Water – 3

Author: Susan Biddle.

This post is the third of four looking at water, and focuses on its management and distribution, from the Nag Hammadi dam to the dig house garden, and in both the Nile Valley and the Eastern and Western Deserts.

Myrtle Broome’s letters to her parents often include references to irrigation and water supply, ranging from the industrial scale to the domestic level.

In January 1930 Myrtle and Amice were invited by Mr Ellison, the chief engineer, to see the new dam being built across the Nile at Nag Hammadi. Myrtle told her mother that the barrage “is a marvellous engineering feat, but in its present state hardly a thing of beauty, but it is going to give Egypt many more acres of cultivated land. We had a special thrill, Mr Ellison took us over in the bucket. This is an iron cage which is lifted up to a great height & passes along a wire right across the Nile. It is said to be the biggest thing of its kind in the world. It certainly was great fun seeing everything from so far above. We saw the pile driving etc & returned in a steam launch”.

At the end of the year they returned to Nag Hammadi when Mr Ellison invited them to attend the barrage opening ceremony with King Fouad. On 19 December 1930 they drove over in “Joey”, Amice’s Jowett car, “dressed in all our best, white gloves in our pockets & linen dust coats to protect our finery. Sardic [their head servant] sat in the back with clean white turban & galabia”. They arrived about 10 a.m. to find “a magnificent tent had been put for the King to give his address in, it was made of lots & lots of different coloured material sewn together in elaborate patterns, inside was a gold throne for the King & rows & rows of gold chairs for officials. Of course the address was in Arabic, so we just had a look at the tent & spoke to a few people we knew, & then went out onto the Barrage with Mr & Mrs Ellison. In a little while the King & his many retainers arrived, & then he proceeded to move the lever that raised one of the sluice gates & declared the Barrage open. That important part of the ceremony being concluded, he then embarked on his private yacht that was awaiting him, & passed through the lock”.

Photograph from an album commemorating the opening of the Nag Hammadi Barrage in 1930

© Mary Evans Picture Library / Pharicide

As Ellison explained in a January 1931 paper for the Institution of Civil Engineers, the Nag Hammadi barrage was intended to manage to best advantage the increased volume of water stored by the Aswan dam which was raised by nine metres between 1929 and 1933. When completed, the Nag Hammadi dam fed an irrigation system which enabled year-round cropping of 320,000 hectares. In 2008 the 1930s dam was replaced by a new barrage 3.5 km downstream. Unlike the 1960s Aswan high dam, the 1930s dams and barrages did not entirely control seasonal flooding of the Nile which brought valuable nutrients to the Nile. In April 1930 Myrtle told her mother: “the Nile Valley is now a yellow strip of golden grain. We have watched it change from the waters of the inundation, to black mud, to vivid green & now to light yellow”. Less appreciatively, Myrtle reported in November 1936 that “there was a very high Nile this summer & the floods have not quite subsided yet, so we are being rather bothered with mosquitoes”.

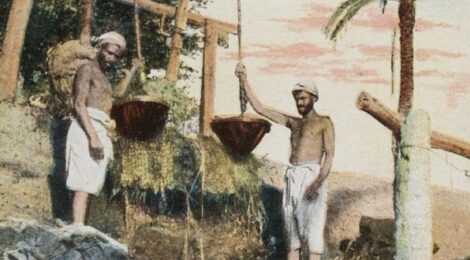

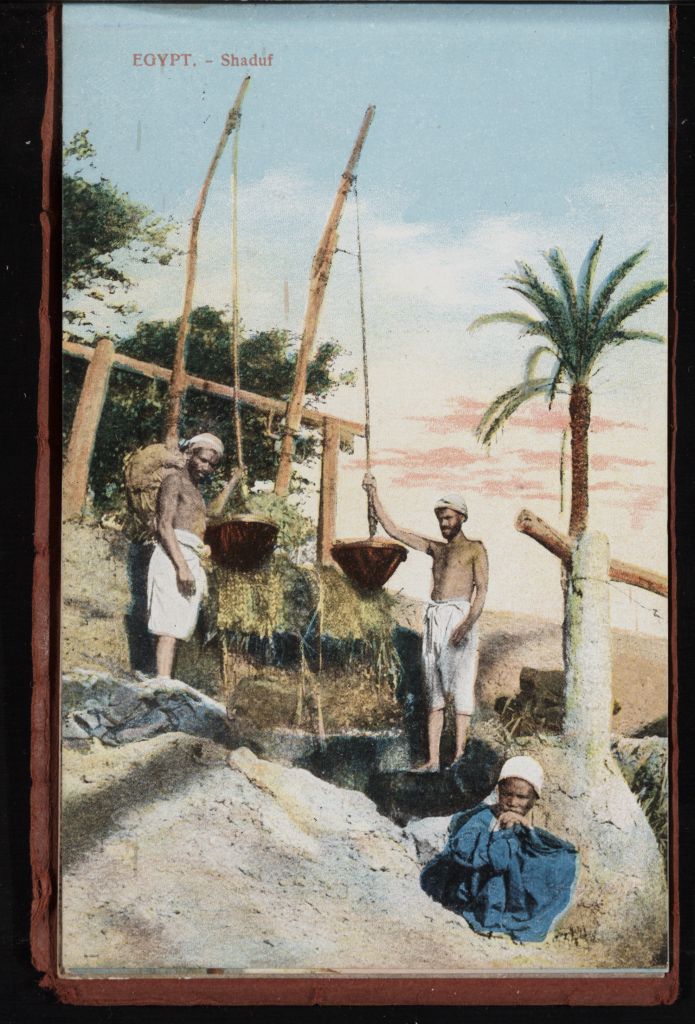

The water was distributed across the cultivated area by canals. Riding camels through the cultivated ground on their days off, Amice and Myrtle “saw [the villagers] filling the little channels with water from the shadoof”.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:EGYPT._-_Shaduf_(n.d.)_-_front_-_TIMEA.jpg

B. Livadas & Coutsicos, CC-BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

On another occasion Myrtle told her mother: “we went along narrow tracks between fields of clover, beans, lentils etc. Sometimes our way was along canal banks & under the mimosa trees, we often had to bend very low to avoid the branches, the scent was glorious … it is very pleasant to be riding along the country ways of Egypt …, far better than hooting along the dusty dirt roads in cars”. These canals could present something of a challenge when driving. In April 1932 Myrtle described a hurried round trip in “Joey” between the camp and Baliana, explaining that “of course European motorists would say 40 miles an hour is mere crawling – but let them try it on a narrow mud bank with a 15 ft drop to a canal on either side & scatter the track with a few goats, camels, donkeys, geese etc & I think they’d find all the thrills they wanted”. She confessed that she was not anxious to repeat the experience.

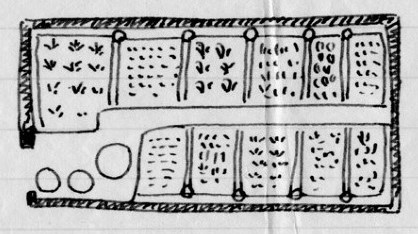

Myrtle’s letters often mentioned the dig house garden. This was carefully tended by Nannie, the Syrian housekeeper, and produced both flowers and vegetables. In an early letter to her father, Myrtle described the irrigation system, telling him that “it takes a man several hours a day to bring the water for [the gardens]. They are laid out with a perfect irrigation system … & are enclosed in mud walls about 14” high to keep out the sand. At the end of each little channel is a bit of pottery, the water is poured on this & flows all along the edges of the little beds”.

The dig house had its own well, though this occasionally gave trouble. In April 1932 Myrtle told her mother: “we have had to have the pipe men in to see to it [the well]. He has replaced three lengths of pipe, I drove Sardic in to Baliana to get the required pipes & special tools for the job, & we thought all was well – with the well – but today they found a special washer needed replacing, so I had to drive Sardic in again … to get these washers …. Sardic is … the only one who could be relied upon to get the proper washers for the pump”. Problems recurred in December 1934 when they had to have the pipe man back to attend to the well again. Myrtle reported that “the pipes were eaten through in parts so that the pump did not draw the water up, so we had to have 3 new lengths & the man was here all day fixing them”. This time she resourcefully supplied the leather needed for washers from the remains of an old boot left by former team member Charles Little.

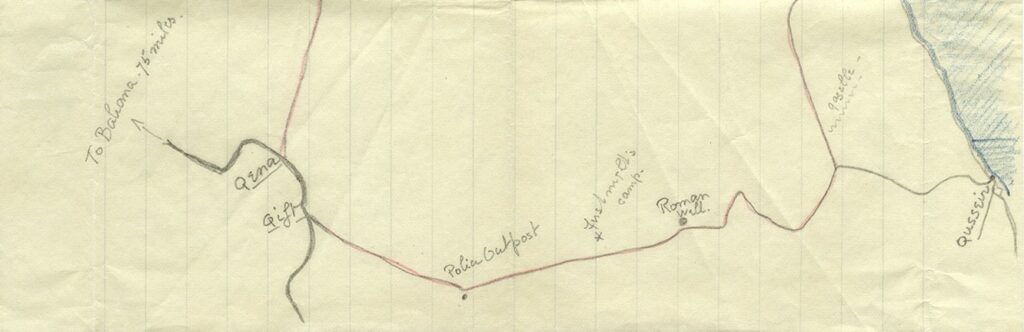

Given the importance of water, it is no surprise that Myrtle’s letters often mention other wells. At the end of their third season, Amice and Myrtle made a brief trip to Quseir on the Red Sea coast. En route they camped for one night in the desert near a well, but had no opportunity to explore it properly. Four years later, during a longer trip to the Red Sea in March 1936, they had time to do so. Myrtle told her mother that on the second day of their drive across the Eastern Desert, “we came to the old Roman Well that we had seen before but had no time to examine. This time we explored it thoroughly & climbed down the circular staircase that runs all round it till we reached the water level. The water was quite clean & warmish. It looked so strange to look up the shaft of the well & see Sardic looking down at us, we seemed such a long way down. & we were both very much out of breath when we reached the top”.

Letter 371, page 6

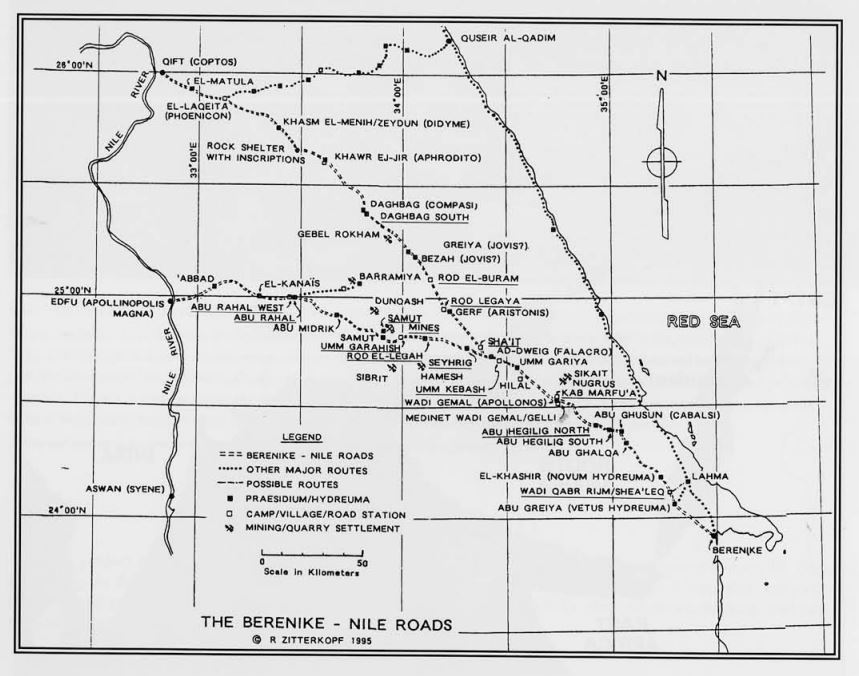

This was presumably a hydreuma or “watering station”, like the eight along the trade route from Qift to Berenice further south on the Red Sea coast which were described by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History. Hydreumata were of varying sizes; Pliny described one as large enough to provide accommodation for 2,000 travellers, and sometimes fortified and garrisoned. Their exact location along the route depended on the availability of water but they seem to have been spaced approximately a day’s travel apart, the mileage between stations varying with the difficulty of the terrain.

Map prepared by Ronald E. Zitterkopf for “Routes through the Eastern Desert of Egypt”, University of Pennsylvania Museum Expedition 37/2 (1995), fig. 2

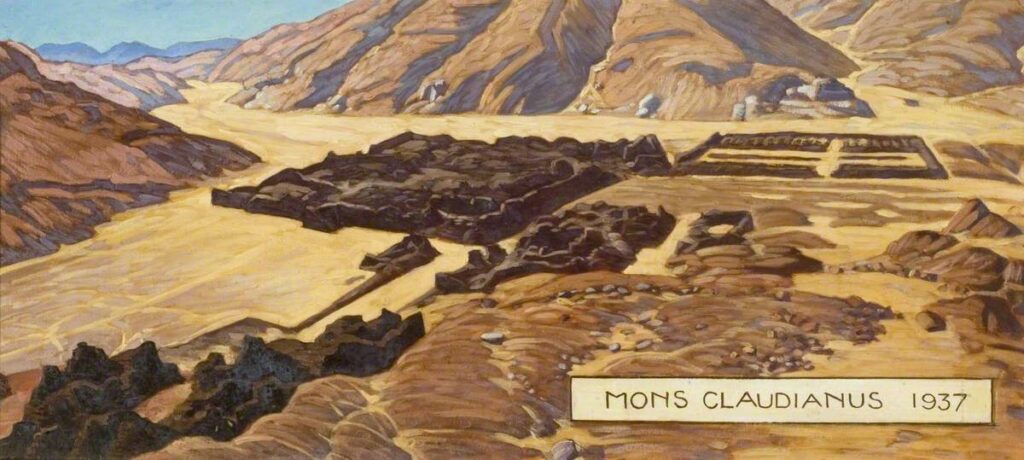

The following year Amice and Myrtle took another holiday on the Red Sea coast and explored other early water management systems. From their base at the marine research station in Hurghada, they made a day trip to the Roman quarries in the porphyry mountains, where they “examined the ruins of the settlement [made by] the Romans … who were in charge of the prisoners who worked in the quarries. We saw first of all the ruins of a reservoir where they stored the water, with pipes & conduits to carry it to the troughs where the animals were watered”. Two months later, at the start of their long drive back to the United Kingdom, they made a two-day excursion to Mons Claudianus, where “there was quite a town … in Roman times & quite a number of the houses are standing with most walls intact, some even roofed with great stone slabs. There were the baths still with cemented sides & steps leading down & the places for building fires to heat them, there were even niches in some of the walls for statues or busts”.

© Myrtle Broome (1937)

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Water supplies were similarly important when crossing the Western Desert. In February 1930 Amice and Myrtle, accompanied by Sardic together with a guide, other servants, and guards, went by camel to Kharga, a four-day journey. On the second day of their trek they passed through a place covered with broken pots. They “examined the area carefully & came to the conclusion it had been a Roman camp & that [their] camel track was really the remains of an ancient Roman road from the Oases to the Nile Valley & that they probably had water dumps at regular intervals & always near some outstanding rock or mound”. In 1935 Myrtle and Sardic returned to the Kharga and Dakhla Oases. This time they travelled by train, and Myrtle told her mother: “the train stopped every 40 kilo[metre]s or so to take in water from tanks by the rail (I suppose a water wagon goes along & fills these up the day before the train goes)”. Whatever the mode of transport, travellers still needed regularly spaced water supplies.

Sources:

Letters: 35, 47, 52, 64, 79, 98, 189, 191, 304, 329, 371, 382, 402, 409.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for Myrtle Broome’s painting

- the Mary Evans Picture Library, for the photograph of King Fouad opening the Nag Hammadi Barrage

- Ellison, A. R., “The Nag Hammadi Barrage, Upper Egypt”, Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers 232 (1931), 340–364

- Project Gutenberg, for the translation by John Bostock and Henry T. Riley of Pliny the Elder’s Natural History

- Sidebotham, S. E. and Zitterkopf, R. E., “Routes through the Eastern Desert of Egypt”, Philadelphia PA University of Pennsylvania Museum Expedition 37/2 (1995), 39–52; and Murray, G. W., “The Roman Roads and Stations in the Eastern Desert of Egypt”, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 11 (1925), 138–150, for information about hydreumata in the Eastern Desert