Animals – 8: Camels – 1: Learning to ride a camel

Author: Susan Biddle.

Myrtle Broome’s love of animals shines through many of her letters. This post is one of a series looking at the animals she encountered, and describes how she and the other members of the team learnt to ride camels.

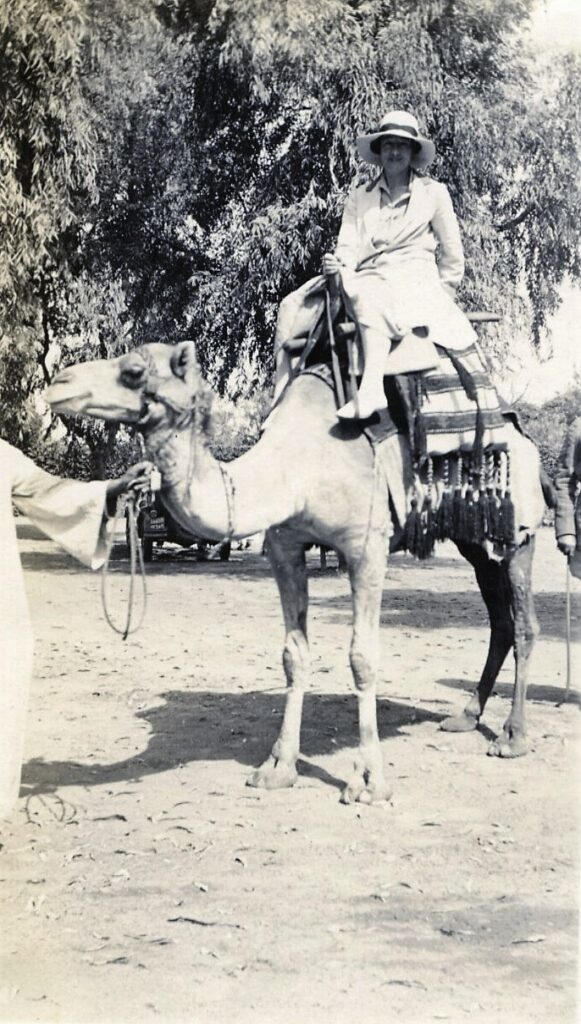

Myrtle was a keen horsewoman in England and enjoyed occasional rides on Arab horses in Egypt, but these were rare pleasures. There were far more camels than horses, and it was not long before she tried riding a camel. On 25 October 1929, a fortnight after first arriving at Abydos, she started her letter home: “I have had the thrill of thrills to-day. I rode on a real desert camel”. When camels brought their luggage from Baliana station to the camp a few days earlier, Myrtle had delighted the man in charge of the camels by taking a photograph of them. On 25 October more stores arrived the same way, and Myrtle told her mother: “the camels were unloaded just when we were ready to start for the temple, so the camel man asked me if I would like to ride his camel. You may be sure I did not say no. So the gaudiest blankets in the house were fetched and draped over the saddles and then I mounted one camel & Miss C. [Amice Calverley] the other. The man made a hissing noise & the camel heaved up his behind, nearly shot me over his head, then up went his front legs & I thought I should slide over his tail. Then he set off with his long swinging stride”. She was delighted by the experience, telling her mother that “it was perfectly wonderful, the easy swinging motion, going up & down the sand hills without a sound, it was fine being able to view the desert from such a height”. She continued: “when the camel broke into a trot I really thought my spine would be jarred through my head, but I think I could soon adapt myself to the motion. The folding up of the camel for me to dismount was also rather alarming, but I am glad to say I managed everything without loss of dignity”.

Photograph by Hugh Calverley (1929)

Bushey Museum & Art Gallery

Myrtle did not have another opportunity to ride a camel until the following year. In January 1930 Amice and Myrtle were invited to visit Arthur Ellison, the chief engineer building a new dam at Nag Hammadi. Thinking that Nag Hammadi was about 11 miles from the dig house, they “decided it would be good fun to go on camels”. Unsurprisingly, as their camel riding experience was limited to the single short jaunt the previous October, their idea “was received with some amazement & a lot of doubt as to our riding capabilities”. However Sardic, the head servant, was confident he could hire good camels and, despite finding that the distance was in fact 22 miles, they resolved to go ahead. Sardic was instructed to hire four camels, one each for Myrtle, Amice, and Captain Hugh Calverley, Amice’s brother who was responsible for photography and the generator, and a fourth to be shared between Sardic and the owner of the camels.

The four camels arrived by 6 a.m. on the day of the trip; blankets were spread over the saddles, which were pack saddles rather than riding ones, and Myrtle and Amice mounted. Myrtle told her mother: “Capt C. was a few minutes late … he came out with a rush, gave a wild yell & charged his kneeling camel intending to leap onto the saddle. The poor camel wasn’t used to this behaviour & shot straight up in terror. The Capt managed to clutch the poles of the saddle & was lifted off his feet clinging to them. For the moment the men were too helpless with laughter to render any assistance but finally he was hoisted up on top. I think it was the funniest thing I have ever seen”.

Imagery © 2025 Airbus, Maxar Technologies, Map data © 2025, Map data © Google

The first part of their journey was across desert, and once again Mrytle found it “a gorgeous feeling to be mounted on a great tall beast going along with swinging strides”. After a few miles they turned into the cultivated area, passing “along narrow tracks between fields of clover, beans, lentils etc … along canal banks & under the mimosa trees … the scent was glorious”. Myrtle explained that “often we stopped to talk to the people & ask them about their crops, & we were given handfuls of flowering beans & clover”. Fortunately they “did not have to carry these far, for soon an inquiring nose came round & the camel begged for a mouthful”. Sometimes they met another party of camels going in the same direction, and they “would all jog along merrily, enquiring after each other’s health & where from & where going”. She told her mother: “it is very pleasant to be riding along the country ways of Egypt in the proper native style, far better than hooting along the dusty dirt roads in cars, being cursed by all the people … we were merely pleasant & interested, & we received courteous greetings & blessings & handfuls of flowers”.

By 12.30 p.m. they were within sight of their destination, so paused for a picnic lunch on the banks of the Nile. After all their exertions, they no doubt felt they deserved their “bully beef, tomatoes, baked potatoes & bread, a tin of peaches, cake, biscuits & oranges”. Myrtle conceded that by this time “we were getting very stiff & saddle sore. We had done nearly 20 miles in one stretch, part walking, part trotting. A camel’s trot is the most ghastly motion one can imagine at first, one feels as if one’s spine is being jarred through one’s head, after a while one finds the best way is to let one’s body go limp & sway to the motion”. After lunch and a brief rest they re-mounted and completed their journey to the Ellisons’ house. Myrtle told her mother that “Mr & Mrs Ellison were delighted to see us, but held up their hands in horror when they heard we had come all the way by camel in 6 ½ hours. They said such a ride was considered very good going for the camel corps … & they would not believe we had only been on a camel once before for a quarter of an hour”. They admitted to “being very stiff & sore” and, after visiting the Nile barrage, Amice and Myrtle “each had a glorious hot bath with vinegar in it & doctored each other’s sore patches with cold cream”. They had “a very cheery dinner” with the Ellisons; Amice and Myrtle dressed in frocks and shoes lent by Mrs Ellison so they could get out of their breeches and boots for a while. They returned to Arabah el-Madfunah in the Ellisons’ car, the camel man having started back with his four camels as soon as the animals were fed and rested. Myrtle told her mother that they reached the dig house at 10.30 p.m. “so tired, but so very pleased with ourselves”. Determined to confound the many who had said they would never get as far as Nag Hammadi, particularly as they were riding the less comfortable pack camels, Myrtle and Amice were “up [the next] morning by 6.30 & at work as usual, none the worse for our adventure (though still a little stiff & sore as to seat & back)”.

A couple of days later, flushed with the success of their Nag Hammadi trip, they planned a three-day camel ride 120 miles across the Western Desert to the Kharga Oasis for their leave in February. Hugh Calverley passed up this opportunity, Myrtle confiding to her mother that “he doesn’t enjoy camel riding. It makes him feel sea-sick & he thinks we are perfectly mad to think of such a trip. He teases us about it tremendously”. Myrtle and Amice were, however, made of sterner stuff. They duly made their trek in mid-February together with a friend of Amice and escorted by Sardic, a guide, and seven camel men – the first of many camel treks Myrtle was to make during her leaves in the next seven years.

Sources:

Letters:

34, 52, 53, 60, 64.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for Myrtle Broome’s photographs

- Google Maps, for the map showing the journey from Baliana to Nag Hammadi