Shoes and clothes – 2

Author: Susan Biddle.

This post is the second in a series looking at clothing. This instalment focuses on footwear.

The team’s shoes and boots got hard wear in Abydos. Just two months after arriving in Egypt for her first season, in January 1930, Myrtle wrote to her mother to say her canvas shoes were now “quite useless, the sole has come right away from the upper”. She thought that an English bootmaker could probably have mended them, as the sole and upper were in good condition, and it was only the stitching that had gone. However she did not think it was worth asking the Egyptian cobbler to mend them as “he does not understand how our boots are constructed”. Instead she asked her mother to order new boots for her from Gamages, a well-known London department store. She expected to receive these new boots within three to four weeks. In the meantime she was reduced to “wearing rubber shoes & stockings”, reassuring her mother that “it is quite safe to wear shoes now as all the snakes have gone to sleep in their holes for winter”. Myrtle’s confidence may have been misplaced; in January 1932 she told her mother that she and Amice were “glad we were wearing high boots” when one of the guards brought them – still alive – a small horned viper he had caught. By the seventh season Myrtle was repairing her own shoes, telling her mother in December 1935: “I have been repairing my rubber soled shoes with Rhino Sole, a solution I got in a tube in Woolworths, it is very successful”.

For the second season, Myrtle had boots with zip fasteners. They very much impressed the head servant, Sardic, who “politely enquired if they cost a great deal of money”. It was not only Sardic who was intrigued by the zip fasteners. In March 1931 Myrtle removed her boots when visiting the tomb of Sheikh Ali, a holy man, and noted that “the zip fasteners caused great astonishment”. Returning from the tomb, she visited Sardic’s sister-in-law, and told her mother that “when I got stumped for conversation I showed them how my boots worked – that was a very popular move”. The modern zip had only been designed in 1913 and patented four years later under the name of “separable fastener” by a Swedish-American, Gideon Sundback. The term “zipper” was not used until 1922, by another company who included Sundback’s device on their rubber overboots which they marketed as “zippers”. It was therefore not surprising that the Egyptians should be intrigued by what was still in 1931 a relatively new invention.

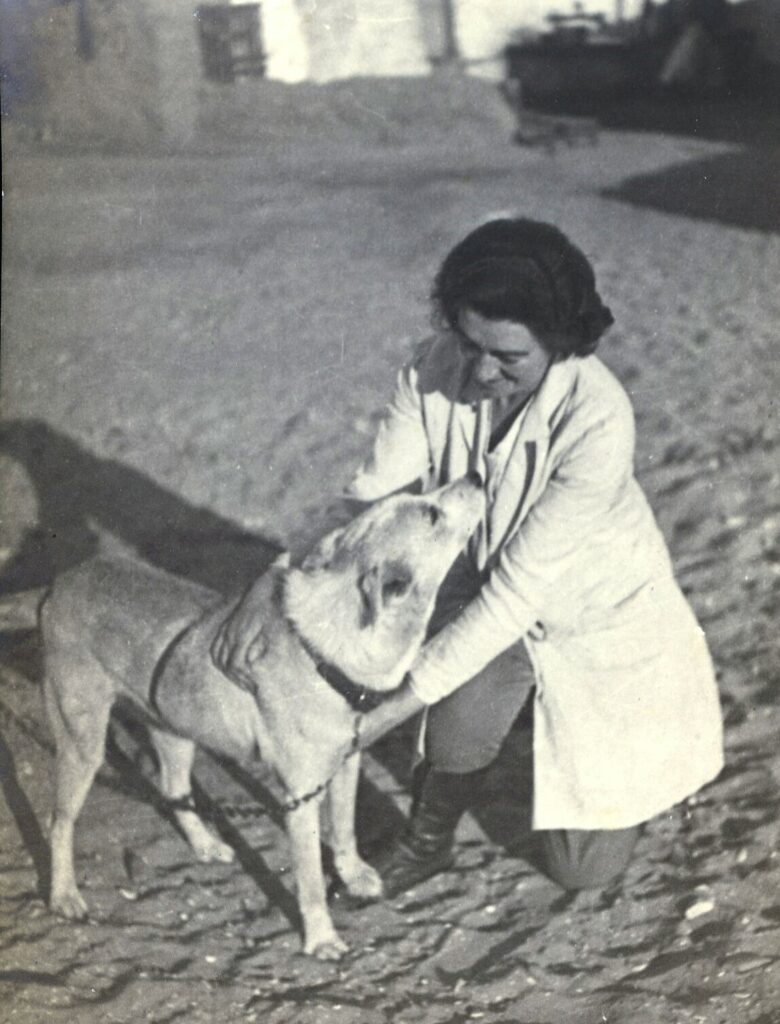

Photograph by Amice Calverley (date not known)

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Myrtle also had “nice riding boots”, but kept these for “swell occasions”. Sardic’s many jobs included polishing the boots with a polisher sent from Myrtle’s father.

Like Myrtle, Amice wore a mixture of shoes and boots, keeping them in a box brought from England packed with apples and pears from the orchard at Avalon, Myrtle’s home in Hertfordshire. Some of Amice’s shoes do not look as though they would have provided any protection from snakes.

Photograph by Myrtle Broome (1934)

Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Worn-out footwear was recycled in various ways. In November 1933 Myrtle and a fellow artist, Charles Little (known to the team as “Little ‘Un’”), were intrigued by the leatherwork done by Mohammed Kheir, one of the three Sudanese soldiers who guarded the camp. Myrtle told her mother: “I have been cutting up my ancient boots & making long strips of the leather & binding a palm stick with it, as Mahommed Kheir showed me, to make a riding whip”. In November the following year she made one of the camp dogs “a hand sewn leather collar that was once part of the leg of a boot”. A month later water pipes for the camp were eaten through in parts so the pump did not draw the water up, requiring three new lengths of pipe. Myrtle explained to her mother that “Sardic came to me to request strips of leather for washers which were supplied by the remains of Little Un’s last boot”. On another occasion a boot was cut up in more gory circumstances – when Otto Daum, another artist in the team, had an accident in the Temple of Seti, Myrtle found him with “his boot covered with blood & the ankle bone sticking out over the top of his boot. With the men’s help I got him on a chair, cut his boot off, set the bone in place as best I could & bound a slat from a drawing board as a splint”. More cheerfully, in February 1936 Amice and Myrtle had a brief holiday on the Red Sea coast, taking with them “old shoes to paddle in on the coral reef”.

During her time in Egypt Myrtle learnt to appreciate the talents of the Egyptian cobblers. In December 1930 one of the servants, Ahmud, showed Myrtle “a pair of new shoes he has had made. They are wonderful. The soles are gamoose [water-buffalo] hide & they are all sewn together with thongs in the most ingenious way; a man in the village made them”. She described them as “this shape [with a small sketch] not like the others with no heels. They are rather stiff but very light & can only be got from a little village cobbler”.

Myrtle was so taken with them that she wanted to have a pair made for her father, and asked her mother to send her a paper sole in her father’s size. She thought she might also have a second pair made for Eric, a friend back in England. By 23 January 1931 the paper sole pattern had arrived in Egypt, and Sardic had taken it to the village cobbler. Myrtle hoped that the cobbler “will not try to imitate European shoes, I very definitely said they were to be exactly like Ahmud’s only as long as the paper sole”. In early March Myrtle reported to her father that “Sardic has brought home your shoes. I have had two pairs made, you are to choose which you like best, & Eric is to have the other pair. I don’t know if you will be able to wear them, as they are stiff and have turn up toes specially for walking in sand. They are made of buffalo hide, rough workmanship but very cleverly constructed, all sewn together with thongs of hide. Ahmud says he has worn a pair out here in the sand continually for two years, so I thought they would be amusing to have as specimens of native work”. Her father, Washington Herbert Broome, was no doubt interested in such examples of indigenous craftsmanship, as he was himself a designer and craftsman of the Arts and Crafts movement.

Later in the same month Myrtle bought her father “another sort of slipper & also a pair for myself”. She explained to her father: “I have bought you such a posh pair of shoes, a nice cheerful orange, they are the same as Sardic wears & considered very superior”; they were “not so funny as the others & I expect [you] will be able to really wear these”.She was going to make the three pairs of shoes (the two pairs made like Ahmud’s shoes plus the third pair like Sardic’s) into one parcel, telling her father again: “You are to choose which pair of the gamoose hide shoes you like best, & the other pair are for Eric, one pair is red the other black. I don’t know which you will prefer. I do hope the orange goatskin shoes will fit you as I think they will make you comfy house shoes & they are stout enough for garden wear also. If the gamoose hide shoes pinch your toes you might lend them to Mrs Childs [who seems to have worked for the Broomes] for washing days”. Myrtle’s own pair was also orange, and she wore them around the dig house, reporting them “quite comfy”. Sending off the parcel required “umpteen forms”, but by the end of April the shoes had arrived in England, and Mrytle was “so glad to hear the shoes arrived safely & have given so much pleasure & amusement”.

Photograph by Susan Biddle (2023)

Pitt Rivers Museum, inv. no. 1928.45.20

Sources:

Letters: 53, 101, 102, 108, 123, 125, 126, 129, 131, 134, 161, 243, 245, 300, 304, 357, 359, 370, 382.

With thanks to:

- the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford, for the opportunity to work on the Broome collection, and for their ongoing support for this blog

- the Bushey Museum and Art Gallery, for Myrtle Broome’s photographs

- the Pitt Rivers Museum, for the information about goatskin slippers

- Green, Cynthia, How WWI made the zipper a success, JSTOR Daily (2018), and Bellis, Mary, The History of the Zipper, ThoughtCo (2019), for information about the invention of zip fasteners

- the Victoria & Albert Museum, for the link to the Arts and Crafts movement