be careful we do not sit on one, but they also provide us with entertainment so we don’t really object to their activities”.

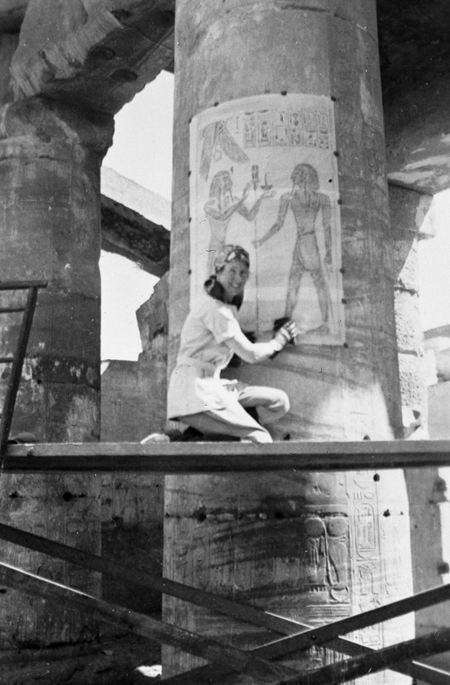

Particularly at the end of the season, it could get very hot in the temple. Myrtle and Amice needed to rinse their hands frequently in cold water to keep them cool so as to avoid smudging their painting. In April 1929 it was 98° F (= 37° C) in the shade before midday, so Myrtle told her mother: “I had a bowl of water on my guntera [scaffold] to keep cooling my hands. I got tired of climbing down every half hour or so to rinse them so got Sardic [the head servant] to bring me a private bowl of my own”.

© Myrtle Broome (date unknown)

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

They also needed water in the temple for cleaning the walls. At the start of the second season, Myrtle told her mother: “we are cleaning the walls ready for the colour work, the upper scenes are badly discoloured with smoke. The temple was used a lot in Early Christian times as a dwelling & their cooking fires did a lot of damage to the walls”. However she was able to report that “we have got quite a lot of the outer coating of smoke & dirt off by washing carefully with soft sponges & clean water, we keep two men constantly busy washing the sponges for us”. Amice described this as “bathing the King Seti & his gods – & very dirty they were too!”.

Although the heavier washing was done for them by local women, Myrtle and Amice washed their more delicate garments themselves on market day, which was their day off from work in the temple. Myrtle explained to her mother in October 1929 that they “had tubs outside in the shade of the house and Abdullah fetched hot water for us & carried the bowls of wrung out clothes for us to hang them on the line. It was a wash de lux”. On another market day, “Amice petroled some frocks & coats”. This was a recognised method for removing grease from clothes in the 1930s. Readers of Agatha Christie may remember that at the start of her 1923 short story The Kidnapped Prime Minister, the fastidious Hercule Poirot was too busy mopping his suit with a small sponge soaked in benzine to pay attention to his side-kick Arthur Hastings. Today’s “dry cleaning” has replaced petrol with non-flammable liquids. Underwear was washed daily, Myrtle explaining to her mother that when she had her evening bath, “I wash my vest & stockings at the same time”; at least during the hot weather, “the things I wash are dry before bed time”.

Driving back to the UK through the Greek mountains at the end of their final season, Amice and Myrtle had a scenic wash day. Myrtle told her mother that “Amice and I had a laundry beside a fast running stream & washed all our dirty clothes & dried them on the rocks while we had our lunch. We folded them before they were quite dry & they looked as if they had been ironed & smelt of flowers. There were bushes of pink oleanders all along the bank of the stream, so you can imagine how lovely it was”.

In the dig house ironing was done with an iron heated on the primus; Nannie heated the iron but Myrtle preferred to do the ironing herself, telling her mother: “I dare not let Nannie do it as her ironing is awful”. By contrast, when sailing to Egypt in October 1934 on SS Tuscania, Myrtle indicated to her mother that “there is a lovely electric iron in the Ladies Room. I used it yesterday to iron the brim of my shady hat which had got a little dented in the hat box”.

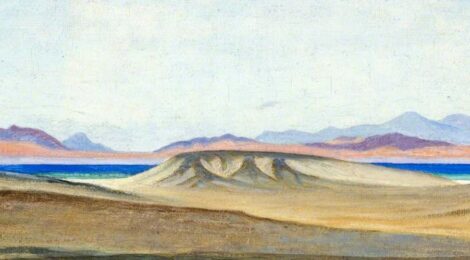

At the end of the third season, Amice and Myrtle took a brief holiday on the Red Sea coast, driving across the Eastern Desert in Amice’s Jowett car. After a two-day drive, they reached the Red Sea which “was glorious. Golden sands with strange shells, a fringe of mountains of red granite, purple porphyry & orange sandstone in the background & then the deep blue sea, paling to delicate green over a white coral reef”. They “drove along the sea shore & made our camp among the sand dunes. … In less than five minutes Amice & I were prancing over the coral reef in bathing dresses (adapted to Arab ideas of decency) the sea in the shallows was as hot as one usually has for a hot bath at home”.

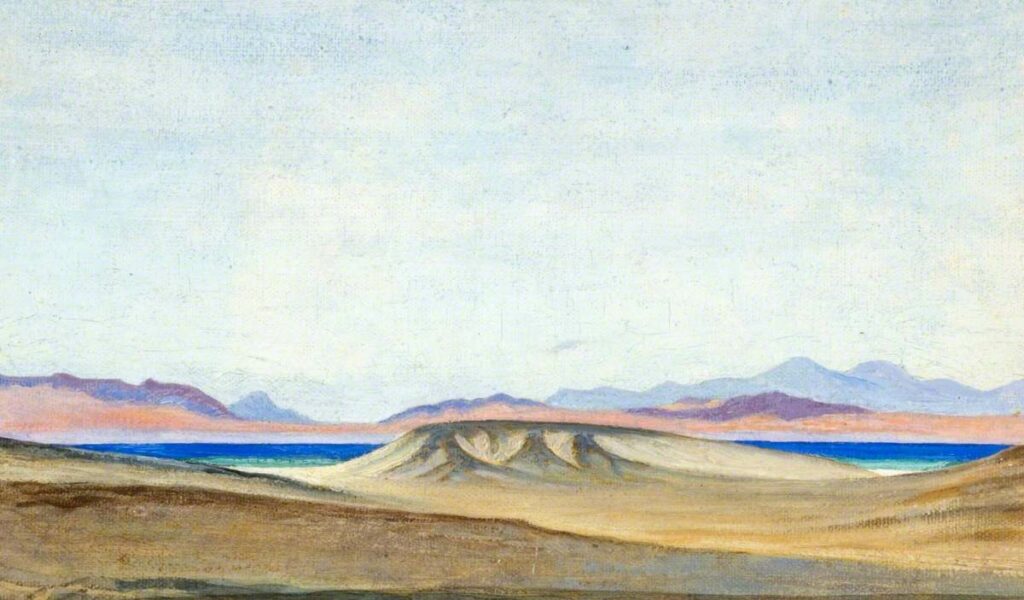

© Myrtle Broome (date unknown)

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Swimming in the Red Sea was not without some risks. On their first trip, they had to “clear purple jelly fish out of the way”. Four years later, it was sharks which were the concern. In March 1936 Amice and Myrtle again drove to the Red Sea, taking with them “bathing things, & old shoes to paddle in on the coral reef”. After another two day drive, they arrived “on the seashore at 4.30 & by 4.35 we were in the sea. It was wonderful. Warm sea. Shelly beach surrounded by a fringe of rugged mountains, it did not seem like a terrestrial landscape, we felt we must be in the moon or Mars”. Myrtle recounted to her mother: “we played about on the shore till dusk collecting shells, coral etc, also some sharks’ teeth”, but reassured her that “we did not venture out beyond 3 ft”. The following day they drove north along the coast to Hurghada, where the Shell Oil company operated a number of oil wells. There Myrtle and Amice were able to swim in “the Company’s bathing pool which was in deep water & was surrounded with wire netting to keep sharks out”. They “had a glorious swim”, having the pool to themselves. They then continued on up the coast to a marine research station, where they “were made very welcome by Dr Crossland & his wife”. Dr Cyril Crossland, a zoologist and explorer who had previously run an oyster farm north of Port Sudan, had established this marine biological station in 1930 at the request of the Egyptian Government, and lived there with his Danish wife Hildur and their son Ingolf until 1938. The following morning Myrtle and Amice “saw the dawn break over the Red See then donned our bathing dresses & were soon splashing in a sea that looked as if it was made of rainbows”. Later that morning another visitor at the marine research station, a Royal Naval Reserve officer who was charting the coral reefs, invited them to join him on a boat trip to take soundings. Unlike the officer, Myrtle and Amice understood the Arab boatman’s dialect and “got him yarning & telling tales of sharks & he showed us two scars on his legs where a shark had got him once, you can imagine what fun we had”.

Sources:

Letters: 27, 34, 36, 79, 88, 96, 97A, 182, 191, 292, 316, 370-373, 389, 392, 393, 396, 413.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for Myrtle Broome’s painting and for access to Myrtle Broome’s photograph albums

- Gardiner, J. S., “Dr. Cyril Crossland”, Nature 151 (1943), 162–163 and The National Archives, for information about Cyril Crossland